Marital Problems

Much like her father, Queen Mary faced the problem of figuring out who would succeed her. Although she did not like being told what to do, she knew that marriage was as much her duty "as government and religion." [39] In order for her to even attempt to figure out who would ascend to the throne after her, she needed to first find a husband. Many names were proposed to her when she was a princess, but as Queen she had more of a say over whom she would wed. Yet, Charles V had a major influence on her decision. As a princess, Charles V was one of the potential husbands proposed for Mary. However, now at a much older age and battling a war with France and health issues, he decided that he was not fit to rekindle an old rumor. Working through his new ambassador to England, Simon Renard, Charles V suggested his own son, Prince Philip II of Spain, as a potential groom. Charles V instructed Renard to pass along a message to the Queen:

"If age and health had permitted, you would have desired no other match, but as years and infirmity rendered your person a poor thing to be offered to her, you could think of no one dearer to you or better suited than my lord the prince, your son, who was of middle age, of distinguished qualities and of honourable and Catholic upbringing." [40]

The reason for proposing his own son as a potential husband for Queen Mary was to "unite England with the Emperor's territories in a permanent alliance" through the royal marriage. [41] The Emperor got his way and on October 10, 1553, Simon Renard knelt before Queen Mary, offering her Prince Philip's hand in marriage.

That is when all hell broke loose.

Although it was possible for foreigners to rule different countries through a royal marriage, the general consensus was to avoid such marriages. Even if such marriages did occur, they generally included a woman princess or high lady being married off to a king in another court to establish an alliance between the two nations. But Queen Mary was different. Her title itself was revolutionary. Sure there were queens before her, but she was the first female ruling monarch of England. Everything with her would be different and revolutionary. As the sole ruler of England and as a woman, Queen Mary marrying another prince of foreign blood would make him the King of England. In this strongly patriarchal society, that would translate into this foreign prince ruling England; and no one believed that Philip would adhere to any restrictions placed on him (including barring him from English politics) once he became king. [42]

The idea of a foreign king ruling England angered many people. Not only was Queen Mary trying to reinstate the Catholic faith, she was betraying her country. Amongst the many people and leaders (including King Henry II of France) who protested this marriage, Thomas Wyatt had the loudest voice.

(Image of Sir Thomas Wyatt, whose name represents the rebellion to overthrow Mary.)

Wyatt was a soldier who served in France under King Henry VIII's wars against the French. He was also a gentleman of Kent, and was depicted as being the mastermind behind the rebellion that bears his name. Yet Thomas Wyatt claimed he was "only the fourth or fifth man" in the leadership for the rebellion against Queen Mary. [43] His plan was to ignite various small rebellions in the areas surrounding London before marching on London itself. He began by sparking a rebellion in Devon.

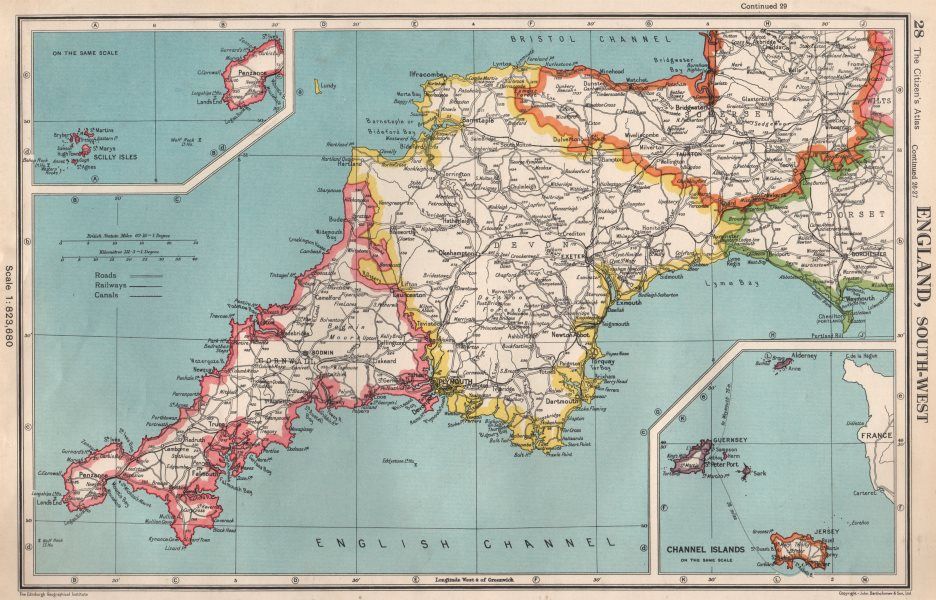

(Old map of Devon, located in Southwest England)

However, Wyatt's plan faced some roadblocks. For starters, he had included too many people in the conflict. There was no way to keep a secret. Eventually the Queen was bound to find out, and when she did she would begin to prepare her defense of the city of London. Secondly, the conspirators were nervous about betraying England with an alliance with the hated French, who supplied the rebellion with arms and funding. [44] Yet, the French did not immediately commit to the cause, and the conspirators disagreed over what they would do if the rebellion succeeded. Some people simply wanted Mary to abandon the marriage to Prince Philip, others wanted to dethrone Mary altogether and establish Elizabeth as Queen. Yet if the latter were to occur, they needed to supply Elizabeth with a husband. Edward Courtenay, the earl of Devonshire, was commonly put forward as a potential husband for the potential new queen.

Nevertheless, what Thomas Wyatt had done was to bring Queen Elizabeth into the fold. Now she would be mixed up in the rebellion and lose all of Queen Mary's trust. When the rebellion began on January 25, 1554, Queen Mary ordered Elizabeth to report to London. When Elizabeth refused to come to court on account of ill health, Mary regretted allowing her to leave London in the first place. On the day that Mary wrote to Elizabeth to return to court, a French spy was intercepted near Rochester, bearing a French translation of a letter Elizabeth wrote to Mary days ago. This incident had one of two possibilities. Either someone in her council was a traitor and was passing secrets onto the French, or Elizabeth had established a secret line of communication with the French. [45]

This was the perfect opportunity for Simon Renard, ambassador of Charles V to England, to swoop in and accuse Elizabeth of treachery. Simon disliked Elizabeth and had proposed on multiple occasions for Mary to get rid of her sister either by imprisonment or execution. However, Mary was a humble woman and did not wish to execute her half-sister, the same woman Queen Mary cared for when Elizabeth was just a baby. Yet while the rest of her councilors, Bishop Stephen Gardiner and William Paget, were blaming each other for the predicament Mary was in, Simon Renard was "the only person willing, almost eager, to tell her what he thought was going on." [46] Here we have exclusive evidence of the amount of an effect Charles V, through Simon Renard, had on Queen Mary during her reign. Although Mary was willing to disobey the advice of Renard before, she was now in a situation where she saw herself at fault because she had not listened to Simon Renard's advice, which was to take a tougher stand on the dissenting Protestants.

With Wyatt forming a large force near Rochester, England (east of London), Queen Mary ordered forces to confront Wyatt at Rochester. The forces were commanded by the duke of Norfolk; but disaster struck when most of the duke's men switched over to the enemy's side after most likely receiving financial incentives from Wyatt's colleague Antoine de Noailles. The duke retired the next day after having failed his Queen. [47]

The situation was looking desperate. Men who were supposed to be loyal to the Queen, were deserting the Queen in favor of open rebellion to dethrone her. The rebels were quickly approaching London, and the Queen had few trustworthy men to man the defense of the capital. As the war inched its way closer to Mary's home, her advisers were split on their advice to Mary. Gardiner wished for Mary to leave London for the sake of her own safety, while Renard and Paget insisted she stand her ground. As if the events unfolding weren't gloomy enough, the lords in charge of the defense of the capital, the earl of Pembroke and Lord Edward Clinton, were originally in favor of Northumberland's attack of Mary when Edward VI had died. Although the two men were forgiven by Queen Mary, and even saw the potential attack on London as nothing but a hyperbole, their "loyalty to her...was unproven." [48]

Amid all of this chaos, the only person who showed consistent calm and courage was Queen Mary herself. In the face of a great ensuing battle, the people of London were worried that her administration was not handling the rebellion effectively. In fact, the people called the government's response to break up the plot, which the government knew was unfolding, "inadequate." But it is in the face of adversity that a leader is born—and Mary was a true leader. She gave a speech to the aldermen (the City of London council members) and to the people of London attempting to instill faith and hope that the English crown would come out on top. She expressed her love for her people when she says:

"On the word of a prince, I cannot tell how naturally the mother loveth the child, for I was never mother of any. But certainly if a prince and a governor may as naturally and earnestly love her subjects as the mother doth love the child, then assure yourselves that I, being your lady and mistress, do as earnestly and tenderly love and favor you." [50]

Here we see Queen Mary expressing her motherly love for her country. She was resolved to guard it as much as a mother protects her child. She also noted that her marriage would always "come second to her commitment to England." She further went on to assure that she would disassociate herself from the marriage to Prince Philip if the "nobility and commons in the high court of parliament" rule that the marriage was not beneficial to the kingdom. [51] Yet the House of Commons had already pleaded with Mary not to go through with the marriage to Prince Philip a month after she was offered the Prince's hand in marriage in October 1553. Although she truly was not prepared to alter her decision to marry Philip, her speech got the reaction she was hoping for—loyalty. When Wyatt arrived at London Bridge on February 3, 1554, two days after she made the speech, the City of London was well guarded by loyal forces. When arrows struck her window and a direct assault on London was anticipated, she did not flee—even though the advisors all around her pleaded with her to flee by boat. [52]

When Wyatt could not pierce pass Ludgate Hill in the City of London, he faced the music that he would not prevail. He surrendered in anticipation that the Queen would show him mercy much as she had done in the past against those who tried to prevent her ascent to the throne. But the Wyatt Rebellion unleashed the dark side of Mary. No more would she be walked upon by her transgressors. At this moment, the merciful Mary had been diminished—and a mighty Queen had awoken.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top