Writing The Perfect Scene

This chapter is thanks to Dr. Randy Ingermanson and Dwight Swain's "Techniques of the Selling Author". Ingermanson takes Swain's concepts and explains them in a free post on his blog. He also has a lot of books, none of which I've read. This is a distillation of the blog post with some screen shots.

The ideas of Scenes, Sequels, and Motivation-Reaction units are from Mr. Swain. These are incredibly poorly named because they're using terms often used to define other parts of writing. I'm going to rename them in this chapter for (hopefully) greater clarification.

The Beat (Motivation-Reaction United)

This is the smallest element of story. I've had questions about defining a beat, and I personally think this is a much better way than Blake Snyder lays out.

A Beat is in essence what Swain termed motivation + reaction. From Ingermanson's website:

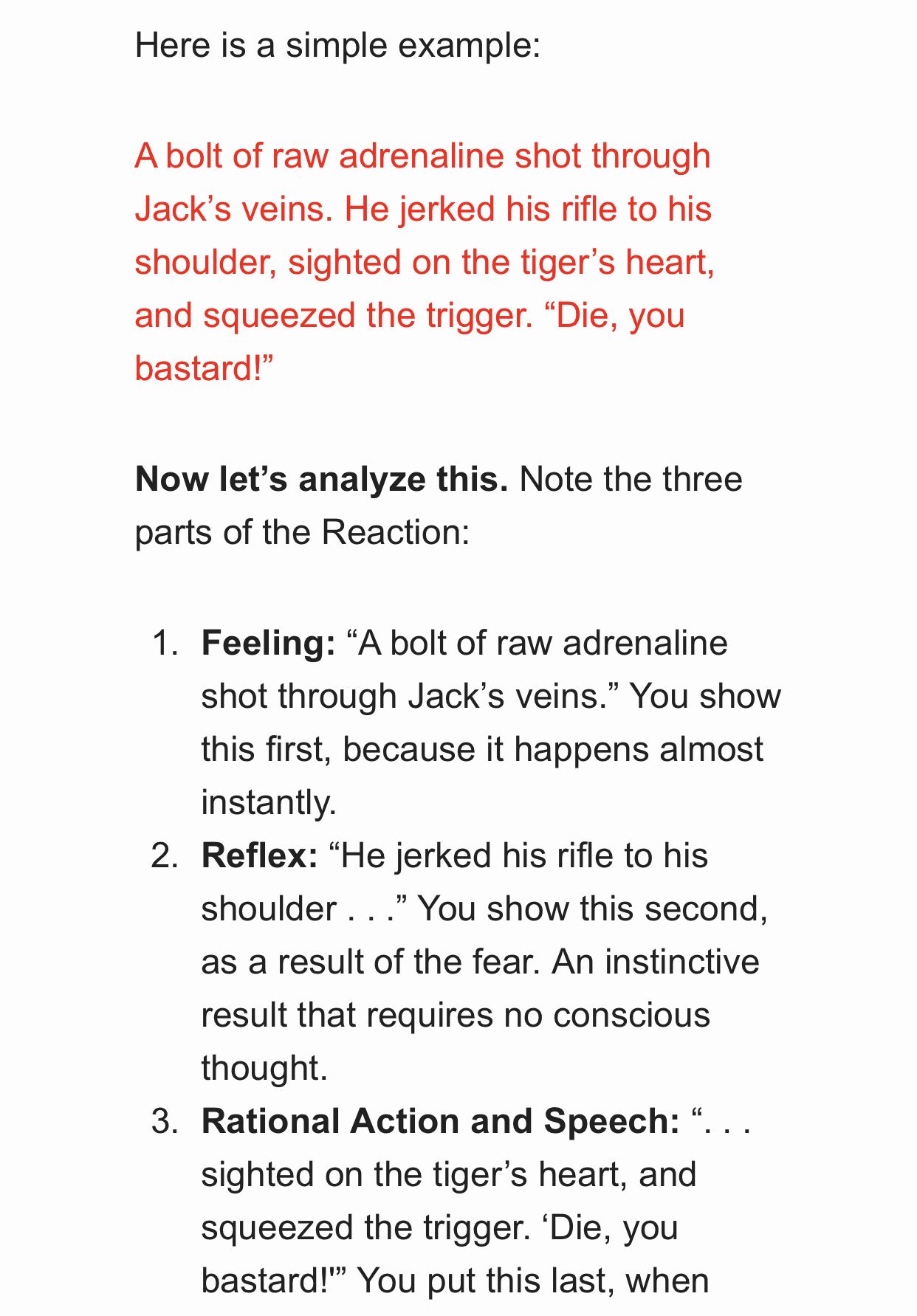

The reaction includes multiple elements of Feeling, Reflex, Rational action and speech.

In essence something happens to your character and your character reacts. This could be done between two characters using dialogue - two people arguing, or with an external force like nature - the tornado touched down.

Your reaction doesn't need to have all three elements of reaction shown above, but it must have at least one, and if you have two or three then they need to be in the above order to make rational sense.

Ingermanson says each element - motivation or reaction - should be in a separate paragraph. This provides clarity for the reader and also allows the author to define the elements clearly and remove anything which doesn't adhere to these beat elements. If it's not a part of a beat then it's not moving the story forward and it's fluff - even if it's the best line you've ever written, kill that darling.

"Scene and sequel"

Here is what Swain says via Ingermanson:

If you look at these, you'll realize they are very similar to the 6 elements of story as previously shown. I do like the terminology for these though. It may be easier for many people to understand. Here is what he says in more detail:

In essence, each of your scenes needs to have the 6 pieces shown above (broken into two sets of three) according to Swain and Ingermanson. This makes sense because in essence the first two elements - Goal + Conflict - create the inciting incident of your scene and move it into progressive complications which are Conflict + Disaster + Reaction. Then the Dilemma is your Crisis, and Decision is the Climax + Resolution. The turn happens anywhere between Disaster and Decision and can even be the very last element which throws you into the next scene.

What I like about the way Ingermanson explains these concepts is that it clearly shows the mirroring of the elements when broken into threes. It feels like a waltz - 123, 123, 123, 123 - and so on. And it provides a good way to analyze your story after you've written it.

Your scenes can be broken up to be either the first part ("Scene") or the second part ("Sequel") or can contain both for a longer scene or a whole chapter. But they have to be one or the other in the end. If they're not then Ingermanson says either rewrite or remove that portion.

The beauty of both the idea of the "motivation-reaction" beat and the "scene-sequel" is they are cyclical. The first part leads to the second and the second leads to the next first part and around you go again.

This cycling effect leads to excellent pacing, which is what keeps readers engaged and not wanting to put your book down. I'm going to get into pacing in a separate chapter, but this is a great tip for analyzing your manuscript's pacing.

I hope you found this helpful! If you want to read the blog post that inspired this chapter you can read it here:

https://www.advancedfictionwriting.com/articles/writing-the-perfect-scene/

Please consider voting for this chapter, and let me know if you have any questions about the material.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top