37. Of Plots and Plugs

After Charles had finished his address and dismissed the crew, I fetched the pannier and went forward to the cookery. Back in the great cabin, when I greeted Steward with it filled, I sensed no change in his manner, and while he arranged our suppers onto the porcelain plates, nothing indicated he had seen the details of my nethers. Or if he had, it appears he had not recognised the difference.

I breathed quiet sighs of relief while I took my seat at the table, and more sighs upon observing that his service was as always – respectful, efficient and silent. Silent but for the customary wish of good health before he left for the gunrooms. When I heard the door close, I said to Charles, "I do not think he had seen any details."

"Possibly not. But he is a quiet man who expresses few thoughts." Charles laughed. "And I am delighted by this. If he were more loquacious, more expressive, he would have filled my need for intercourse, and I would not have discovered the wonder of you."

"Oh, but you would have." I giggled. "I would simply have had to work harder to cause it."

Charles chuckled as he placed a hand on mine. "I do love your confidence."

"So, tell me about the route onward from here."

"It would be easier for me to show you while I plot it on the chart." He pointed to our plates. "Let us finish supping first. What are your thoughts on the attitude of the crew about nautical myths?"

"It pleases me that some seem to dispute them, rather than to believe." I chuckled. "I had not before heard the one about redheads. Did Mid Edwards invent that as a hiccus doctius to scoff me? To scoff us? He seems full of jest."

"No, that is one of the old tales, and from whence it comes, I know not. But being more red than brown myself, I dismissed it when first I heard it told."

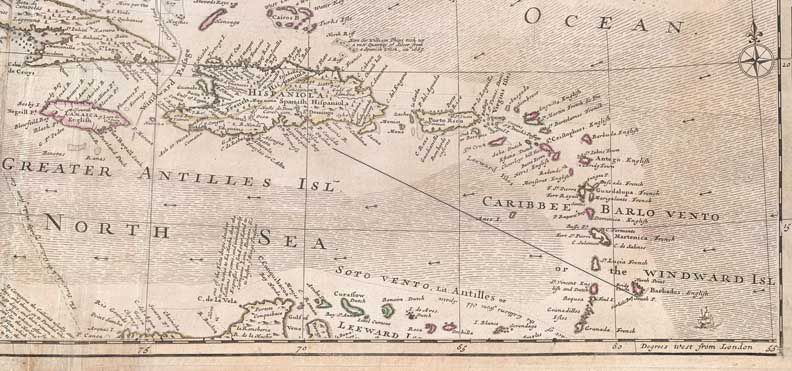

When we had finished eating, Charles took me across the cabin to the chart table, where he lit the candles and pulled a large sheet from the drawer, unfolded and spread it out. Then with a pencil, he ruled a line from Barbados, passing between two small islands. "This is the route we will endeavour to make during the first few days."

I followed the plotted line with my eyes, and in the flicker of candlelight, I tried to read the small printing at its end. "Is this where Port Royal is?"

"No, it is much farther west." He tapped the chart. "Over here. But following this line will add safety to our navigation."

He laid a round brass piece on the chart, and as he moved it, he explained, "We centre our position in the hole of the protractor, then align North with the closest meridian and —"

"Why are the meridians at different angles, not parallel?"

"Think of an orange with its curved segments. They all converge at top and bottom, and with the earth, this is at the poles."

I nodded as he explained. "Yes, of course. Father had told me this, but I had forgotten."

Charles pointed to the letters at the rim of the device. "This shows our route is west-northwest, half north, and it will allow us to middle the water between Saint Vincent and Santa Lucia , then we will continue along this track for about six hundred miles. It should take two and a half to three days for us to arrive at latitude seventeen twenty-five."

"Aha! To the latitude of the southern point of Hispaniola."

"No, not to it. About five miles south of it, so that we miss it in passing, but close enough that we can see it and fix our longitude as we sail past," He ruled another line across the chart to the island named Jamaica. "This is only twenty-five miles south of the latitude of the entrance to Port Royal, and our practice is to remain within sight of Hispaniola to know our progress westward."

I looked at the length of the second line and compared it to the first. "So, two days or less from there."

"With fine conditions and fair winds, yes. Usually less than five days to Port Royal from here."

"And in adverse?"

"It depends upon how adverse." He set the pencil on the chart and pulled me into an embrace. "There are often severe storms in the summer and early autumn, but winter and spring weather is generally benign. This evening's sun showed it continuing fine."

I rose to my toes and tilted my head up to receive his kiss.

Friday, 18th December 1676

After breakfast on Friday morning, I accompanied Charles ashore as he headed to call on the rumbullion agent to confirm the quantity and the timing of its loading. He left me at Mistress Duncan's millinery, where I purchased four yards of linen and five yards of brightly-patterned Calicut cotton, along with scissors to cut and needles and threads with which to sew.

When we returned aboard, Charles counted shillings and sixpence into piles on the table, explaining this was to pay for the purchased goods. When he was done, he sat at his desk copying details of the auction lots for Port Royal. Such tedious and exacting work, two copies of each of fifty-four pages, and I admired him for it.

All the while, I sat by the windows and hemmed the cut edges of the linen, slowly creating new towels for our bathing. As I did, I wondered where the tub is stowed; I had not seen it during all my cleaning.

Not a matter with which to disturb him, so I continued stitching, the occasional light pang in my belly, adding to my increasingly dour mood and reminding me it would soon be time. The last came a day after the full moon. This one is sooner.

I set down my work, rose and crossed the cabin to the privy, then relieved to see no colour, I took another cotton square from the box, and with the bundle of twine, returned to my chair. After studying the size for a while, and picturing Ruth's instructions in my mind, I cut the piece into three strips, stacked them and cut twice more, making nine smaller squares. These I stacked and folded once, and with a loop of twine, seized them about their middle.

As I held it up by the string to examine, Charles asked, "What is this you have made?"

"Ruth calls it a mouse."

"Aye, and you have it by its tail. Next, snip and trim the body to make a better resemblance."

"This will serve perfectly as is."

"Serve? For what purpose? Is it more play she has taught you to have with me?"

I shook my head. "No, it will serve as a plug." I placed a hand on my belly. "My ache has begun. My monthly time nears."

Charles rose from the desk and strode across the cabin to me, asking as he approached, "How might I comfort you?"

"I have not ever been comforted with this, so I know not how you might." I shrugged. "That you know my condition is sufficient for now."

He nodded, then kneeling beside my chair, he leaned to kiss my forehead, my nose and then my lips as I tilted my head up.

After a wondrously passionate kiss, Charles returned to continue his copying, and I returned to the privy to insert the mouse, wanting to test its fit before making more of them. Much easier than stuffing a wad. I pulled the string, delighted with the ease of removal. Still no colour, but I reinserted it to be safe. Then I took another dozen squares back to my seat at the windows.

A long time later, after the mice were made and I had resumed hemming the towels, eight bells sounded. On my way forward with the pannier, a strange aroma caused me to pause and watch the lowering of a huge cask into the hold. I asked the older sailor standing nearby, the one who appeared to be in charge, "Is that the rumbullion which smells so sweet?"

"Aye, Boy, and that's near the last of 'em." He pointed to the waggon on the wharf. "Only three yet to load."

"And what with the water and provisions?"

"Them's all done now, but for the payin'." He indicated Mister Jenkins who was leading a gentleman toward the great cabin door. "And that's soon done."

"Then we sail?"

"That's for Captain to decide." He turned back to watch the handling of the cask. "But all else 'cept this seems about ready."

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top