#LiveLaughLove

"Microwaves," I said to Paulo.

"Microwaves?" he replied, looking at me like he'd just realised he'd let a lunatic out of the asylum.

I nodded. "Electromagnetic radiation. Microwaves. You know? From mobile phones."

Paulo frowned.

"Look, So you said you guys don't have full connectivity, right?"

He nodded. "Just satellite, a few hours a day."

"Which means the phone mast at the hotel—you must have seen it, when you came down, when I had hypothermia—is the first electromagnetic transmitter this far south, right?"

Paulo looked uncomfortable, and said, "Um, I suppose."

"Mobile phones work via electromagnetic radiation. You're a scientist, you must know this."

He side-eyed me defensively. "I'm a marine ecologist," he said. "It's not my field. Phil would probably know." He looked uncertain, obviously weird about bringing her up.

"Well it's true," I said. "3G, 4G, whatever, it's basically short-wave electromagnetic radiation. Microwaves. Which means when that mast went up at the hotel a few weeks ago, it will have changed the electromagnetic charge of the area. Maybe by enough to interfere with the whales' internal navigation systems, accounting for the change. The timing is right, isn't it?"

"A few weeks ago. Yeah." Paulo frowned at his screen and nodded. "Did you think of this just now?"

I nodded and he raised his eyebrows.

"Wow," he said. "That's pretty smart."

"Well, kind of," I said. "I read an article in the Ecologist last year about how phone mast radiation messes with the navigation of birds. That's what made me think of it. So whales could be the same, right?"

He nodded, chewing on his bottom lip. "Yeah," he said uncertainly, taking it all in.

"Look, I know it sounds kinda vaccines cause autism, but it's totally scientifically plausible."

What I didn't say was that I also suspected the radiation from the mast was somehow affecting people neurologically, driving them to snowy suicide.

That was less scientifically plausible—phone masts are everywhere in the modern world, after all, and we all carry on with our lives—but maybe if this was be a particularly strong signal because of the isolation, or if it interacted in some way with the electromagnetic charge of the Pole...

Whatever the mechanism, it made much more sense the mystery deaths weren't the nefarious plan of some powerful government, but an accidental result of the foolishness and hubris of humanity.

Just as we'd poisoned our planet with pesticides, destroyed the oceans with plastics and burned up the atmosphere with CFCs, perhaps we were now finding that the miracle of constant connectivity wasn't as benign as it initially appeared.

No war was more brutal than the one we waged on ourselves.

"We could ask Phil," Paulo said awkwardly. "This is more her area than mine. Though maybe it's better if I do it alone."

"Her machine—the radiometer," I realised, "thats electro-magnetic, right? Didn't you say that had been acting up too? It all adds up! It's got to be the mast!"

I slammed my fist down on the table in victory at it finally slotting all together, then withdrew it quickly, embarrassed.

"If it is," I went on, blushing now, "we've got to do something about it. Get the hotel closed down, or at least the mast removed. If it's affecting the animals, or interfering with the science... it needs to be stopped."

I looked at Paulo. His big dark eyes were set on me, and he was nodding.

"I work—worked—at GlobalGreen," I said. "I know how they run their campaigns. If it is the mast—and I'm sure it is—I could help you. We can get it removed."

Paulo looked away for a second, up towards the ceiling, his shoulders tensing.

Then he turned back, dark curls tumbling softly on his forehead, those long dark lashes glinting in the light.

Was he going to cry?

"Sorry, Jennie," he wiped his eyes with the back of his hand, his composure quickly restored.

"I've been losing my mind out here for months. I couldn't... With my work, all the isolation, my troubles with Phil..."

"It's okay," I said. "I just broke up with someone, too. Eight years. I know what you mean."

He shook his head, dark hair dancing over his brows. "I've been so...wound up, for so long. I'm sorry if I haven't treated you how I should these last days. I think I forgot how to be around people."

"It's okay," I said. "I understand. I do."

I leaned in to give him a hug.

Every nerve in my body—including the more intimate ones—crackled at the contact, like I'd been shot with an electromagnetic force.

I pulled away, hoping he hadn't noticed my intense reaction.

He rested his hand on my shoulder and squeezed it, a calloused thumb whispering gently against my neck.

"Wee Jennie Jamieson," he said, the touch of Scottish leaking back into his voice. "The girl who has all the answers."

The movement of his thumb on my neck was making starbursts erupt all over my skin, each one fizzling then melting, trickling down my synapses to a molten pool between my legs.

Paulo looked at me, and I didn't know what he was thinking.

This was nothing like Ruben.

This time, I kissed him.

***

Now, like I said before, I don't think I'm in much of a position for doling out life advice, but I would say that if you're thinking of French-kissing a man who's done a long stint trapped on an Antarctic research station, you probably want to make sure you're definitely into it.

Because things are likely to escalate pretty quickly.

I was definitely into it.

As we lay in a tangled, semi-naked—and warm! God, so heavenly to be warm!—heap on the carpet on his office floor, Paulo's arm around my shoulders, fingers twirling through my hair, I blinked, dazed and blissed-out, little snowflakes of pleasure dancing in the corners of my vision.

"You were always my favourite," Paulo softly said.

"You too," I replied, watching his diaphragm rise and fall slowly as he breathed. "Is it true you were born between South Shetland and Orkney?"

"Yes," he said. "You too? But the original ones?"

I nodded, the skin of my cheek sliding tantalisingly against the warmth of his chest.

"That's nice," he said. "Symmetrical. But it was not so nice an event. My mother died. Complications in birth."

I stroked the warm flesh of his arm, and he squeezed my hand.

"I'm sorry," I said.

"It was not your fault. It was my father's fault. The Argentine government's fault. They were doing the thing, like Davey said, shipping out pregnant women so the children could be born in the Antarctic. Then my mother's labour... they tried to sail her back, but they were too late. She didn't make it."

"That's awful," I said. "So did your father bring you up?"

"Kind of. Not really." Paulo inhaled deeply. "He was the head of Belgrano, the biggest Antarctic research station." His inflection on the word Belgrano was different, reminding me he could speak a whole other language; access a whole world that was alien to me.

"I went to school on the ice as a small boy. It's the only school on the continent. Part of that imperial bollocks,"—that trace of Scottish, again, on the swear word—"staking their territorial claim. Then at twelve I went to boarding school in Buenos Aires. University there too. Then to the U.K."

"Do you get on with your father?" I asked.

He shrugged, his shoulders moving beneath me. "I went between rebellion and trying to please him as a child," he said. "I disowned him at one point, blaming him for my mother. Declared I would stay only with my abuelos, my mother's parents, when I was home from school. They lived on a farm, just north of Buenos Aires, in the country."

"That sounds nice," I said.

"It was and it wasn't. They were Tehuelche, it's an indigenous tribe. But with school, my father, growing up out here... I couldn't even speak the language. I didn't know their ways, didn't understand farming. They were strangers to me."

He sat up and rolled above me, pinning me to the floor, kissing my hairline.

"But why do we speak this sad story of the boy with no home? I want to learn about you, your whale island."

"Isn't Antarctica your home?" I said.

He lay back down, his arm under my head, stroking my hair gently with his hand.

"This is no-one's home," he said. "You're an ecologist, you know that. Our species doesn't belong here. We have no niche."

"Yes," I said. "That's been gnawing at me ever since I arrived. I can't shake the feeling that I don't belong here. We don't belong here. People. So why do we come?"

"That's why," Paulo said. "We come because we're not invited. We come because we shouldn't. Just to show we can."

"Like Everest," we both said in unison, and then we laughed.

"Yes, I hate Everest," Paulo said. "If you tell me you climbed Everest I never respect you again."

"I know, right?" I said. "All the chains of people constantly going up, the bodies, the rubbish everywhere..."

"And they climb past the dying man. Just to get to the top. Just to say they can."

"Everest blows," I said.

"Agreed." Paulo smiled, shaking his head languidly, his hand brushing the soft flesh of my bottom. "I never want to move from here."

"Let's not," I said.

Warm, comfortable, happy, we drifted off to sleep.

***

I was woken by a rattling, buzzing noise, surprised at how deeply and peacefully I'd slept, how contented and happy I was.

It was a phone going off, I realised, vibrating on the desk above us, casting a square green pall of light over the beams and tiles of the ceiling.

I sat up gently, trying not to wake Paulo. It was dark, thickly quiet, and I had no idea what time it was.

I reached for my phone before realising I'd left it in my coat pocket.

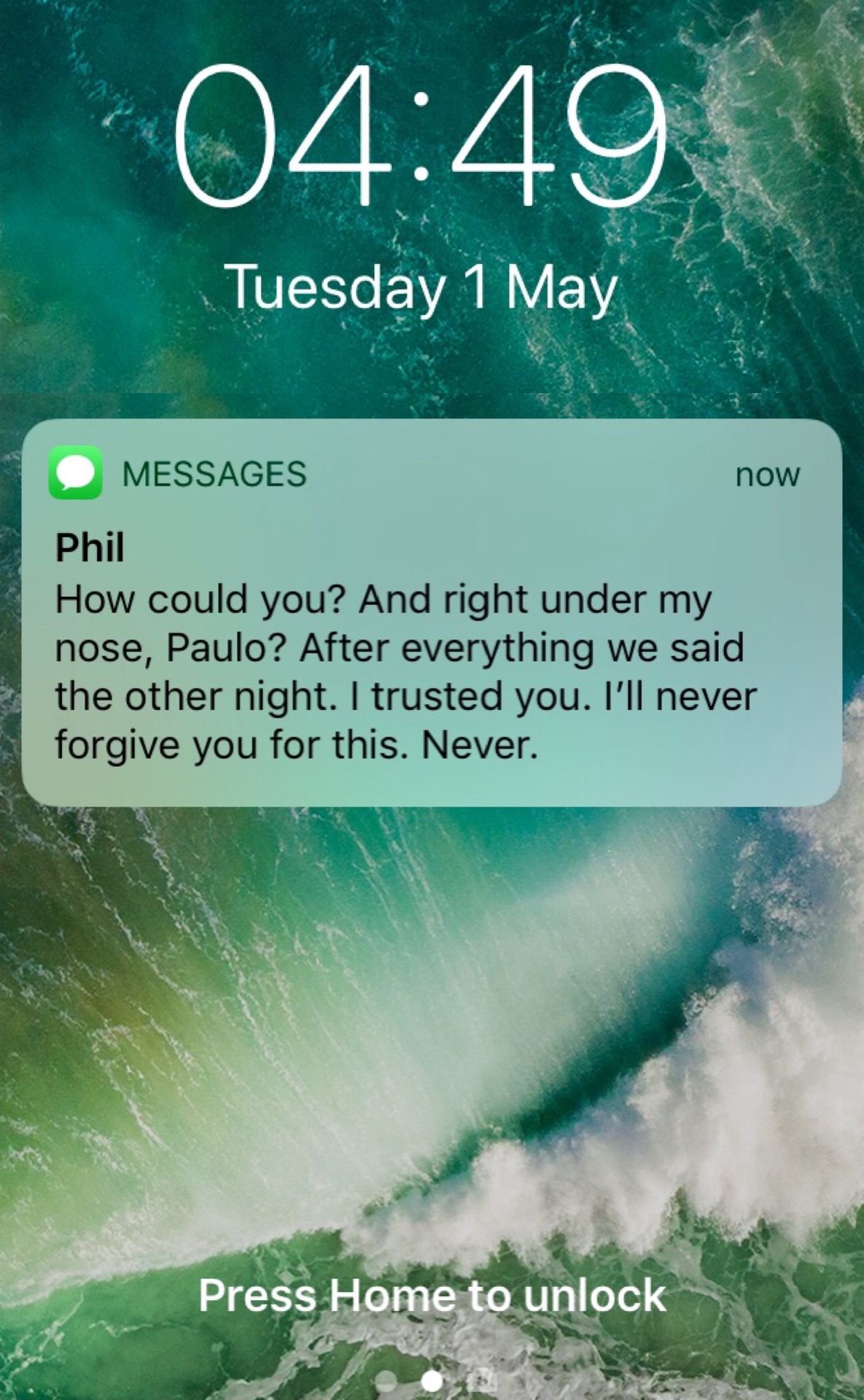

It was Paulo's phone, on the table. The connectivity must have just kicked in, bringing messages and emails with it.

Easing myself up, I peered at the desk, to see if I could get a glimpse of the time.

I was right, we were connected. Paulo had got a message.

It's not like I was snooping.

It was there on his lock screen, for anyone to see.

I sat back down, my legs going wobbly beneath me.

It looked like Paulo and Philomena weren't so over after all.

Anger, disappointment and shame wrapped around me, a possessive embrace squeezing me tight.

What an utter cunt.

How could he do this to me?

How could he do it to her?

This was Ruben and Suzie, Ben and Jocasta, all over again, but a thousand-zillion times worse.

There was no way I could stay there.

I looked over at Paulo, sleeping, as peaceful and perfect as an Elgin marble, and my heart withered and died in my chest. I couldn't bear this. I had to get away from him. As far away as possible.

And if that meant setting off alone into the polar night, then so be it.

I gathered my clothes, as quickly and silently as I could, my eyes stinging.

Paulo barely moved, his breath deep and even and slow.

I'd ridden a quad bike, helping round up the sheep on the heather moors, back in Shetland.

I was sure I could work out a snowmobile.

Holding my breath, I struggled into my clothes, and tiptoed out into the night.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top