Cricket

No, not the insect. Not the phone company, not Jiminy and not Buddy Holly's backing group either. We're talking about the sport, people.

The magnificent, multi-faceted, bewildering, often infuriating, enchanting and epic contest known as cricket.

Oh, yes. Flannelled fools flailing about in the midday sun. Googlies, long hops and cover drives. Leather on willow. Bat and ball. In fact, according to Wikipedia, the most popular bat and ball game in the world.

And why wouldn't it be? How can you not love a sport where a single game can take not just one hour or two hours or even ten hours but a whole freaking five days? What madman/woman/person (look, it was almost certainly a man, given few women would countenance such a monumental waste of time) ever thought that was a good idea? The scale of the thing is absurd. Glorious and beguiling, but absurd.

And that's just one Test Match. In some series they play five of the suckers. And, in one of those little twists that drive non-cricket aficionados to despair, sometimes, at the end of the five days...

No one wins.

Yep. Cricket has the draw. No, not the tie (although it has those too—twice in the last 150 years). The draw. The games where (wait for it) there is not enough time for a result. Thirty hours of playing time, at least 2,700 balls bowled and neither side gets the gong. Which, weirdly, can be a good thing. Some of the most celebrated games in cricket history are draws. A couple of tailenders, who barely know which end of the bat to hold, seeing off the best the opposition can bowl at them, surviving those crucial final few overs of the fifth day as the sunlight fades and the shadows lengthen and their rapturous fans cheer them along in their relentless, glorious pursuit of not losing.

Test Match cricket is warfare. Sporting warfare, but warfare nevertheless. Tactics and strategy, individual heroics and team efforts, ebbs and flows, walkovers and fightbacks and near-misses. That's the magic of the broad canvas upon which it's played. There is time for a narrative to develop, a story of breadth and detail, with sub-plots and bit-parts and twists and turns, with villains and saviours and triumph and despair and quite often all of the above.

And, just like in warfare, the elements play their role. Cloudy skies and green pitches have seam bowlers smiling, while dry weather and dustbowls suit the spinners. Batters like a nice sunny day and so do the spectators but everyone, and I mean everyone, hates the rain. Boo, rain, boo.

Unless, of course, you're getting your arses spanked and hoping for a draw. Then it's rain-dances and sky-scouring all the way. Send 'er down, Hughie!

Upon further reflection, I guess rain is one of the ways in which cricket and warfare do differ. After all, nobody would have minded too much if they'd called off World War One for bad weather.

Despite the breathtaking magnitude of professional cricket at Test Match level, the game also lends itself to the smaller scale. To the less-than-professional among us. Everyday, in backyards and back-alleys, on roads and on fields, in carparks and on driveways around the world, in India, the Caribbean, Pakistan, South Africa and a multitude of other exotic locales, the cricket faithful bat and bowl and field and appeal and become legends in their own minds.

I couldn't tell you how many childhood hours I spent in my own backyard, a chubby little blonde-haired kid slowly par-boiling under the unforgiving Australian sun as I did my absolute damnedest to grind my friends and siblings and cousins and other assorted loved ones into the bright green kikuyu grass. And them me.

Every Christmas day, come about 3pm, a goodly chunk of the Australian population can be found in their own backyards, beer in one hand and bat in the other as they do their inebriated best to emulate their cricketing idols—with, of course, a few key modifications to the traditional rules.

One-hand-one-bounce catching, so you don't have to put down your drink:-

Six and out (and fetch the ball yourself):-

The shed/house/most drunken person's car playing the role of wicketkeeper:-

And, given the rarity of having a full team on hand, the drafting in of whatever random person/object/crap you can lay your hands on as fielders:-

On the subject of which, I particularly enjoyed this little nugget from the 'Rules for Fielders' section of Wikipedia's article on backyard cricket:-

Dogs are considered fielders, and they effectively switch teams with each innings to constantly remain on the fielding team. If a dog catches the ball (the one-bounce rule is also often allowed), or if the dog (or any other pet) is hit by the ball on-the-full, the batter is declared out. It is the responsibility of the fielding team to chase dogs when required, but ultimately it is the responsibility of the bowler to clean the ball of any slobber.

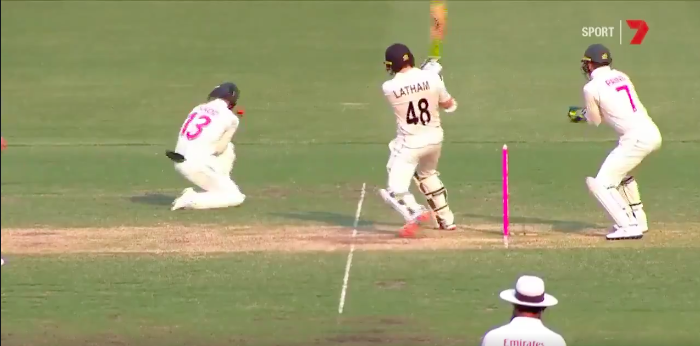

There's no denying that cricket is a game of some...complexity. It can be a little daunting for the cricket neophiles. Bowlers have bouncers, yorkers, wrong'uns and dooras in their arsenals. Batters play hook shots, cover drives, sweeps and square cuts. Fielders stand in the slips, at square leg, down at deep third-man or (if they've really annoyed the captain) at silly mid-on, which should probably be known as suicidal mid-on:-

I've been watching the game for years and I still get my covers and my point mixed up. But all that stuff pales in comparison to the labyrinthine minefield otherwise known as the rules of cricket. Or, as they are officially known, the 42 Laws.

42. I know. A coincidence? I think not.

Let's consider an example:-

Law 36: (LBW). If the ball hits the batter without first hitting the bat, but would have hit the wicket if the batter was not there, and the ball does not pitch on the leg side of the wicket, the batter will be out. However, if the ball strikes the batter outside the line of the off-stump, and the batter was attempting to play a stroke, he is not out.

The umpire's decision will depend on a number of criteria, including where the ball pitched, whether the ball hit in line with the wickets, the ball's expected future trajectory after hitting the batsman, and whether the batter was attempting to hit the ball.

All clear?

In recent years, shorter versions of the game—one-day cricket, T20s, The Hundred, etc—have come along for the time or concentration-challenged, providing options more suited for a night out or in front of the TV or even down the pub. And they're fine, a bit of harmless hit-and-giggle, inconsequential stuff in which the stakes are low and the dollars high. I'll watch them happily and without complaint.

But for me, the gladiatorial epicness (epicnicity? epiciliciousness?) of Test Match cricket is what it's all about. I could go on all day about the reasons why—I know, because I have—but for the sake of brevity and your sanity, I won't. For now, I'll simply restrict myself to a heartfelt:-

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top