Chapter Ten

The plague struck livestock first.

Every morning, shepherds and cowhands came to Achilles with the news that more of their sheep and cows had died. Herds and flocks that were hail and hearty at nightfall were decimated by daybreak. Swarms of flies covered sleek hides and soft wool, now clotted with dried blood and vomit.

Achilles ordered that the diseased carcasses be burned to stop the plague from spreading. Wherever Briseis went in the camp, she could smell roasting meat. You would think they were preparing for a feast.

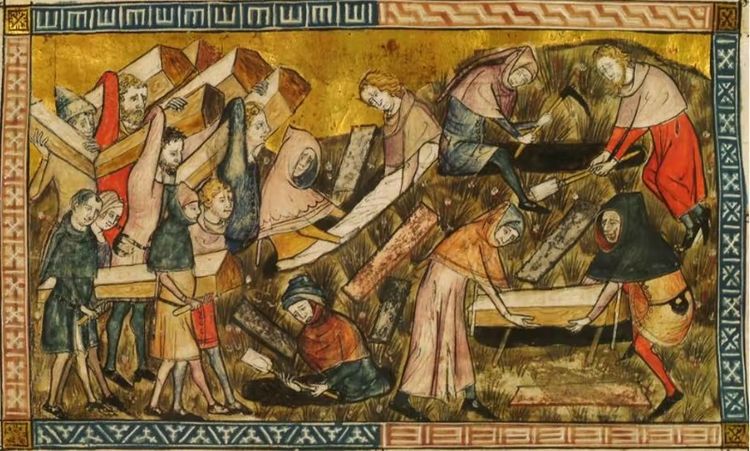

The shepherds and cowhands were the first humans to succumb to the plague.

It started with shivers and, at first, seemed to be a simple fever. Those afflicted were wrapped up in wool blankets, despite the spring warmth, so that they would break a sweat. When Briseis made her daily half-mile walk to the infirmary set up inside an abandoned temple, she would help by tucking in the patients' blankets. She held cups of water to their lips, placed cold compresses on their foreheads, and hoped the fever would run its course before reaching its final stage: where they coughed up blood until they died.

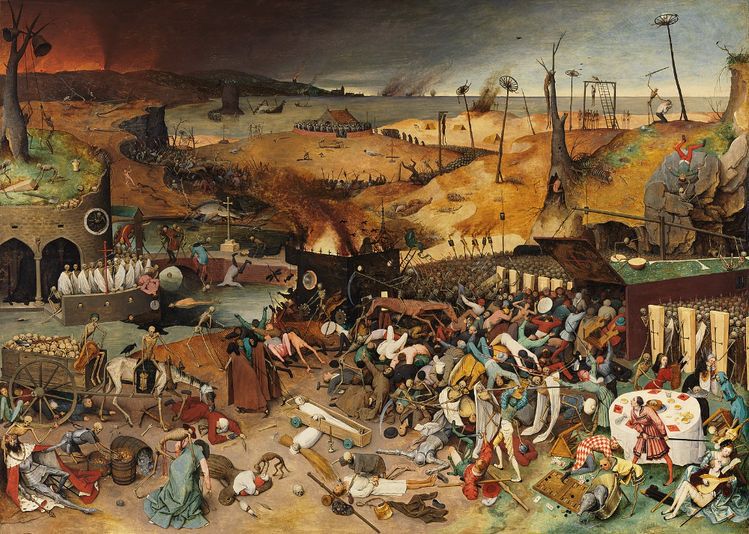

Day or night, you couldn't escape the glare of funeral pyres. Nor the stench. Briseis carried bunches of dried lavender with her wherever she went to keep from gagging. Now, the roasting meat she smelt was human rather than animal.

"It'll pass soon enough," Agamemnon said to the crowd gathered in front of his tent, demanding to know what should be done about the plague. Yet another pyre had been lit. Its noxious black smoke blanketed the camp. Briseis, who watched the interaction from the entrance to Achilles' tent, brushed a greasy cinder off her shoulder. "Begone, all of you. Such a large gathering will only make it worse." Agamemnon disappeared back inside.

"He drinks crushed emeralds dissolved in water," Patroclus said that evening at supper. They had porridge made from mashed apples, milk, breadcrumbs, and honey which was believed to treat the humor imbalance that made you vulnerable to the plague.

Briseis didn't know if this remedy worked, but it made a nice dessert.

"Hmm," she replied to Patroclus. But, unfortunately, she had been preoccupied with feeding the orphaned ewe-lamb Cressida had given her as a pet. Hagne, as she was called, sucked from a milk-soaked cloth that Briseis had tied to her finger.

"They take it as a preventative. It's supposed to keep you from falling ill."

Achilles grumbled. "What foolishness."

Briseis nodded. Drinking crushed emeralds was more than a little excessive, even for the richest kings in all Greece.

"Precisely," Patroclus said. "Everyone knows that candied horseradish is the best thing for that purpose."

Patroclus had been perusing every medical text in Ulysses' library to find possible cures, which he then tested out on any subject he could find, usually Achilles and Briseis.

Strangely enough, considering the circumstances, this was the happiest Briseis had ever seen him.

Candied horseradish just happened to be Patroclus' latest fixation and one of the more pleasant remedies he'd subjected them to. Briseis would choose candied horseradish, which she enjoyed as a snack, over vinegar-soaked onion and dung poultices.

During the day, Briseis did what little was in her power to help the sick and dying. She knew little about medicine and didn't have the strength and stamina to carry buckets of fresh water from the stream to the hospital, but she could mop fevered brows and hold trembling hands.

This plague was a just punishment visited upon the Greeks for their sins against the Trojans. But, life hadn't yet hardened Briseis enough to be able to watch someone, even an enemy, suffer an agonizing death and not pity them.

Briseis either helped out at the hospital or went to gather fragrant herbs. When burned, their smoke purified the air of the miasma, which caused the plague. While exploring the woods and fields near the Greek camp, she came across a bay-laurel tree, a plant sacred to Apollo. A few of its boughs would end up in Briseis' basket along with sage leaves and stalks of wormwood and meadowsweet whenever she went foraging.

At night, when Achilles and Patroclus believed she was asleep, Briseis snuck away to a grove of pomegranate trees along the path to the beach. She carried an incense burner filled with crackling bay leaves. Her prayers wafted to heaven on clouds of aromatic smoke as she made her way through the camp to the pomegranate grove.

"O Shining Lord Apollo," she whispered. The entire camp was quiet and dark. The only light was the faint glow of dying funeral pyres off in the distance. "Please send me a sign. What do we need to do to earn your forgiveness?"

The answer was obvious. Apollo sent this plague as a punishment for Agamemnon insulting Chryses, and the only way amends could be made was if Cressida were allowed to go free. But, it would take a god-sent omen to convince Agamemnon to do the right thing.

Briseis' prayer was answered a few days later.

Cressida showed Briseis how to find patches of wild rue and garlic in the meadows where she sometimes grazed her sheep.

"Wild garlic makes a delicious seasoning in soups and stews." Cressida picked a bunch of delicate white blossoms from among the hundreds growing between two maples. "And wild rue can be used to flavor meats and cheeses but can be dangerous if you use too much." She plucked a sprig from a small shrub covered in star-shaped yellow flowers. "I'd avoid it altogether if you wish to give Thessaly an heir."

Briseis lowered her eyes toward Cressida's flat stomach. Perhaps she used rue to keep from falling pregnant by Agamemnon? In all the months that had passed since Agamemnon first forced his way into Cressida's bed, she hadn't so much as missed a monthly course.

A crow landed on a branch of one of the maple trees. It cocked its head and cawed a greeting to them.

"Good day, Master Corvinus," Cressida said. She reached into a pouch hanging from her belt and sprinkled seeds and breadcrumbs on the ground. The crow flew down and pecked about in the grass.

Two of Master Corvinus' friends joined him to partake in the feast. Cressida had to scatter another handful of crumbs and seeds. "Crows are Apollo's sacred animal. They keep tamed ones at my father's temple. We used to feed them together whenever I visited him." A tear rolled down her cheek.

Cressida flicked the tear away, took a moment to compose herself, then fed the four new crows who'd arrived.

There were now a total of seven.

Briseis made a fist and bit her lip to keep from screaming. There was no justice in this world. They suffered, Cressida not least of all, because of Agamemnon's pettiness. But, Briseis would do well to adopt some of Cressida's self-possession. Only a foolish woman threw tantrums about things that were out of her control.

"Who knew there were so many crows in all of Troy," Briseis said to Achilles later that afternoon. They were standing by the horse paddock, watching Patroclus exercise Cheveux-de-Paille, a pretty, chestnut-colored mare with a flaxen main and tail. "There must have been at least a dozen of them and they fed from Cressida's hand like tame pets."

"There are so many crows because there's so much carrion," Patroclus said. Cheveux-de-Paille had finished going through her exercises and Patroclus was rewarding her with a delicious-looking purple carrot.

Achilles laughed. "Where's your piety, Patroclus?" he said.

"Piety and superstition are two different things."

Briseis made a faint hrmph. Augury might not be practiced in Greece, but it was a venerable Trojan tradition.

"One man's piety is another man's superstition," she said. "And one man's superstition is another man's piety."

"She has a point," Achilles added.

Patroclus covered his face with his hand. "Don't tell me you're going along with such nonsense."

"And even a king has to obey the Gods." An awkward, impish grin distorted Achilles' face.

Briseis giggled. "Especially a king." She and Achilles had the same idea.

"Whatever you're plotting," Patroclus grumbled. He grabbed Cheveux-de-Paille's reins and led her toward the entrance to the paddock. "It won't work with Agamemnon. If he didn't believe Apollo's high priest, he certainly wouldn't believe you two."

Achilles shrugged. "We wouldn't be telling Agamemnon anything he doesn't already know, whether he wants to admit it or not. If the truth offends him, then that's his problem."

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top