6. Of Creative Thinking

Maria lay on top of David, running her fingers across his lips and stroking his beard, quietly talking as she slowly churned her hips. "I loved the expression on Ursula's face when Tante said a quarter million. I wish you could have been there for it."

"I had to choke a laugh at the meek voice that Laurenz used when he asked if she'd still take two thirty-two."

The clock began cuckooing, and David kept count with alternating throbs and gentle thrusts. "Twelve? Was that twelve?" he asked.

"That's what I counted."

"We should get some sleep. One final pop, but again we'll need to remember to be quiet. We don't want to wake anyone."

They were quiet in the morning also, and they surprised Bethia and Rachel when they walked into the kitchen shortly before nine.

Bethia looked up from her coffee and said, "We didn't hear you this morning; we thought you were still sleeping."

"We've been muffling ourselves, not to disturb you," Maria said.

"Oh, don't be so silly. Don't hold it in," Bethia said. "Let out your whoops and your moans. It's so much more enjoyable to give voice to your passions. We certainly enjoy hearing you and being taken back to wonderful memories, to wonderful feelings."

David kissed Bethia and Rachel good morning and then asked what he could do for breakfast.

"The best thing you can do," Bethia said, "is to sit here at the table. Maria and I will get everything ready."

A quarter-hour later, as they began enjoying the breakfast spread, Bethia asked, "So, Sweetheart. I guess it's Sweetheart number three. What does our mastermind see for today?"

"You flatter me, Tante. My mind is completely empty."

"That's an excellent sign," Maria said. "You've told me often that's where creativity begins. It starts with an empty mind. With a blank canvas."

"This is the Klettgauschinken, isn't it?" he asked, picking up a slice, examining it and then taking a bite.

"Yes, my pride, my consistent medal winner."

"You still own the old truck – guess I should call it a lorry, with your British heritage. You'll continue to own it after the deal closes next week. How many pork tenderloins can you get in the next week before the sale completes?"

"I can get hundreds, but that would compromise the Army's sides, and I cannot do that. Aside from the Army carcases, I could probably get three, maybe four dozen."

"Will Laurenz be able to supply you that many each week after he takes over?"

"If I offer him a fair price, yes."

"Could he easily increase the quantity?"

"Yes, with timely notice."

Maria's smile expanded dramatically with each exchange. Bethia watched, mesmerised as the smile grew.

"That's brilliant, David," Maria said. "Such a splendid idea. I have my driving papers. Got them for Dada's motorised grape waggon, and Mama has hers too. I love your way of thinking. Brilliant idea."

"I'm lost here," Rachel said. "What have I missed?"

"I'm right beside you." Bethia shook her head. "I'm completely befuddled. The young ones need to explain. David? Maria? Help us out."

David looked at Maria and nodded. She began slowly, then picked up the pace as she talked, "Tante, your Klettgauschinken is sublime. You've told us it never fails to win medals. You should increase production and begin selling it again up and down the valley. Establish some new markets in the Schwarzwald and other new ones across the border in Swiss Schaffhausen. We have the lorry; we can steam it out at the slaughterhouse and repaint it. Mama can design a logo and panel signs... What have I missed, David?"

"Nothing – except to explain that you're a mind reader."

"I'll agree with Maria," said Bethia, "This is a brilliant idea. How long have you two been working on it?"

"A minute for me." David shrugged. "Less than that for Maria."

"This is another example of what I've been attempting to explain to you," Rachel said to Bethia. "It has something to do with emptying our minds rather than rummaging around in the junk that's usually heaped there. Or something like that."

"That's precisely it, Mama." David nodded. "The mind slogging through sludge is the common way of thinking. Ignore the sludge. Think of nothing. When we stop thinking, our minds blossom with creativity."

"Oh, if only I could." Bethia shook her head. "My mind is so full of noise. Scattered things pop out of nowhere all the time. How do you ever get rid of it?"

"We don't. We simply stop paying attention to it. Stop giving it our energy. It starves, shrivels, disappears. It's replaced with limitless possibilities. We can choose to view the emptiness with fear, but I prefer to see it as creative space filled with infinite possibility. From an empty mind, we can create our own destiny rather than replaying the same old patterns and concepts."

"Where have you learned these things?"

"We don't learn such things; they are already part of us. We simply need to uncover them beneath the rubble and sludge of stale ideas and implanted concepts which muddy our minds. Fear of the unknown is the major deterrent. We grasp what's been crammed into our heads as the known, whether it's valid or not. We hang on to it for dear life, afraid to change. Afraid to venture into the unknown, venture into reality. Afraid to truly live."

"Fear of the unknown." Maria nodded. "You've told me that's what most religions thrive on – fear and emotional manipulation. These seem to be the prime enemies to free thinking, to creativity."

"But enough mind stuff," David said, "we need to sense whether the basic premise is valid." He turned to Bethia. "What do you feel, Tante?"

"I love the possibilities – Rachel? What are your thoughts on this?"

"I hadn't thought at all of what I'd do once I got back to Switzerland," Rachel said quietly. "I guess I was leaping into the unknown. Would you like to expand your Klettgauschinken business again? We can start here and then find a place to establish and continue across in Schaffhausen. I would love to help you with it."

"I was doing nearly a hundred a week on my own, besides doing the hams and sausages, while Aaron ran the slaughterhouse. You and I can easily do that many and leave plenty of time for the cellar and the vineyards. I'm excited again. Where do we start?"

"After breakfast, we can walk over to the slaughterhouse," he said. "You can make arrangements for the lorry. Maybe have it steam-cleaned."

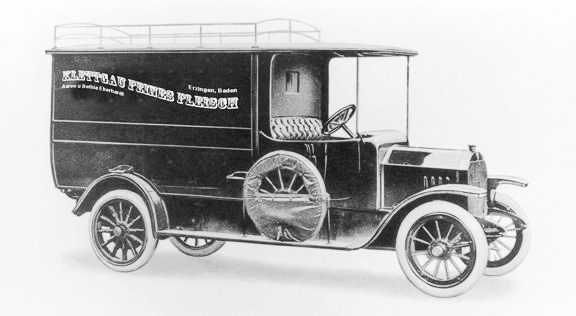

Half an hour later, as they walked into the slaughterhouse courtyard, Bethia pointed across the lot. "That's the new lorry over there, and they'll shortly start loading it for Donaueschingen; it was up in Freiburg and Lahr when you were here on Tuesday, David. It's a Benz-Gaggenau, new last year and it's rated at six tonnes."

She turned and pointed. "But this is my favourite, the Daimler. Two years older, and it takes a quarter the load, but it's far prettier."

"I love these side panels," Rachel said, "But they will have to be changed. I already see designs emerging." She looked inside the open cab, then climbed to the seat. "This will be fun to drive."

"I've never learned it. I'll get Manfred, to give you girls lessons on how this beast works, There's nearly an hour before he heads out."

While Manfred familiarised Maria and Rachel with the lorry, Bethia led David inside to talk with Josef, her manager. "Just follow my lead." She winked at David. "Canada is in the Americas, isn't it?"

She told Josef that she had finally sold the business, and he congratulated her, asking, "Is this the new owner?"

"No, this is David, a grandnephew visiting from America. Amazing what two generations do to the grammar, let alone the accent."

David listened as Bethia gave a quick summary of the sale, explaining that the purchasers, Laurenz and Ursula Großkopf, had contracted to keep the current staff for a year unless some wished to leave. "Our contract also protects the livestock suppliers. As long as everyone continues working as they have worked for us, they should see no change."

"We will miss your friendly hand, Frau Eberhardt. We all will."

"I'll be around. Now, with more time, I'll be increasing my Klettgauschinken production. I need all the pork tenderloins you can spare so I can get started. Then I'd like to slowly move back up to a hundred a week as we rebuild our former market."

"You had a steady market for it before ... You'll quickly win them all back."

"I want to also expand across into Switzerland. Looks like it will be a more stable market into the near future."

"Yes, their neutrality offers a good market for our goods, but they appear reluctant to sell war materials to us. A different definition of neutrality from you Americans." He looked at David. "You sell to both sides."

"Yes, supplying both sides." David clenched his jaw. "I don't know whether it's a matter of trying to appear fair or simply a desire to continue making money regardless of the consequences. Likely the latter; it seems that's what America is founded on."

"Their businesses don't want the war to end," Josef said, "but the rest of us – we wonder why Kaiser Wilhelm doesn't just apologise and stop this nonsense. Stop this madness and send everyone home."

"Your son ...?" Bethia asked hesitantly.

"There's still no word from him. The Army still lists him as a deserter. They've been to our home searching, and they've been here talking with me. From his last letters, I sense it's a living hell in the Belgian trenches."

"Personal accounts picture it as being unbelievably horrid." David shook his head. "Someone has to stop this war."

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top