35. Toward Shelter

Elizabeth heeled about fifteen degrees to port as she sailed north-east half north with the stiff wind a point forward of her starboard beam. By her taffrail log, she was making a steady eighth less than twelve knots, and as three bells of the first dog sounded, she had been at this course and speed for nearly three and a half hours.

Aldrick checked the transit board, the deck log and the DR, then he turned to Franklin and said, "By calculation, we should see the highest point of the ridge a bit beyond twenty-five miles, but in these conditions, we will not likely raise it before twenty. We are about that now."

"Aye, Sir. I have the lookouts warned for ahead to two points on either bow."

"Very good. I shall be below."

"Aye, Sir."

Below, in the great cabin, Elizabeth greeted him with a hug and a kiss. "How far now?"

"Less than twenty miles by DR; the lookouts should raise it within a quarter hour."

"More than that. It will take us much of an hour to be within ten."

"Ah, but we must add the height of the ridge. Our lookout's distance to the horizon is ten, and from the island's ridge top, the horizon is fifteen and a half, so the sum is above twenty-five." He pointed out the stern windows. "But it is too hazy today for it to show at that distance."

Aldrick opened the chart drawer and withdrew a folder of anchorage plans, leafed through it, selected one and placed on the tabletop.

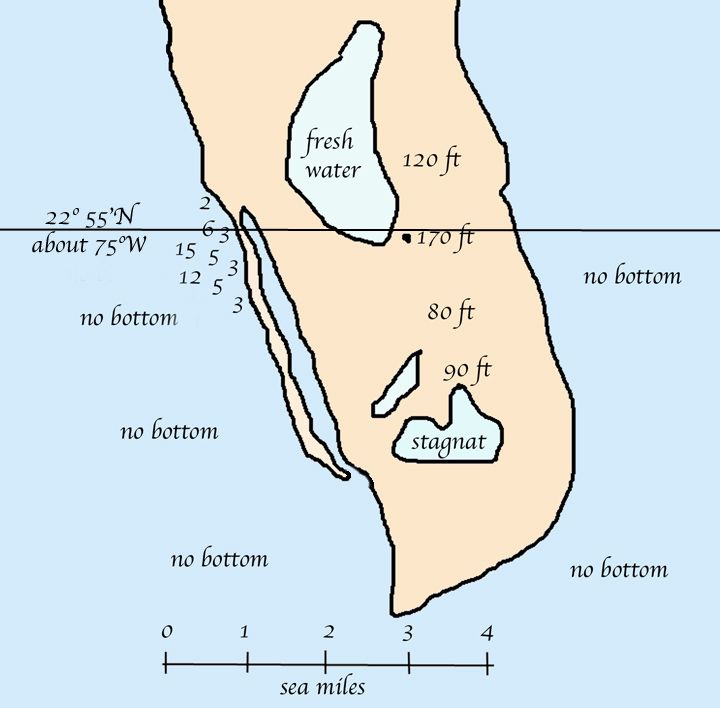

"We are headed here, and this 170 is the height of the highest point of the ridge. You can see the protection this provides from the prevailing easterly winds, as does the land from storm seas."

"This looks like your hand. Did you draw this?"

"I did, and it is among the many I made pantographs of for Moll, Machin, Price and others, so we may all have safer navigation."

"What do these no bottom marks mean?"

"They indicate where the water is too deep for the sounding line to find bottom, so over fifteen fathoms, ninety feet."

"But with a longer line, how deep is the bottom?"

"We do not yet know. What we do have are records of Drake's attempts to measure the depth of the Pacific Ocean using a weighted line half a mile long without finding bottom. And many have tried since him." Aldrick shrugged. "But we are not concerned with any depth beyond fifteen fathoms, so greater than that, we mark as no bottom."

"Why fifteen fathoms?"

"We carry three shackles of cable on each of the anchors, a shackle being a measure of fifteen fathoms, and it is not safe to lay to less than three times the depth. It is not the anchor which holds us, but rather the weight of the heavy iron links of the rode ranged out on the bottom."

Elizabeth nodded. "So, this is the reason we were still moving when you ordered let go. To range it out." She grimaced. "Just before Roberts fired. I do hope we have a more peaceful time here."

"I would expect it to be as quiet as on our previous visits; not a soul else but us. There is fresh water, but its access is remote and tedious, and there are far better choices on other islands. There is little else here but near-endless strands of white sands lapped by warm water."

"Ooh! Will we be able to bathe in it?"

"Yes, certainly. I find the saltwater invigorating on my skin, but care must be taken to not drink it. I can teach you to swim, if you wish, both atop and beneath the water, and we can watch the vividly coloured fish."

"Father taught us to swim in the Avon at the foot of the south gardens, and I have delightful memories of frolicking in the water every summer with my brothers. " Elizabeth giggled. "Until Mother thought it unwise that I continue being naked with them." She giggled again. "I had asked her if Thomas' foretail standing proud meant he wanted to mate."

Aldrick guffawed. "This is so like you. Always curious and inquisitive. Likely how you knew about mating. Just simply asked."

"No, but this began the talks with Mother. I had learned earlier by observing."

Aldrick tilted his head. "By observing?"

"By watching the horses. Their interactions had fascinated me from the time I first saw a stallion grow long."

"How old were you then?"

"Six, maybe seven when I first watched them mate."

"And when your mother decided it was unwise to be naked?"

"That was five or six years ago." She shrugged as she thought. "The year before my first season in London, so I would have recently turned sixteen."

He looked down at the curves of her bosom. "You would have been into your blossoming by then. Little wonder your brothers were aroused."

"Only Thomas though; he was fifteen, and he had begun to grow bigger over the winter. But William, Henry and George were still tiny." She held up her little finger. "Not near as big as this."

Aldrick nodded. "If we go ashore to frolic, we will go to a place separate from the crew. There is no sense inciting their natural response."

"Did you frolic with your brothers and sisters?" Elizabeth pouted. "You have not spoken of them, nor much at all about your family."

He blew out a deep breath. "Both my brothers died of illness in their youth. Frederick I remember, but I was too young to be aware of Matthew. My sister, Martha, is the only child but me to have survived past a few years."

"Oh, no! My inquisitiveness again. Why was I not introduced to Martha?"

"She is feeble-minded, much as a five-year-old in behaviour and ability, and since Mother's death, she has lived with my Aunt Alice."

"Oh!" She winced. "I must stop my incessant questioning. But you must take me to meet her when we return. And your uncles and aunts and cousins and..." Elizabeth paused when the whistle sounded.

Aldrick uncovered the voice horn. "Captain."

"Officer of the Watch, Sir. We have raised land."

"Thank you, Mister Franklin. I shall be directly up."

Elizabeth followed Aldrick up the ladder to the quarterdeck, and she listened as Franklin added details. "In and out of the mists, Sir. Fine on the starboard bow. And we now have dark clouds over the horizon."

"Thank you. What is their movement?"

"They have not been visible sufficiently long to assess, Sir." He pointed up the mast. "I have sent Reynolds aloft to observe and report."

Aldrick examined the transit board, the deck log and the DR plot. "There remain fourteen miles — an hour and a quarter. A bit less than that until twilight." He confirmed with a glance at the sandglass. Then he raised his voice to be heard above the increasing roar of the wind. "Do you remember the anchorage, Mister Franklin? We may have to feel our way into it in fading light."

"And likely in squalls, Sir," Reynolds shouted as he bounded onto the quarterdeck from the shrouds. "A dark band of them growing over the horizon broad to starboard."

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top