Jack the Wiki

The mystery around Jack the Ripper seems to deepen every year. There's new theories and suspects to take into account. There's so called proof and there's complete fabrications.

What draws people so much to a 130 year old legend? What causes a person to dedicate their lives to the myths surrounding him?

Below, you'll find the Wikipedia article exploring the murders of the man they called Jack the Ripper...

-JACK THE RIPPER-

Source: Wikipedia

Jack the Ripper is the best-known name given to an unidentified serial killer generally believed to have been active in the largely impoverished areas in and around the Whitechapel district of London in 1888. The name "Jack the Ripper" originated in a letter written by someone claiming to be the murderer that was disseminated in the media. The letter is widely believed to have been a hoax and may have been written by journalists in an attempt to heighten interest in the story and increase their newspapers' circulation. The killer was called "the Whitechapel Murderer" as well as "Leather Apron" within the crime case files, as well as in contemporary journalistic accounts.

Attacks ascribed to Jack the Ripper typically involved female prostitutes who lived and worked in the slums of the East End of London whose throats were cut prior to abdominal mutilations. The removal of internal organs from at least three of the victims led to proposals that their killer had some anatomical or surgical knowledge. Rumours that the murders were connected intensified in September and October 1888, and letters were received by media outlets and Scotland Yard from a writer or writers purporting to be the murderer. The "From Hell" letter received by George Lusk of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee included half of a preserved human kidney, purportedly taken from one of the victims. The public came increasingly to believe in a single serial killer known as "Jack the Ripper", mainly because of the extraordinarily brutal nature of the murders, and because of media treatment of the events.

Extensive newspaper coverage bestowed widespread and enduring international notoriety on the Ripper, and the legend solidified. A police investigation into a series of eleven brutal killings in Whitechapel up to 1891 was unable to connect all the killings conclusively to the murders of 1888. Five victims - Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly - are known as the "canonical five" and their murders between 31 August and 9 November 1888 are often considered the most likely to be linked. The murders were never solved, and the legends surrounding them became a combination of genuine historical research, folklore, and pseudohistory. The term "ripperology" was coined to describe the study and analysis of the Ripper cases. There are now over one hundred hypotheses about the Ripper's identity, and the murders have inspired many works of fiction.

The Murders

The large number of attacks against women in the East End during this time adds uncertainty to how many victims were killed by the same person. Eleven separate murders, stretching from 3 April 1888 to 13 February 1891, were included in a London Metropolitan Police Service investigation and were known collectively in the police docket as the "Whitechapel murders". Opinions vary as to whether these murders should be linked to the same culprit, but five of the eleven Whitechapel murders, known as the "canonical five", are widely believed to be the work of Jack the Ripper.[10] Most experts point to deep throat slashes, abdominal and genital-area mutilation, removal of internal organs, and progressive facial mutilations as the distinctive features of the Ripper's modus operandi. The first two cases in the Whitechapel murders file, those of Emma Elizabeth Smith and Martha Tabram, are not included in the canonical five.

Smith was robbed and sexually assaulted in Osborn Street, Whitechapel, on 3 April 1888. A blunt object was inserted into her vagina, rupturing her peritoneum. She developed peritonitis and died the following day at London Hospital. She said that she had been attacked by two or three men, one of whom was a teenager. The attack was linked to the later murders by the press, but most authors attribute it to gang violence unrelated to the Ripper case.

Tabram was killed on 7 August 1888; she had suffered 39 stab wounds. The savagery of the murder, the lack of obvious motive, and the closeness of the location (George Yard, Whitechapel) and date to those of the later Ripper murders led police to link them. The attack differs from the canonical murders in that Tabram was stabbed rather than slashed at the throat and abdomen, and many experts do not connect it with the later murders because of the difference in the wound pattern.

The Canonical Five

The canonical five Ripper victims are Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly.

Nichols' body was discovered at about 3:40 a.m. on Friday 31 August 1888 in Buck's Row (now Durward Street), Whitechapel. The throat was severed by two cuts, and the lower part of the abdomen was partly ripped open by a deep, jagged wound. Several other incisions on the abdomen were caused by the same knife.

Chapman's body was discovered at about 6 a.m. on Saturday 8 September 1888 near a doorway in the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street, Spitalfields. As in the case of Mary Ann Nichols, the throat was severed by two cuts. The abdomen was slashed entirely open, and it was later discovered that the uterus had been removed. At the inquest, one witness described seeing Chapman at about 5:30 a.m. with a dark-haired man of "shabby-genteel" appearance.

Stride and Eddowes were killed in the early morning of Sunday 30 September 1888. Stride's body was discovered at about 1 a.m. in Dutfield's Yard, off Berner Street (now Henriques Street) in Whitechapel. The cause of death was one clear-cut incision which severed the main artery on the left side of the neck. The absence of mutilations to the abdomen has led to uncertainty about whether Stride's murder should be attributed to the Ripper or whether he was interrupted during the attack. Witnesses thought that they saw Stride with a man earlier that night but gave differing descriptions: some said that her companion was fair, others dark; some said that he was shabbily dressed, others well-dressed.

Eddowes' body was found in Mitre Square in the City of London, three-quarters of an hour after Stride's. The throat was severed and the abdomen was ripped open by a long, deep, jagged wound. The left kidney and the major part of the uterus had been removed. A local man named Joseph Lawende had passed through the square with two friends shortly before the murder, and he described seeing a fair-haired man of shabby appearance with a woman who may have been Eddowes. His companions were unable to confirm his description. Eddowes' and Stride's murders were later called the "double event". Part of Eddowes' bloodied apron was found at the entrance to a tenement in Goulston Street, Whitechapel. Some writing on the wall above the apron piece became known as the Goulston Street graffito and seemed to implicate a Jew or Jews, but it was unclear whether the graffito was written by the murderer as he dropped the apron piece, or was merely incidental. Such graffiti were commonplace in Whitechapel. Police Commissioner Charles Warren feared that the graffito might spark anti-semitic riots and ordered it washed away before dawn.

Kelly's mutilated and disembowelled body was discovered lying on the bed in the single room where she lived at 13 Miller's Court, off Dorset Street, Spitalfields, at 10:45 a.m. on Friday 9 November 1888. The throat had been severed down to the spine, and the abdomen almost emptied of its organs. The heart was missing.

The canonical five murders were perpetrated at night, on or close to a weekend, either at the end of a month or a week (or so) after. The mutilations became increasingly severe as the series of murders proceeded, except for that of Stride, whose attacker may have been interrupted. Nichols was not missing any organs; Chapman's uterus was taken; Eddowes had her uterus and a kidney removed and her face mutilated; and Kelly's body was eviscerated and her face hacked away, though only her heart was missing from the crime scene.

Historically, the belief that these five crimes were committed by the same man is derived from contemporary documents that link them together to the exclusion of others. In 1894, Sir Melville Macnaghten, Assistant Chief Constable of the Metropolitan Police Service and Head of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), wrote a report that stated: "the Whitechapel murderer had 5 victims - 5 victims only". Similarly, the canonical five victims were linked together in a letter written by police surgeon Thomas Bond to Robert Anderson, head of the London CID, on 10 November 1888. Some researchers have posited that some of the murders were undoubtedly the work of a single killer but an unknown larger number of killers acting independently were responsible for the others. Authors Stewart P. Evans and Donald Rumbelow argue that the canonical five is a "Ripper myth" and that three cases (Nichols, Chapman, and Eddowes) can be definitely linked but there is less certainty over Stride and Kelly. Conversely, others suppose that the six murders between Tabram and Kelly were the work of a single killer. Dr Percy Clark, assistant to the examining pathologist George Bagster Phillips, linked only three of the murders and thought that the others were perpetrated by "weak-minded individual[s] ... induced to emulate the crime". Macnaghten did not join the police force until the year after the murders, and his memorandum contains serious factual errors about possible suspects.

The Legacy

The nature of the murders and of the victims drew attention to the poor living conditions in the East End and galvanised public opinion against the overcrowded, unsanitary slums. In the two decades after the murders, the worst of the slums were cleared and demolished, but the streets and some buildings survive and the legend of the Ripper is still promoted by guided tours of the murder sites. The Ten Bells public house in Commercial Street was frequented by at least one of the victims and was the focus of such tours for many years. In 2015, the Jack the Ripper Museum opened in east London.

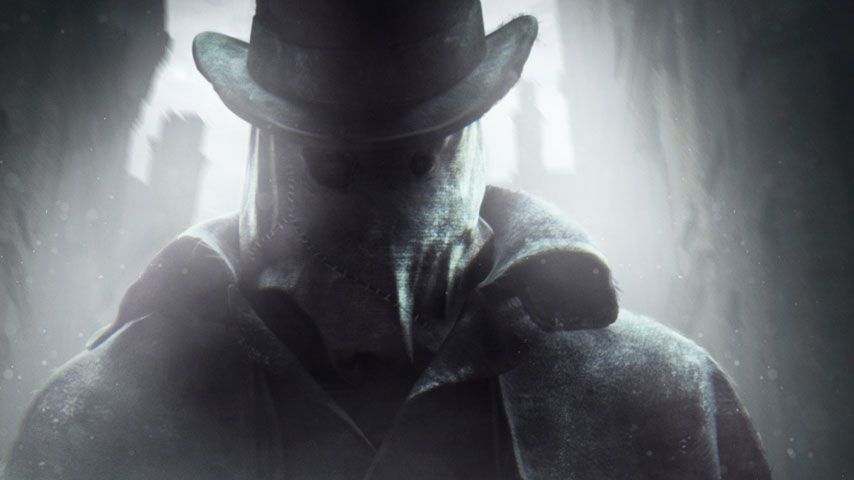

In the immediate aftermath of the murders and later, "Jack the Ripper became the children's bogey man." Depictions were often phantasmic or monstrous. In the 1920s and 1930s, he was depicted in film dressed in everyday clothes as a man with a hidden secret, preying on his unsuspecting victims; atmosphere and evil were suggested through lighting effects and shadowplay. By the 1960s, the Ripper had become "the symbol of a predatory aristocracy", and was more often portrayed in a top hat dressed as a gentleman. The Establishment as a whole became the villain, with the Ripper acting as a manifestation of upper-class exploitation. The image of the Ripper merged with or borrowed symbols from horror stories, such as Dracula's cloak or Victor Frankenstein's organ harvest. The fictional world of the Ripper can fuse with multiple genres, ranging from Sherlock Holmes to Japanese erotic horror.

In addition to the contradictions and unreliability of contemporary accounts, attempts to identify the real killer are hampered by the lack of surviving forensic evidence. DNA analysis on extant letters is inconclusive; the available material has been handled many times and is too contaminated to provide meaningful results. There have been mutually incompatible claims that DNA evidence points conclusively to two different suspects, and the methodology of both has also been criticised.

Jack the Ripper features in hundreds of works of fiction and works which straddle the boundaries between fact and fiction, including the Ripper letters and a hoax Diary of Jack the Ripper. The Ripper appears in novels, short stories, poems, comic books, games, songs, plays, operas, television programmes, and films. More than 100 non-fiction works deal exclusively with the Jack the Ripper murders, making it one of the most written-about true-crime subjects. The term "ripperology" was coined by Colin Wilson in the 1970s to describe the study of the case by professionals and amateurs. The periodicals Ripperana, Ripperologist, and Ripper Notes publish their research.

There is no waxwork figure of Jack the Ripper at Madame Tussauds' Chamber of Horrors, unlike murderers of lesser fame, in accordance with their policy of not modelling persons whose likeness is unknown. He is instead depicted as a shadow. In 2006, BBC History magazine and its readers selected Jack the Ripper as the worst Briton in history.

https://youtu.be/EpOwhXPhPQ8

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top