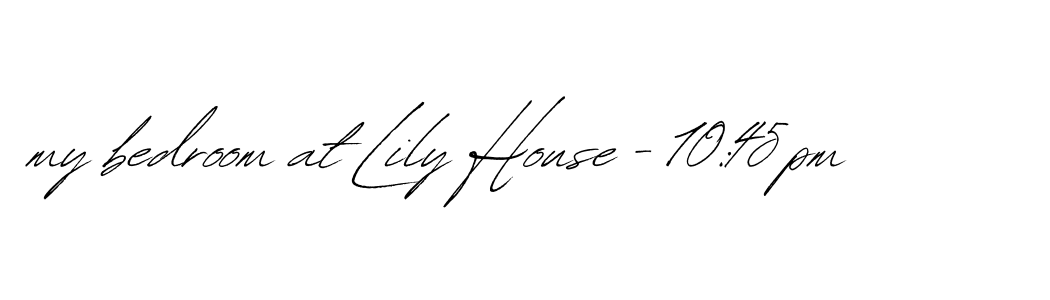

June 29, 1882 - Merritt

Although I have much to write about this evening, what with Hanny's arrival and our trip into town, I believe it is time that I write of myself in a way I have neglected to do up until now. I have had the truth weighing on my heart for too long and I shall forget about today's events in order to recount my past instead. I am secretive by nature, life has taught me to be, but with Dr. O'Donnell's letter to Gabe, I have been shown what the world believes me to be.

I wish I could say I am shocked by what Dr. O'Donnell has written of me, but I am not.

I do not know what this new journey with Dr. Abaddon—Lucius—holds in store for me, but I refuse to not have a say. For my own insurance, I will write of myself in all honesty here. I shall give my defense, or rather, my explanation. It has been weeks since I received this journal and no one has encroached upon my privacy. I believe myself to be safe to allow my guard to drop, even if it is only in these pages—

Her name was Clara Harris and she was twelve years old. I neither know how she found herself in the possession of a sharp piece of glass nor why she was condemned to a place such as St. Agatha's. Despite such claims, I was never meant to be watching her and I was not doing such a task on the fifteenth of November. Instead, I was in the great room where I'd been given clearance to teach a few of the children to read. When I arrived, I found that Clara was missing from the usual group. I did not think anything of it and none of the nurses or nuns present asked after her. I taught a brief lesson, passed out slates and pieces of chalk before instructing the children practice writing their own names. It was then, with my lesson finished and the nurses chaperoning, that I excused myself to go clean the chalk dust from my hands.

I found her in the water closet, dressed in only her white nightgown, sitting in a bath of water and blood. I nearly choked on the smell of copper and citrus soap as I opened the door. She had left it unlatched, perhaps in hopes that someone would find her corpse; I do not believe she wanted to be stopped.

Clara had always been small for her age, malnourished and emotionally tormented. Just then, sitting in that tub with her black hair wet and falling about her face, she looked like a horror. Tears streamed down her cheeks and her skin was drained of almost all life—even if I had called for help it would have done no good. She was dying. I knew it in my bones in a way I'd never known anything before. I had known of pain, but not to the extent of death itself. Never to the extent of wishing for death, not the way that this child wished for it.

Since I was a child, I have experienced the siren song of other people's pain. I cannot feel my own aching, but that inability remains contained in me and I am somehow able to push past it. My mother used to think that because I was numb to my own hurting, I was especially in tune to the agony of others. I believe she is right. Was right. I do feel pain sometimes, but it has never been, and probably never will be, my own.

I both see and feel pain the way that others can both see and feel steam rising from soup. It is black and swirling, a thin mist that envelops a person until they are wrapped entirely in its dark embrace—this is what pain looks like to me. They do not see it, only I do—for I am doubly cursed, never to suffer for myself but to suffer for others.

It is because of this knowledge of myself that I have always been very careful about not touching people who are in the midst of such hurt. There are levels of pain, ones that are made known to me through visual evidence. Small things such as paper cuts or small disappointments come in whites or greys. Things become darker as the emotional or physical pain becomes worse—that day Clara was shrouded in pitch black.

She was in such turmoil, such agony both in body and mind that I could not stop myself from reach out to her. It was a mistake, as was not yelling for help as soon as I saw her—but I was stupid and it had been such a long time since I'd really felt human, felt alive...

I am ashamed of the person I was in that moment. I am ashamed that I was weak and that I wanted to feel something enough to stay where I was. To an outsider, it may have appeared that I was comforting Clara, but I was not. I was drinking in her pain, reveling in a sensation that I am incapable of experiencing on my own. With her hand in mine, I felt the burning of torn flesh, the coolness of the tub and bathwater, the warm slowly creeping its way out of my body. It was achingly painful and slow, and I loved it. I should not feel bad, for in taking Clara's hand I did spare her the agony of her own last moments. I have learned that two people cannot share the same pain, at least not directly. With my touch, the brush of my fingertips to her cool skin, she was made numb. For a few blissful seconds, I was normal and she felt the sensory silence that I live with on a daily basis. She did not feel a thing as she died.

And so I was found, on my knees next to a bathtub full of blood, holding the hand of a dead girl. I was yelled at, restrained and locked inside of a bare white room with no outside contact with anyone. My only possession was a stripped bare mattress. There was one door and no windows. I was only allowed out of that room to go to the washroom and those trips were heavily monitored. Although I was never charged with doing anything, as they had no proof that I had committed any crime against Clara, I was still treated as a criminal. I lived like that ninety-two days—the equivalent of four full months. I saw no one and spoke to no one, my only visitor was Dr. O'Donnell and he barely spoke to me.

He just wanted to know why I'd done it. Everyone wanted to know why I had done what I had. Why didn't I call for help? Why had I allowed a little girl, someone I should have considered a friend, to suffer and die when I might have been able to save her? I never did tell him the real answer. He insisted that if I were honest with him, told him why I'd left her to die, I would be allowed out of solitary confinement. I eventually caved and told him that I can sense the pain of others. I did not explain it to him in detail, as I have never explained it to anyone in as much detail as I just have in these pages. But he was given the information.

What I did not tell him was that I know why Clara Harris suffers the way she does. I did not tell him that her father is an alcoholic and that her mother died when she was born. I did not tell him that it was Mr. Harris who placed the blame on his daughter's thin shoulders. I did not tell him that she sleeps in the bedroom next to mine and that I hear her crying herself to sleep at night. I did not tell him that she does not eat because she has been taught all her life that she is not deserving of food. I did not tell Dr. O'Donnell that Clara wanted to die so that she would not have to ever go home again. Unlike me, unlike so many of the girls at the home, she did not crave being normal.

She craved being dead.

I held her hand and took her pain—and let her die.

I knew it was wrong and I still did it, because I have never known how to stop being who I am. I am a selfish monster and no amount of denying it will make it less true. But I wish that it would. How I wish I could pretend that I was like everyone else, but I have never been able to do that.

The members of my family had always known I was incapable of feeling pain. This inability became clear when I started gnawing on my own fingers. It was for this reason, that we had a nanny. She would stay with me day and night in an effort to keep me from hurting myself. Being a toddler who could not feel pain was quite frightening for my mother. When I wasn't trying to eat my own tongue, I was busting my head on a table corner or trying to stick my hands in the fireplace. The colors didn't begin to appear until I was older.

My earlier memory of them is of five year old me sitting on a bench next to Lora in a train station on our way to visit our grandparents. She was pointing to people and I was whispering to her, describing the colors only I could see. My feet swung from the bench and I leaned precariously to one side, away from our parents, and cupped my little hands to Lora's ear. I enthralled her and I was thrilled at being amusing.

"What are you two doing?" Mother caught us giggling and slid closer to me on the wooden bench. The smell of roses water and mint filling the air as her arm wrapped around me. "I hope you are behaving."

Lora had beamed, always more open and talkative than I was, and said, "Merritt is showing me the shadows."

Mother's face, young and yet so world-weary from five years of worrying about me, fell. "Shadows?" She leaned her head down, bringing her words closer to my ear. "You mean the shadows on the wall?"

Again, it was my twin who spoke. "No, the ones that are eating people. Merritt says they are like storm clouds."

The grip on my shoulder tightened, as did mother's voice. She feigned a laugh and pulled me closer to her—the problem child. I was the little girl who she teased about making her lovely hair gray. "I shall have lived a million lives when I am done raising you, Ruth Merritt Holbrook." She'd said time and again. At that moment, though, she did not smile or tease, instead she kept her voice very low. "There aren't shadows eating people, we are inside a railway station. The only shadows here are faint, nothing to fear."

"But Merritt says they aren't scary." Lora explained. "I needn't be afraid of them."

Mother had gently placed a gloved finger under my chin and forced my eyes up to hers. "Merritt, is that true?"

I hadn't smiled as I said, "The shadows do not touch me. They can't touch me, not like they touch others."

Suddenly, my mother had looked very old. Her eyes closed for an instant and the breath seemed to rattle in her lungs as she inhaled and then released the breath slowly. When she opened her eyes, she was my youthful, smiling mother again. I received a kiss on the temple followed by a quiet reproach. "You must not tell such lies, my love. Do not speak of such things again. Never again, do you hear?"

I had not been lying then and I most certainly was not lying when I told Dr. O'Donnell about feeling the sadness in Clara. I'd seen the pain in her, felt it myself and I'd taken it away. For me to be able to not only see, but also feel, her pain from a distance then it must have been quite substantial—indeed it was. But the truth rarely matters in those types of situations.

I was already seen as being wrong, my soul darkened and devil-touched. Why should they be surprised when I began saying I could feel the agony of others? Why should they not lock me up and call me insane? I suppose they had every right, to them I was wrong. I had no reasoning and no defense in their eyes. I do not in any way believe myself to be blameless or perfect—but I would like to think myself not a monster.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top