Part 4B: What is a Story and How Does it Work?

Time and again, reading through perhaps a hundred textbooks and through my personal study, those who seriously consider plot suggest that in any opening sequence a mystery or puzzle is usually produced, one that the protagonist must resolve.

If the author doesn't resolve that puzzle—if the author leaves the ending open and lets the reader "decide," the tale is nearly always unsatisfying. The reader will not be able to relax himself—return to his original state of rest—until he gets an authoritative answer regarding the resolution. In fact, most readers will feel cheated if the question isn't answered. If you watch a murder mystery, you want to know whodunit. If you're reading a romance, you want to know if the protagonists find true love. If you're reading a historical novel, you want to find out the author's version of what really happened.

In fact, if any questions are left unanswered—as to the motivations of characters, how the protagonists tried to resolve the issues, and so on—the reader will be left agitated, and will thus be angry about the story.

Recent studies show that when we are confronted with a mystery and try to resolve it, the brain releases dopamine in order to reward us for the search. As soon as the answer to the mystery is found, the release of dopamine ceases, and serotonin gets released. In other words, we are rewarded in part just for the search, but the biggest reward comes from finding the answer.

So in the opening of every successful story, a mystery or puzzle must be produced, or no story exists at all. Somerset Maugham's little tale about the queen's death doesn't succeed as a story in part because it doesn't create a mystery.

Having said this, I have to consider whether my definition really satisfies you. On the surface, it may sound odd. Why does the story have to answer "Why?"

For example, mysteries are often referred to as "Whodunits," not "Why-dunits." When a dead body is found, the detective immediately sets out to figure out who did it.

But in order to solve the crime, the detective must meet three criteria: he must show the perpetrator's method, his motive, and that he had an opportunity to commit the crime.

Thus, when you find a multimillionaire stabbed in the middle of an airport, you may have ten thousand suspects at first. The detective doesn't need to look far for the method—the guy has a knife sticking out of his back. Nor does he have to consider the question of opportunity. Anyone in the airport has a chance at the victim. Motive becomes the central question in every case.

So a mystery is never finished until the answer to "why?" has been determined. Indeed, if you're reading a mystery and the police have a suspect without a motive, you can be sure that a new suspect will pop up shortly.

In a romance tale, we may believe that most readers are interested in sharing a vicarious love experience. But every romance writer knows that for two characters to be in love, there has to be some attraction. There has to be a reason "why" these two people love one another and get together in the end.

In adventure, it is not enough that the protagonist survive the perils thrown at him. We must answer why. It may be that he's as strong as Conan, has the True Grit of John Wayne, is as clever as MacGyver, or has more gadgets than Agent 007.

It really doesn't matter, so long as the hero has some strength, some unusual talent or determination that illustrates why he prevails.

And yet—my basic definition of a story still isn't complete. Nor is the lion story, for that matter. Something is still bothering you, if you've got a keen sense of story.

The first thing that may be bothering you is this: adequate stakes. Who cares about these people anyway? They should never have let lions in the house. Neither of them at this point really has come alive as a character. Do we feel any sympathy toward these fools? And what about the lions? They seem like the real helpless victims here. Maybe the story should be told from the point of view of one of them.

So as writers we can choose to raise the emotional stakes. We could create sympathy for the lions. Maybe our female character has a favorite, a lioness that she raised from a cub. We can create a scene where we show our female protagonist playing with the big cat, and while she grooms her lioness, it purrs and begins to clean the wife's face in turn, licking her with a huge pink tongue.

We can also raise the stakes for our human characters. We show our heroine as a victim. Her husband is a drug dealer, one who has killed rival drug lords to ensure that he keeps his territory. She didn't know what he would become when she married him. It wasn't until after they married that he began to reveal his cruel streak.

He loves his lions, too—not because they're big cuddly kittens, but because they're feral and dangerous, "Just one skipped meal away from reverting to killers," he likes to say.

So our wife regrets her marriage. Her husband is cruel and abusive. Like a lion, he likes to keep a harem of women. Yeah, she's the one he's married to, but there are plenty of others out in the bush.

And the problem is growing. Perhaps the wife sees her husband as some Manson-esque rogue, spending most of his days on LSD, slipping further and further into his own sadistic fantasy world.

Thus, she has been hoping to escape for weeks. She knows that if she stays much longer, he will kill her.

So she finally has a fight, and gets up the courage to leave. Maybe the husband tries to stop her as she lunges for the door. Maybe he slaps her around, but the wife's "kitten" steps between them, warning him back, giving her just enough time to reach the door.

The wife makes her escape, but more than that has to happen. She needs to recognize that her pet is in danger. It isn't enough for her just to escape; she needs her kitten to come with her.

So she has to try to rescue her pet. She might call a neighbor or try to get her husband on the phone and plead with him. She might ask the police to go check on the cats. Whatever she tries, Algis Budrys, a longtime critic for the Chicago Sun, would tell you that her first two attempts must be futile.

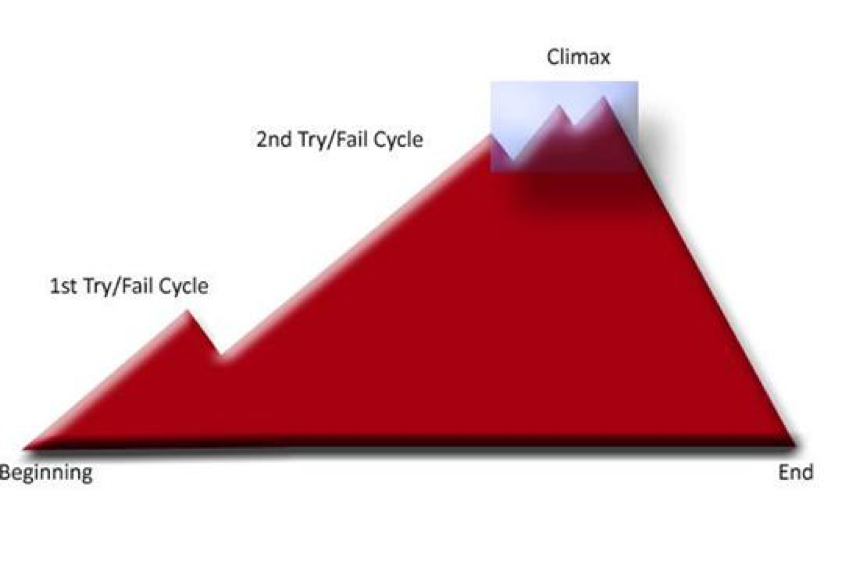

His model of a story contains the following elements:

—The story must have a character

—In a setting

—With a meaningful conflict (some writers would suggest that the conflict be the most vital conflict that that character will face in his or her lifetime). Others would insist that if you care enough about the protagonist, even small conflicts will feel important.

—The character must then try to resolve the conflict and fail.

—The character must try to resolve the conflict a second time, using greater resources—more resolve, more determination, with a better plan, perhaps even calling upon the aid of friends—and fail a second time.

—The character must make one grand final attempt to resolve the problem. (In some cases, this might well be a life-and-death attempt to resolve the story.) The character may succeed in his or her attempt, or may fail. But we must be convinced that the character did everything possible.

—Somewhere, in the end, there must be a sense of validation that comes from outside the character. Perhaps it is another important character who congratulates your protagonist, or some authority—a doctor or a policeman—who looks at the fallen body of the enemy and pronounces the villain dead.

Here is a chart that shows the modified Feralt's Triangle as it now stands.

Now, Algis Budrys didn't invent his definition of a story. It was commonly used by writers in the 1950s. In fact, one large company of agents used to send a similar plot chart and definition to writers in an attempt to teach them how to plot stories.

You will note that I have a blue box at the top of my chart. That blue box represents a reversal. This is an apparent ending—one where the hero suddenly finds himself defeated, but quickly turns the table on the villain and wins the day. Popular movies that feature such reversals include Avatar, Live Free or Die Hard, and Jurassic Park.

The important difference between Feralt's Triangle and the above chart, of course, is that there must be attempts made to resolve a problem, and they must fail. If you read a story where the protagonist succeeds on the first attempt, invariably you will sense that the problem wasn't really that big after all. In other words, it didn't have the heft needed to carry the story. The same is true if only two attempts are needed to succeed. For some reason innate to human chemistry, the hero must attempt to resolve the problem at least three times. Having them try six or seven will most likely be overkill, but even those can work. Remember the movie Groundhog Day?

There are other examples of what one might call "near stories" that don't work, usually because there aren't enough try/fail cycles. Let me give you one, a story told by a friend long ago:

I was in the airport a few weeks ago in Portland, Oregon, and I met a world-famous pianist, Edvard Van Eyck. He was in a terribly foul mood.

It seems that he was supposed to be giving a concert that night, a huge benefit to help AIDS victims in Africa. But a few days earlier, his mother had a bad stroke.

Now, Van Eyck always performs on one of his own pianos, and he had his blue Steinway shipped from Denmark two days before the performance. He got it to the performance centre, but it was raining terribly in Oregon, with 100 percent humidity, and by the time that it reached the hall, his assistant determined that the piano was out of tune.

Van Eyck always insists on tuning his own pianos, but he dared not leave his mother alone for long. Even though she was recovering, he wanted to stay by her side.

But by sheer chance, his assistant made a few phone calls and discovered that they were in luck. Perhaps the world's most renowned piano-maker happened to be in town, hoping to hear the performance. The man, a famous Greek fellow named Gregor Oppornockity, said, "Don't worry about a thing. I will have the piano tuned to perfection."

Of course, in the humidity, the cat-gut strings had stretched and loosened, and Gregor spent several hours tuning the piano, tightening and replacing the strings as needed. He finished late at night.

But only hours before the performance, a huge storm hit, and lightning struck the skylight at the event centre, shattering the glass. Rain fell on the piano, and in a matter of moments all of Gregor's work was undone.

Fortunately, as Van Eyck was flying out of Brooklyn, his assistant was able to call the tuner and beg him to rush back to work on the broken instrument. If he worked quickly, Van Eyck knew, the heaters could be placed on the stage to dry the piano, and the strings could be re-tuned before they needed to be replaced.

It was not until the great Van Eyck landed in Portland that he got the bad news. The headstrong Dane had refused to save the day, and as a result the event was doomed. Van Eyck's assistant told how he had pleaded with Gregor to come save the day, but resisting all pleas and offers, Gregor shouted, "You should know, Oppornockity only tunes once!"

Now, you will notice that the previous narrative has many earmarks of a story. It has a protagonist, a setting, and problem. There is an attempt to resolve the problem—possibly even two attempts.

Then the writer hits you with the joke ending.

This form of story is called a jape, and part of the reason that it lures you in is because you imagine that you are listening to a real, fleshed out story. You expect the narrative to reach a certain kind of conclusion. Instead, it's a joke ending, often with a pun.

Let me suggest a couple of other ways to look at stories that could be helpful in the following section.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top