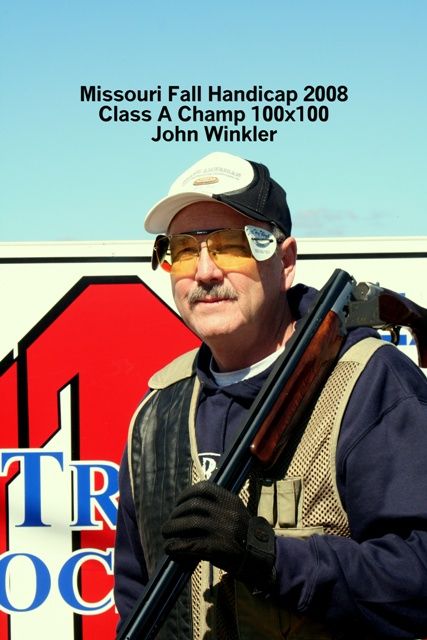

John Winkler

John Winkler at my home in the forest. He'd come to pick me up to go trout fishing. Banner photo: John and I after fishing for crappie at Rothwell Lake in Moberly, Missouri; I'm pictured left.

John and I became friends in our freshman year of high school. We didn't have the same homeroom during elementary school, and in junior high school we just didn't cross paths that much. I met his mother first, in second grade, when John's dog bit me on the leg while playing at recess. I was on the merry-go-round, with a bunch of other students, and the dog was chasing the spinning object with dangling legs. He latched onto my skinny leg and gave it a good chomp, and he wouldn't let go. We had to stop, and the teacher chased the dog away, but its bite infected my leg. John's mother came to class to inspect the wound, and it was a nasty one; the teacher and the mother talked. I wasn't privy to what was said, but I'm sure it was not good for the dog's fate, or for the happiness of John. I never saw the dog on the playground, again. No, it would be years before John and I became buddies.

We would marry the same year, and we would have children a few months apart. When my wife, Beth, was pregnant for the third time, I told John, it's your turn. He said, "Not this time, we figured out what caused it, no more children for us."

John with his bride Vickie on their wedding day. I painted this for Vickie after John's death.

John liked to fish and hunt, and we played cards and board games, and we shot hoops on the outdoor court behind the elementary school building. Me, I love the outdoors and I love to fish, but not as much as a Winkler did. John was a natural marksman, and a natural fisherman. I was a better fisher than a hunter, and deep down I didn't like to kill mammals. I didn't mind shooting birds and eating them, and I ate rabbit and squirrel, but I was a terrible shot. As a fisherman, I could hold my own with most people, but with John, the fish sort of gravitated toward his lure and his bait, and not mine. By 1989 I quit hunting animals all together, but John and I still would fish on occasions. The whole clan of Winkler's were hunters, and every one of them was a marksman. If John would shoot more than he could eat, he would drop it off for people who needed food, and they would thank him as he drove away. My freezer was always full of venison, even though I never hunted deer.

I knew John was the better sportsman, so I listened to him. "Shush, you make too much noise." His eyes were sharp and always on the look for the game, but I was more there as the sidekick. I couldn't hit the wide side of a barn if it were moving. Stand a target still, sure, I could hit it fine, but I never knew how far to lead the animal on the move, and therefore he got most of the game. Goose hunting was fun, not the actual shooting, but the adventure. You'd get up at three or four AM and head out to the blind on the lake, or the river and hunt them. John, always knew where they were. Hunting snow geese was the best adventure of all, come mid-winter. He'd drive until he saw them come off the pond or lake to feed, and we'd wait until they began to ball up. When they're balled up, they'd find their feeding grounds for the day. John always asked for permission to hunt on a farmer's land, we'd stop at the house and ask permission to hunt, you did this because you didn't want to get shot. Usually he got it. Most likely, they knew of him, or thought, here comes that Winkler boy, wanting to hunt. Farmers usually didn't mind us hunting snow geese, as they consider them a pest. Off we'd go, down to the bottoms, and wade knee deep in mud. The geese would see us long before we got to them, but that is expected; they would always return. We just had to get settled in the nearest gully and wait.

By the thousands, the snow geese returned, and they'd streamed toward the feeding grounds for what seemed like forever directly over our head, and landed in the field where we just scared them away. One thing about snow geese is, they have sentries, whose sole job is to look for predators, and we are predators. Any movement by us, any glare of the barrel of the shotgun, and they were gone. It was not a duck in the barrel deal. You'd think thousands of geese directly in front of you would be easy, but no, you had to aim at a particular goose, or none would be hit. As soon as you shoot, they are off. After they were gone, we'd get up and collect the kill and head off, another successful day of goose hunting. I learned how to roast geese, but it was the plucking of the bird; that was the hardest thing to do. Once plucked and the pin feathers removed, it was a matter of getting rid of the wild flavor. Usually, I'd get rid of the taste by rubbing in salt and pepper directly into the flesh, and then either stuffing the bird with apples or onions to remove the gamey taste.

In the northern part of Missouri we have Swan Lake, where people from all over would come to hunt Canada geese. I used to tell John were hunting Canadian geese, and he'd correct me, "We aren't hunting Canadians, we are hunting Canada geese." One year I thought I'd mail in my name for the draw for the opening day of goose hunting season at Swan Lake that was annually issued by the State of Missouri Conservation agency. The odds of winning were next to zero, but I won that year. We'd have to be at the Swan Lake headquarters bright and early, only to go through a lottery to see which party gets what blind, so you never knew what blind you'd get around the large lake. Going to Swan Lake was a yearly thing we did, no matter what. I knew when I went I wouldn't hit anything, but I knew I'd come home with food to eat. John invited his father, and Uncle to hunt with us that opening day, but we drew a water blind, unfortunately. None of us were prepared for a water blind draw, as we didn't bring our decoys. Normally, most of the blinds are dry, but not this year as it was a flooded year around the lake, but we'd hoped to shoot some geese; nonetheless, we came home with one shot, and that shot was made by his uncle.

Another year, John and I were there at a dry blind and it was -7 degrees F, or -21.7c. It was bone chilling. We were standing still in a blind for hours, not moving; just rubbing our hands and telling stories. Across the branch of the lake from our blind was a bald eagle's nest. You could see its white head prominently. This time nothing came our way; however, toward the end of the morning, the bald eagle swooped off its nest and headed toward us; it was just skimming the water. It flew directly over our blind, and its wingspan was as wide as the blind, eight feet. We could almost reach up and touch it; it was the most amazing sight I'd ever encountered in all the days of goose hunting at Swan Lake, perhaps even in all my days of hunting.

An oil painting I did of John hunting geese. John is on both sides of the blind in this painting, because he was so fast to shoot I figured why not feature him as both of the hunters.

Rondeau: This Kind Man

©June 23, 2019, Olan L. Smith

I do believe in death―it's close at hand,

And sound the horn, our gratitude for man,

Repeal a life, make straight the high in court,

For this kind man stood tall by all report;

A sample how a man secures accord

Through passages abode, our heaven's gate.

Alas, we mount the steed, and wait our fate,

Who climbs the mountain's peak by faith is strong,

I do believe in death.

Endures the stress of life, its weight headlong,

Upon a precipice―so, we belong

Not just to man, the Son of Man in state,

No more in fright man thinks what comes is late―

We breathe, exhale our soul, a lifelong song.

I do believe in death.

(A.N. Written honor of my lifelong friend, John H. Winkler, b. 1953 d. June 22, 2019)

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top