Chapter 4: What Is a Story, and How Does it Work?

What Is a Story, and How Does it Work?

Can you define the term story?

You've seen thousands of them on television and in movies. You've probably heard them from the time that you were a toddler on your mother's lap, and you may hear more of them while standing in line at a water cooler at work.

In fact, you've seen so many of them that you recognize them without thinking about their integral parts. They're like ants that way. You spot a bug on the ground down at your feet; it's plodding along with a bit of a leaf, and you go "Ah, an ant!" But you don't have to fall down on your face and peer at it, count its legs and antennae, and ponder for long in order to recognize that this is indeed an ant and not some other vermin with a similar exoskeleton. You know instantly that it's an ant, not a beetle posing as one.

You've seen and heard so many stories that, in fact, you don't just recognize them, you subconsciously judge them.

As you're watching a movie, you evaluate how the story stacks up to all others. If you feel something amiss, you might even begin to critique it consciously. "Ah," you might tell yourself, "this just doesn't work as a romance. The male lead is too creepy. I really want the girl to run away from him, not fall into his arms."

If, in the end, the writer fails to even create a story, you'll know. You might say, "The hero saved the girl way too easily," or "I just didn't feel anything at the end."

So you know a story when you see it.

But what makes a story? What makes a great tale powerful? Why do we care about stories? Why do people want to read them instead of playing video games?

The answers to these questions aren't easy to come by. Many people have tried to define what makes a story—Aristotle, Feralt, Emerson, Budrys, and dozens of others.

The Scope of the Problem

Most people who try to define what a story is are secretly more interested in another question: what makes a great story powerful?

Thus, Aristotle began to define a story in those terms. He reasoned that a great story has a sympathetic hero with a powerful conflict, and as the story progresses, it has a "rising action" which arouses passion in the viewer until the problem is resolved and we either feel elation that the hero has won, or we pity his fallen state.

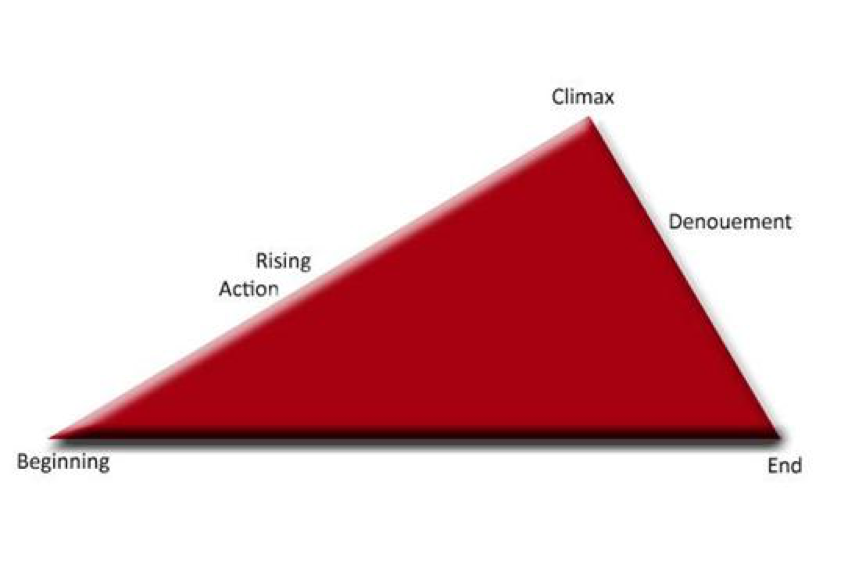

Feralt's Triangle

Feralt said that in a successful story, the tale begins with a character in a relaxed state, but soon a problem is introduced. As we progress through the tale, the suspense rises, the problem becomes more complex and has more far-reaching consequences, until we reach the climax of the story, where the hero's fortune changes—either he resolved the problem, is destroyed, or must learn to live with the problem. In any case, the tension diminishes, and the reader is allowed to return to a relaxed state.

That triangle describes most commercial fiction of the 1800s, and indeed describes most of the genre fiction, television, and movies today.

But then the 1900s came along, and a number of authors began to reject "formed" fiction. In part they were reacting to the fact that so many of the genres had reached a point where plots had become so rigid that the outcomes of the stories were predictable.

In short, they were looking for new and exciting ways to form stories. In some cases, authors began to write non-formed fiction altogether. Some writers, the social Darwinists, even reached the conclusion that "since there is no god, and life itself is just a random series of events, it makes no sense to try to make sense of life through our fiction. Thus, to create a formed story, one that seeks to reach some kind of logical conclusion, is in fact to perpetuate a lie."

So in the early 1900s we began to get the "slice of life" stories and vignettes by such fine writers as Virginia Wolfe. The point wasn't to tell a formed story, but simply to capture a fascinating moment in a character's life—perhaps a conversation, or a spring day.

Other writers recognized that readers had developed such a solid sense of story that the reader often filled in the gaps himself when reading. In short, there is a subconscious collaboration between the author and the audience. Thus, Ernest Hemingway wrote a story once and sent it to his agent. He penned a note with it that said, "I wrote a story about a man who receives a telegram telling him that his son has died in the war. Then he goes to a bar and gets drunk. Afterward, he goes home and hangs himself. But I cut off the beginning and the end. I think that the one scene is enough—they'll get the rest from the tone." His short story, "A Clean, Well-lighted Place," is one of Hemingway's most celebrated and can be found in a number of short story collections.

With some people rejecting form completely and other writers truncating their stories and purposely omitting parts of the tale—the ending in particular—or otherwise making the tale obscure, it soon became difficult for a critic to define what a story is.

After all, if we define it too rigidly, we take the risk that new authors will become slavish in their imitations of past works, and thus will not experiment with new forms.

Given this, some critics of the 1940s and beyond will glibly tell you, "A story is anything that the author says that it is." But such a broad description merely infuriates a new writer who can't figure out why his plot doesn't seem to be working.

So, let's take the bones of a story and see if we can figure out just when it becomes a story in form. Let's take a true piece of trivia:

In the town where I grew up, there lived a man who kept three pet lions in his house—until they ate him.

By the broadest definition of what a story is, that's a story. It's written on paper, I'm a New York Times bestselling author, and if I say it's a story, it's a story.

But you as the reader of course recognize that it isn't a story. It has too many gaping holes. "Really?" you might ask. "Did this really happen? Why would anyone keep lions in their house? Where did this happen and when? Why did the lions eat him? What really happened?"

So let's try a longer version:

In the town that I lived, Monroe, Oregon, we had a man who kept three lions in his house. This was back in 1979. My father owned a meat company, and every day or two, the man, Paul, would load his pet lions into the back of his pickup and bring them to our store.

He would buy steaks, beef bones, and bags of dog food to feed to his lions. I actually went out and petted them on several occasions, and the sight of them always thrilled the out-of-town customers.

Paul was quite wealthy. He built a huge house with a sunken living room, and catwalks along the upper levels gave his lions a nice place to perch while he sat on his bean bags and watched television.

In fact, he bought the lions from a good friend of mine, a fellow named Jack Lawrence, who sold exotic pets. Jack used to keep an ostrich in his house in a bird cage, and he always had a couple of Bengal tigers out in his barns, along with lions and bears, and a huge white buffalo. It turns out that not many people want lions, and so you could buy one back then for about five hundred dollars.

Then Paul's lions ate him.

So we've got a longer version. You might see that in this one, I've answered some objections. I gave you more of a setting—a time and place—and I even went so far as to let you know where the lions came from, thus making the tale more plausible.

But this isn't a story yet, is it? At the best, it's merely an incident or an event.

Ronald Tobias's book, 20 Master Plots, contains a good discussion of story as told from the point of view of a mainstream scholar. He comes close to getting a definition, and reaches the conclusion that a story is "a series of causally related events."

He reaches his conclusion thus: Somerset Maugham once said that unrelated events were not a story, but causally related events were. Maugham provided the example: "The king died, and then the queen died."

Those are mere occurrences, not a story. We get no satisfaction from them. Indeed, we don't really care.

But imagine if you said, "The king died, and then the queen died of grief."

Maugham suggested that that was a story, and Tobias agrees. The causal relationship creates something of a story. It has a beginning, implies a middle, and it ends. The tale answers the question "Why?"

But it's not really a story, is it? If it were, our jobs would be so much easier. Here's a short story written by his definition: The chicken crossed the road, got hungry from its journey, and caught a caterpillar to eat.

Obviously, that doesn't stack up well against Hamlet, or even Harry Potter.

The caterpillar story will never sell, nor will the queen's death. The problem is that Tobias hasn't paid attention to what stories do: they simultaneously try to make sense of the world and entertain. His example makes sense of the world, but does not entertain. He has only a part of the equation.

Here is a little better definition: a story is a series of causally related events and actions that are meant to entertain and that answer an important question: "Why?"

You see by the italics what I have added.

Let's go back to the lion story. Why did the lions eat this fellow? Everyone knows that African lions don't make good pets. Why have them in the first place?

Let me carry the tale a bit further:

In the town that I lived, Monroe, Oregon, we had a man named Paul who kept three lions in his house. This was back in 1979. My father owned a meat company, and every day or two, Paul would load his pet lions into the back of his pickup and bring them to our store. There he would buy steaks, beef bones, and bags of dog food to feed to his lions. I actually went out and petted the lions on several occasions, and it always thrilled the out-of-town customers.

Paul was quite wealthy. He built a huge house with a sunken living room, and catwalks along the upper levels gave his lions a nice place to perch while he sat on his bean bags and watched television.

In fact, he bought the lions from a good friend of mine, a fellow named Jack Lawrence, who sold exotic animals as pets and to zoos. Jack used to keep an ostrich in his house in a bird cage, and he always had a couple of Bengal tigers out in his barns, along with a few lions and bears, and even a white buffalo. It turns out that not many people want lions, and so you could buy one back then for about five hundred dollars.

I once asked Paul why he had bought the lions. He told me that he liked the novelty of it. But there were darker rumors in town. Paul had a lot of money, but no job. Folks whispered that he was a drug dealer. He kept the lions, it was said, much in the way that other people keep pit bulls—to keep people away from his house.

I believed the rumors. Paul had an oily look to him, much like a Hollywood movie producer, and he was always anxious, always peering over his shoulder, his eyes darting about.

He had a beautiful wife. Both of them were in their mid-20s, but apparently there were real problems in their marriage. The neighbors complained of screaming fights and bickering.

So the day that Paul got eaten, here is what happened:

He and his wife got in a brawl. No one knows what the fight was about, but the town had its suspicions. There had been reports of gunmen sneaking up on the house two nights before, and Paul had kept his wife locked in for days.

It was said that she wanted him to leave, to take their drugs and money and head to Hawaii.

After the fight, she left the house crying and told Paul that she didn't want to live like that anymore. Then she drove a hundred miles to her parents' house and stayed there for three days.

As she left, Paul yelled at her back, "Yeah, well I'm leaving you! You can keep the damned house!"

As she raced off in her sports car, he leapt into his pickup and sent dirt flying as he sped away.

She refused to call him for the next two days, and he didn't call her.

But she worried about the lions. Had they been fed? African lions are calm when they are well fed, but they get nasty when they're hungry. So she worried.

On Sunday morning, the third day out, she finally called the house. No one picked up. She phoned one of her husband's drug-dealing friends and asked if he had seen Paul. The dealer replied that Paul had stayed at his house until late Saturday night, and then had gone home to feed the lions, but had not returned.

Shaking with trepidation, she drove home and found Paul's pickup outside. She rang the bell, but no one answered. So she carefully entered the house.

She flipped on the lights to the living room and immediately spotted a huge bloodstain on the tan carpet in front of the television. In the center of the bloodstain was all that was left of Paul—the upper half of his skull.

There was speculation that drug dealers had killed Paul, and for a couple of days we wondered.

The police disposed of the lions. They cut the cats open to retrieve enough of Paul's lower skull to check his dental records. It was him. The rest of his body—flesh, hair, hide and bones—were all found inside the lions, too.

There were no signs of foul play—no bullets riddling the body.

Only an idiot would keep lions in his house.

Now, as stories go, this doesn't compare to Gone with the Wind. But it does have more of the bare elements of a story. The characters, Paul and his wife (names have been changed to protect the innocent), are brought into the story. They are assigned motives for their actions, motives that might be exaggerated or completely untrue. A problem develops. Both parties become concerned for the lions and return to feed them, hoping to resolve the problem, and one of the two parties is eaten. The story is resolved, of course, only when the lions are destroyed.

This story even has a moral: don't keep lions in your house.

It's obvious why the events within a story need to entertain. After all, you want people to pay you money to make this stuff up!

But it is less obvious why I've added the phrase "The tale answers the question 'Why?'" when I defined a story.

Do stories really need to justify their own existence? Or can we write successful tales that only pose questions?

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top