7. EASY SLEIGHT OF HAND WITH CARDS

The basic plot of many card tricks is a simple one. A chosen card is buried in the deck and the magician, who seems to have no clue as to its name or location, manages, apparently by some extrasensory perception, to find it.

The magician sometimes does this by providing himself with a secret clue — a key or locator card. Here is the method in its simplest form.

1. Secretly get a look at, and remember, the bottom card of the deck. This is your key card.

2. Ask a spectator to cut the deck into two heaps, look at the top card of the lower heap, place it on the upper heap, and then complete the cut. This buries the chosen card in the deck and also places the key card directly on the chosen card.

3. If you now spread the deck, you can run your finger back and forth over the cards and display your mystic psychic powers by stopping at the selected card. Merely look for your key card and touch the first card on its right.

It is best, however, to add a pinch or two of psychological misdirection so that any alert spectator who might try to solve the mystery is stopped before he begins. Here's how.

Always make sure that no one sees you taking a look at the bottom card. Here are three ways to get a glimpse of the card in a natural, unsuspicious manner.

1. Hand the deck out to be shuffled and then keep an eye on it. Many people shuffle in a manner that exposes the bottom card. If this fails, use one of the following methods.

2. When you take the deck again, grasp it with your right hand, thumb on the bottom of the deck, fingers on top. As you bring the deck back and place it in the left hand, tilt it just enough to give you a quick glimpse of the bottom card. If you do this in a casual manner, it will pass unnoticed. The spectators aren't really watching you carefully at this point because the trick hasn't really begun.

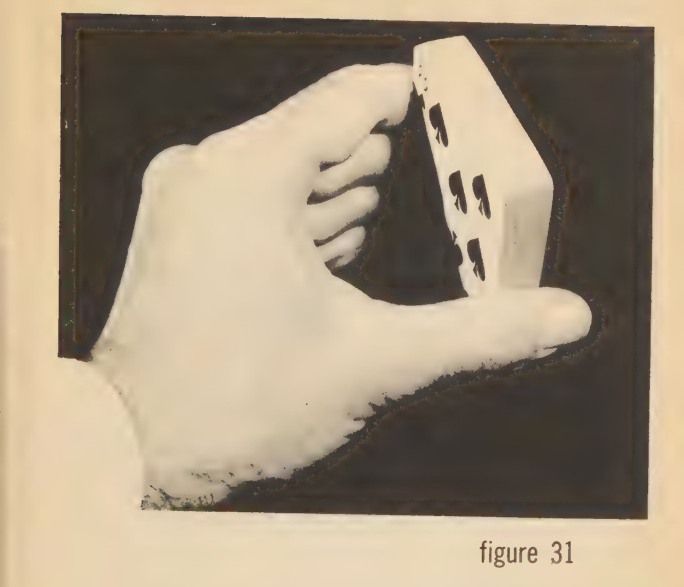

3. You can also wait until the deck is in your left hand, then turn it into a vertical position and tap the lower end of tthe cards against the table to square them up. A quick glance downward as you do this tells you the name of the bottom card because it faces you (fig. 31).

Now, just to make absolutely sure that everyone is quite convinced that you can't possibly know the location of any card in the deck, you should shuffle the cards. You use what appears to be a perfectly legitimate shuffle. Actually, it is not quite perfect and, although the other cards are fairly mixed, the key card never leaves the bottom. You can use either the dovetail or riffle shuffle, which most card players use, or an overhand shuffle. You should be able to do either because some card tricks require one, some the other.

figure 31

1. riffle shuffle in the air

Most card players shuffle by cutting the deck into two halves and riffing them together while the cards are on the table. Many card tricks are performed while you are standing and you should be able to riffle shuffle the deck without resting the cards on a table. If you can't do this, here's how.

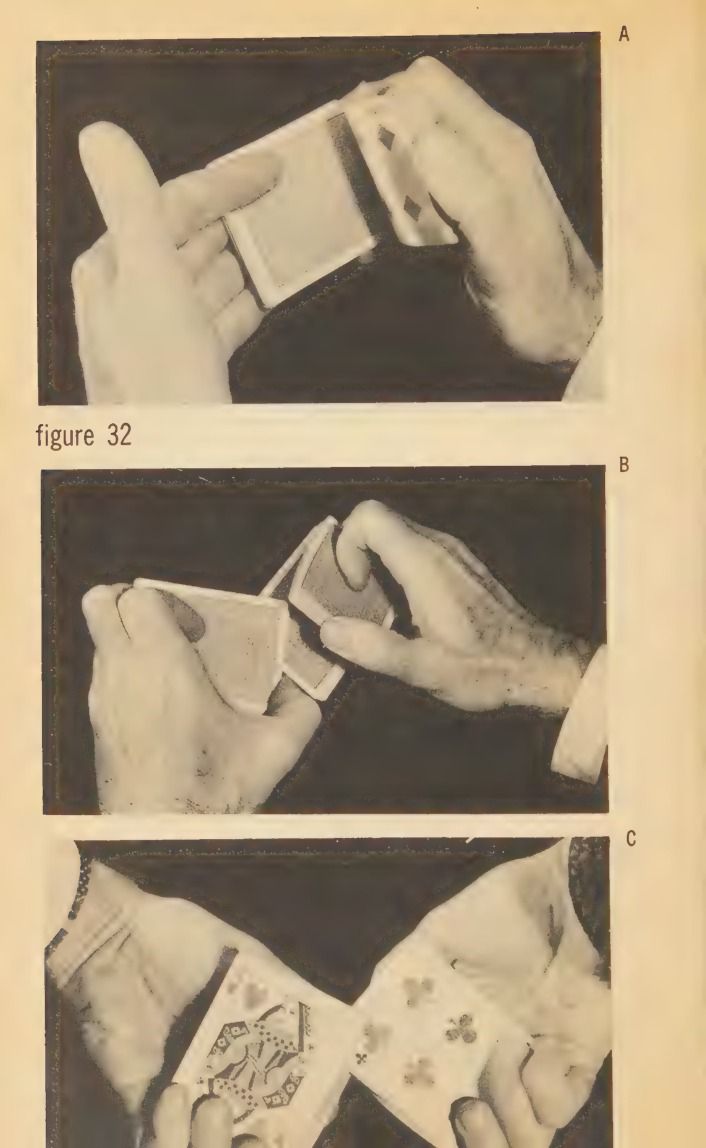

Take the deck in your right hand, thumb at the inner end, fingers at the outer end — except for the forefinger which is curled inward and rests on the top of the deck. Release about half the cards with the thumb, letting their ends fall onto the fingers of your left hand. Then place the left forefinger between the two halves (fig. 32A).

figure 32

Tilt the lower packet up so that your left thumb can take the opposite edge. Each hand now holds its packet in the same way. Riffle the ends of the cards, interlacing them as in fig. 32B. Then push them together. Fig. 32C is a view from below showing how the other fingers grip the ends of tthe cards during the shuffle.

2. false riffle shuffle

Cut the deck into two halves, hold one half in each hand, and riffle the ends of the cards off your thumbs, letting the cards interweave as they fall. Your left hand, which holds the lower portion of the deck, begins rifling before the right hand starts. This allows a few of the bottom cards to fall first, and the key card on the bottom remains on the bottom.

Notice, too, that if the right hand does not let the top few cards fall until after all those in your hand have been released, the top card of the deck also never changes its. position. This, as you will see later, can also be useful.

3. the overhand shuffle

In a legitimate overhand shuffle, the deck is first held in the usual dealing position. Then the right hand comes under the deck and grasps it at the ends, thumb at the inner end, fingers at the outer end. The right hand lifts the deck up, and the left thumb, pressing against the top of the deck, retains one or more cards in the left hand. The right hand moves down again, and the left thumb draws off a few more cards. This up-and-down action is continued until the left thumb has drawn all the cards off into the left hand.

figure 33

4. false overhand shuffle

Here are two ways to retain control of the bottom card during an overhand shuffle.

1. Shuffle until only three or four cards remain in your right hand. Your left thumb then draws cards down one at a time. The last card to fall, your key card, is now on top of the deck. Now shuffle again and draw down one card only in the first movement of the shuffle. This sends the top card back to the bottom.

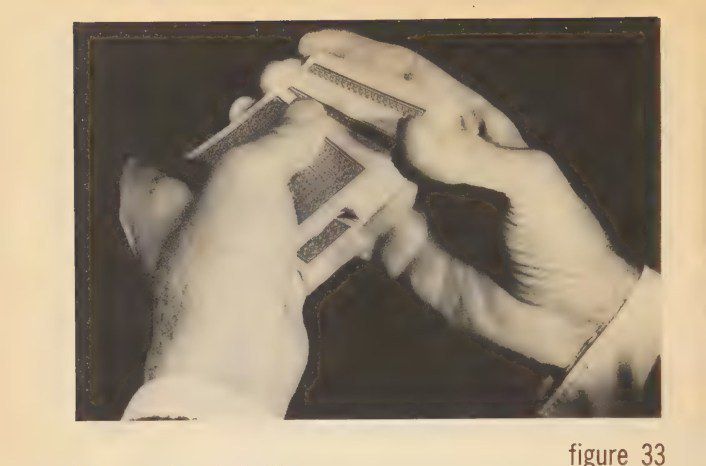

2. In the first movement of the shuffle, as your left thumb draws down one or more of the top cards, your left fingers, under the deck, also press against and draw down the bottom card (fig. 33). Shuffle off the remainder of the deck. The original bottom card is still at the bottom.

Both of these shuffles are thoroughly convincing because you really have shuffled all the cards — except for the one important key card.

As added misdirection, keep your eyes off the deck. If you watch the shuffle the audience will do the same and you will be directing their attention to the wrong place at the wrong time.

5. false cuts

As a final proof that the cards are thoroughly shuffled and that you can't possibly know the location of any of them, follow your shuffle with a cut that looks like the real thing but isn't.

1. Lift off about one-third of the deck and place it on the table. Lift off another third and put it three or four inches to the right. Drop the remaining third between the first two piles. Reassemble the deck by putting the left-hand pile on the center pile, and then the right-hand pile on top of both. Do this carelessly and quickly. It looks fair enough, but the bottom card is still on the bottom.

When you do several card tricks in sequence don't always use the same false cut. Some eagle-eyed spectator might spot it as a phony if he sees it too often. To fool him, do it differently the next time. Here's another method.

2. Cut off the top two-thirds of the deck and place it beneath the cards remaining in your left hand. As you square the deck, insert the flesh at the tip of your left little finger between two portions of the deck — holding a break (fig.34).

Now cut off all the cards above the break and drop them on

figure 34

the table. Cut off half the remaining cards and drop them on the first pile; then follow with the rest. The bottom key card is still at the bottom.

Now let's take the methods for discovering a card outlined at the beginning of this chapter and use it as a basis for several tricks. Note how the shuffling and cutting helps conceal the methods used.

6. the divining knife

A table knife, apparently acting on its own volition, locates a chosen card.

After a spectator has shuffled the deck, glimpse the bottom card using one of the three foregoing methods.

Then shuffle the deck yourself, retaining the key card on the bottom by using one of the false shuffles.

Finally, cut the deck, using one of the false cuts, so that the bottom key card remains on the bottom.

Then have a spectator cut the deck in two heaps, look at the top card of the lower heap, place it on the other heap, and complete the cut. This buries his card somewhere in the center of the deck. Allow the spectator to cut again and then again. This seems to make it impossible for you to know even the chosen card's approximate location. As long as the spectator makes single cuts, his chosen card and your key card will remain together.

Spread the cards in a row, face up. You could finish by simply running your finger back and forth over the cards, and asking the spectator to think Stop when your finger is above his card. You apparently read his mind by stopping on the first card to the right of the key card.

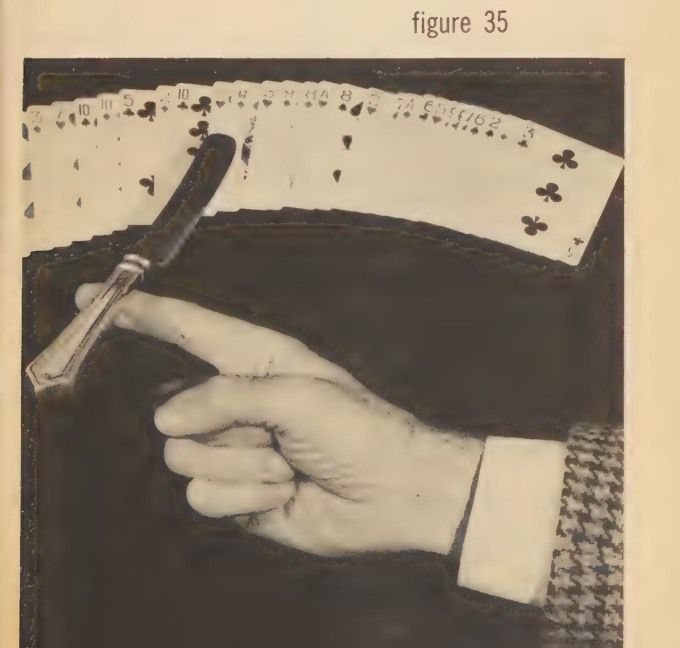

Here's a better climax with more mystery. Take a table knife (or a long pencil), hold it touching the spectator's forehead, and ask him to think of the name of his card. Then balance the knife on the side of your forefinger. Pass it slowly along above the cards. When you come to the chosen card, the knife point swings mysteriously downward and points to the chosen card (fig. 35). You can pretend that this is a demonstration of psychomagnetism.

The knife moves because a very slight, imperceptible, forward twist of your forefinger disturbs its balance.

Presented in this manner the trick will fool even those people who may be aware that a knowledge of the bottom card is sometimes useful.

Having learned this trick, you will find that you are immediately able to perform the next two tricks. They use exactly the same means for finding the chosen card, but, because each trick has a different climax, the spectators will believe them to be different tricks.

figure 35

7. premonition

A psychic hunch from the spirit world locates a chosen card.

Secretly glimpse the bottom card of the deck. Shuffle and cut the deck, retaining this known card on the bottom. Again, a card is selected and buried in the deck. This can be done just as explained in the preceding trick, but there are other ways of putting the key card next to the chosen card. You should vary this procedure now and then so that the spectators conclude that the manner in which the card is selected and returned to the deck is unimportant. They are wrong, of course, which is exactly what you want.

This time, run the cards from hand to hand and allow the spectator to take any one he likes. After he has looked at it, begin shuffling the cards, using the false overhand shuffle. Say, "Return your card whenever you like." As his card comes forward, stop the shuffle and let him replace it on the packet of cards in your left hand.

Your known key card is the bottom card of those you hold in your right hand. Drop all these cards on the chosen one.

This puts the key card just above the chosen one. Another method, even more convincing, is this one. Instead of dropping all the remaining cards onto the chosen cards at once, continue shuffling and, as your left thumb pulls down the next few cards, your left fingers, under the deck, also draw down the bottom card (fig. 33, page 98). Then shuffle off the rest of the cards. This makes it appear that the chosen card must be thoroughly lost among the others.

The chosen card will now, in most cases, be near the center of the deck. Bring it closer to the top by cutting off about one-third of the cards from the top of the deck and placing them on the bottom. This is done so that the dealing of the cards in the next step of the trick won't be too prolonged.

Now for the climax. Begin dealing the cards, one at a time and place them, face up, in an overlapping row. Tell the spectator, "When you see the card tell me to stop — not out loud; just think it." You can, of course, stop on his card since the known key card immediately precedes it. But here is still a more dramatic, more mysterious way to finish.

When your key card appears, stop the deal. "Wait! I've just had a psychic message from the spirit world. It says that the next card I turn over will be yours. Name your card, please." The spectator names his card, you turn over the next card — and that's it.

8. booby trap

The performer offers to repeat the Premonition trick. This time something seems to go wrong; the spectators believe the magician has made a mistake and are just about to tell him so gleefully, when they find that they have been led into a trap.

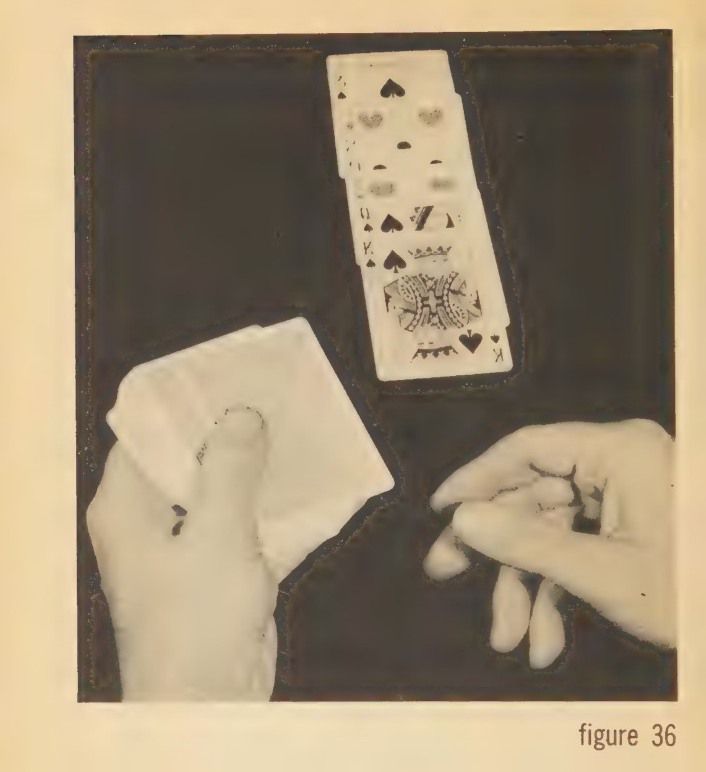

Proceed as in Premonition until the deal. This time don't stop at the key card or the chosen card. Go right past and deal off half a dozen more cards. Then stop and again an-nounce that you have a premonition. "The next card I turn over will be yours." Push the top card of the deck to the right as though you intended to deal it next (fig. 36, page 104).

Then, before some kind soul can exclaim that you've already passed it, add, "My hunches are never wrong. In fact, I'll bet any amount of money that the next card I turn over will be the right one."

Your boasting, self-confident attitude will help convince the spectators that you are about to fail miserably. Someone may even want to make a bet that you're wrong. You can't lose, of course. Instead of turning over the next face-down card on the deck, reach out and turn the chosen card on the table face down!

figure 36

9. the magic spell

A spectator finds his own card by spelling to it.

Secretly note the bottom card of the deck, then shuffle, keeping the remembered card on the bottom. Give the deck to a spectator and say, "Deal as many cards as you like from the top of the deck into a single pile. Stop whenever you get tired. Now, look at the last card you dealt, remember it, and replace it on the pile you dealt. Drop the rest of the deck on top of this pile, then cut the deck." He may cut several times. The key card is now next to the chosen card and cutting, provided single cuts are used, will not separate them.

Take the deck again and ask the spectator to concentrate on the name of his card. "If you concentrate hard enough perhaps I can find it." Turn the deck face up and run through it until you find your key card. The chosen card will be the first one to the right of the key card. Note the chosen card's name and then begin spelling it. Begin the spell on the chosen card and push one card to the right for each letter of the name.

For example, if the card was the Five of Clubs, spell: F-I-V-E O-F C-L-U-B-S. Then note the name of the next card. Suppose it to be the King of Hearts. Begin with that card and spell K-I-N-G O-F H-E-A-R-T-S.

Separate the cards into two groups at this point, gesture toward the spectator with the cards in the right hand, and say, "You aren't trying. I'm getting nothing but static." As your right hand comes back, put the cards it holds under those in your left hand. What you have done is to cut the deck, but if you do it as described, it won't be noticed.

Turn the deck face down again. "Some people just don't broadcast very well." Always blame the spectator. "Maybe you haven't studied that in school yet. Have they taught you to spell? They have? Good. Sometimes you can find a card just by spelling it. Let's take any card as an example. The King of Hearts, for instance." (Here you name the second card you spelled when you were getting set.)

"You spell it and I'll deal." Deal one card off the deck for each letter. And when the S is reached say, "If this magic spell is working, this should be the King of Hearts." (Name the second card ) Show that it is.

"Now you try your card. You take the deck and deal just as I did. If you are a good speller, it should work."

The child, if he can spell, finds his chosen card on the last letter. "Aren't you glad they teach spelling in school? It comes in very handy."

10. A curious prediction

The magician claims to be able to foretell future events and he writes a prediction which comes true.

Ask that the deck be shuffled by a spectator. Insist that it be done thoroughly, and make a point of this so that it will be remembered.

Take the deck after the shuffle and secretly sight the bottom card.

Deal twelve cards in a row face down and ask a spectator to turn any four face up. While this is being done, write the name of the bottom card on a slip of paper, fold it, and give it to someone to hold.

When four of the cards have been turned face up, gather the remaining eight, place them on the bottom of the deck, and then give the deck to a spectator.

Ask him to deal off onto each of the face-up cards enough more face-down cards to bring the total to ten. If there is a seven spot showing he deals three cards onto it. He would deal eight cards onto a two spot, and so on. No additional cards are dealt onto court cards (King, Queen, Jack) because these already have a value of ten.

Finally, have the spectator add the values of the four faceup cards which were chosen at random. A King, three, six and eight, for example, would total twenty-seven. The spectator then deals this number of cards into a separate pile, and turns the last card dealt face up.

The prediction is opened and found to name this last card.

This trick is even more baffling when repeated because the first four cards are different each time.

A word of warning: This works only with a full deck of fifty-two cards.

11. three tricks in one

You can add three tricks to your repertoire all at once by learning this one. It has three different endings.

First, secretly glimpse the bottom card of the deck, then bring it to the top with an overhand shuffle. Ask a spectator- to call out a number and then deal off that many cards, one at a time. This puts the known card at the bottom of the dealt-off heap. Take the top card of the deck and use it to scoop up the dealt cards, so that the known card becomes the second from the bottom.

Give this packet of cards to the spectator. "You count them, too. Never trust a magician." See that he counts them in the same way, one at a time. This again reverses their order and puts the known card second from the top.

Turn your back and give these instructions. "Slide out the bottom card and put it in the center. Do the same with the top card. Turn the next card face up, remember it, show it to everyone, push it in among the others, and then shuffle."

Although this procedure seems fair enough to the spectator, the card he notes is the one you know, and you merely need to disclose it as effectively as possible.

1. While your back is still turned, add this instruction, "Don't under any circumstances forget the name of the card; keep repeating it to yourself: Six of Clubs, Six of Clubs, Six of Clubs." This sudden, unexpected naming of the card he has in mind jolts him and seems to suggest that you have eyes in the back of your head.

2. On another occasion, do the same trick but change the climax. After the spectator looks at the card, tell him to place it in his pocket. Face him and ask which pocket the card is in.

"Tll use my X-ray vision." Look closely at the pocket, shake your head, and say, "All I can see is the back design. Please_turn the card face out in your pocket so that I have half a chance." You don't really need X-ray vision to see this because spectators always put cards in their pockets in this way.

After he has turned the card, look at the pocket again, and pretend that you can see the card. Name the color first, then the suit, and finally the value.

3. After the card is in the spectator's pocket, gather up all the other cards and reassemble the deck. "The simplest way to discover the identity of the card in your pocket is to look at all the remaining cards in the deck and find out which one is missing. The trick is to do it fast — like this."

Face the deck toward yourself, riffle the cards very quickly with your thumb as you watch the faces. Then name the missing card. "It's easy," you add. "Of course, I had to practice ten hours a day for thirty years."

12. he lie detector 1

The performer demonstrates that he can always detect a lie, even while blindfolded.

Once again, your secret weapon is an unsuspected peek at the bottom card of the deck after it has been shuffled. Cut off about two-thirds of the deck and discard it. Give the remaining cards to a spectator, saying "Please cut this packet into two piles, then look at the top card of either pile, remember it, and replace it on either pile."

The freedom of choice you allow here is what convinces him that you have no way of finding his card. But since you already know the name of the bottom card of one pile, you are way ahead of him.

If he replaces his card on the pile whose bottom card you know, ask him to cut that pile, burying his card, then place the other pile on top. This puts the card you know next to his.

If he replaces his card on the other pile, simply ask that the remaining pile be replaced on it. Either way, your card and his come together.

Take the packet and say, "I'll cut the cards several times so that none of us can possibly know where it is." After the last cut, glance at the bottom card. It it should, by chance, be your key card, cut once more so that the chosen card, now on top, will be buried and won't be the first one dealt.

"Some people's faces give them away when they tell a fib, but Ill do this the hard way — without looking." Blindfold yourself with a handkerchief. Tell the spectator that you will show him the cards one at a time, and ask him to name each one aloud. When his card appears, he is to lie and name some other card. "Let's see if you can get away with it."

Warning: Don't let the spectator deal the cards. Since you are blindfolded, he might double-cross you by removing his card and hiding it.

When the spectator calls the name of your key card, you know that the next card is the one he will lie about. As soon as he calls it, whip off your blindfold, point an accusing finger at him, and say, "That's a lie!"

13. The lie detector 2

Children, perhaps because they think they are more experienced prevaricators, often want to match wits with you in "lie detecting" and ask that you do it with them. It is usually best not to repeat the same trick immediately. The first time, the spectators don't know just what is coming and don't know what sort of trickery to watch for, but they have a better chance the second time. You can get around this by repeating what seems to be the same trick if you change the - method a bit, as follows.

This time you get a look at and remember the names of the two cards that lie at the bottom of the deck. The simplest way is to run through the deck, and look for the Joker, saying that this card is a troublemaker. Note the bottom two cards as you do this and also remember their order. Then give the deck a riffle shuffle, letting several of the bottom cards fall first so that the two you have noted remain on the bottom.

Discard the top two-thirds of the deck and give the remainder to a spectator. Ask him to deal these cards out into two piles. "This time I will try to detect two liars at once."

Watch to see on which pile the last card falls. This is the card that was on the bottom of the deck, and the one that was second from the bottom is now the top card of the other pile.

Give these piles to two spectators and ask each one to look at the top card, then shuffle it in among the others. Since you know the names of both cards, detecting lies told about them is a cinch.

Show the cards in the first pile one at a time, and ask the question, "Is this your card?" The first spectator is to reply No each time a card is shown. When you reach his card you tell him that he is lying.

Pick up the second pile of cards, take a look at the faces and, if necessary, cut the packet so that the chosen card will be among the last to be dealt. Tell the second person he may reply either Yes or No and may lie about as many cards as he likes. Each time he says Yes to a wrong card, tell him he is fibbing. If he lies about his own card, catch him on that, too. Under these conditions, he may try to cross you up by telling the truth when he sees his own card. If he does, simply say,

"Well, for once I believe you."

13. The acrobatic cards

The performer commands a card in the center of the deck to turn face up, and it obeys. Then a card chosen by a spectator also turns face up — at the spectator's command.

Spread a shuffled deck of cards face down on a table and ask a spectator to remove one card. When he has done this, pick up the rest of the cards. "I'll turn my back while you look at your card and show it to the others."

While your back is turned, secretly turn the bottom card of the deck face up, note what it is, and leave it face up on the bottom.

Face the spectators again. Hold the deck in your right hand and begin to shuffle the cards overhand into your left hand. Ask the spectator to call Stop. When he does so, have him replace his card on those in your left hand. Then drop all the remaining cards on top and square the deck. The reversed card is now just above the chosen card.

"I have spent years training these cards to obey orders. They are so well educated that they even obey impossible orders. For example, if I command the ——— of ——— (name the face-up card ) to flip over so that it is face up in the deck, it will obey instantly. Watch!" Snap your fingers. "Notice how fast it flipped over? You couldn't see a thing!"

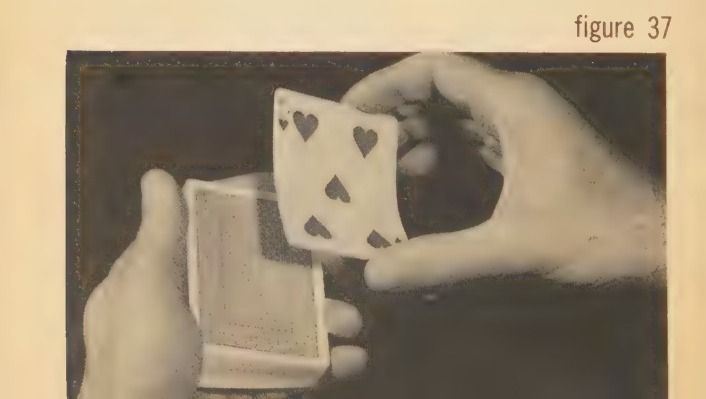

Spread the cards, and show that the card named is face up. Cut off all the cards above the face-up card and place them on the bottom of the deck. Remove the face-up card with your right hand and hold it up, facing the spectators. "You did that very well. Take a bow, please."

While the attention of the spectators is on the "acrobat" card, your left thumb pushes the card now on top of the deck about a half-inch to the right, so that its right edge projects over and covers the left finger tips. Now replace the "acro-bat" card, still face up, on this projecting card.

Cover the deck with the right hand, fingers at the outer edge, thumb at the inner edge, and square the deck in the usual manner, except that the left finger tips push up a bit and keep the top two cards slightly separated from the deck.

As soon as both cards are lined up together, lift them off the deck with the right hand as though they were one card (fig. 37)

Immediately turn the deck over with the left hand and place it face up on the apparently single card. Then cut the deck once. This leaves the spectator's chosen card face up in the center of the deck.

Tell the spectator, "I wonder if your card will obey orders like that? Since I don't know what it is, you will have to do this by yourself." Place the deck in his left hand. "Name your card and order it to turn over when you snap your fingers."

Don't touch the deck again. Have the spectator spread the cards himself. He finds that his card has mysteriously obeyed his command!

figure 37

14. The magic knife

The performer pushes a table knife into the side of a shuffled deck at the precise spot where a spectator's selected card lies.

Run the cards of a shuffled deck from your left to right hand, and ask a spectator to touch one. "We won't even take it out of the deck; just touch one."

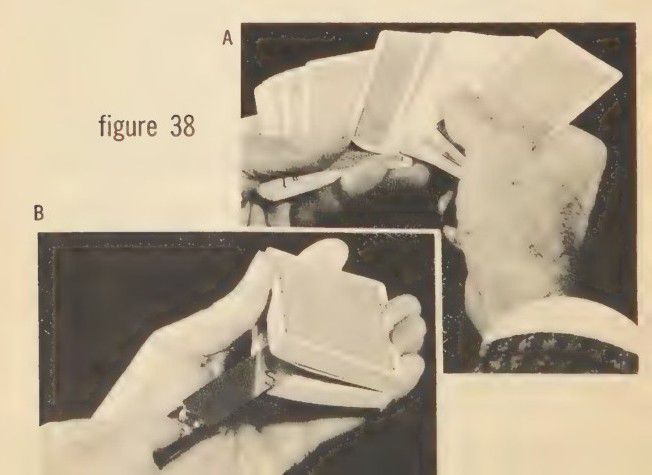

When he has done this, spread the cards at this point, and' tip them up to show the spectator the face of the card he touched. As he notes it, press your left thumb, behind the cards, against the corner of the touched card, and bend it slightly upward (fig. 38A ).

Then push the cards together, square the deck and immediately hand it to someone to shuffle. When you take the deck again, glance at its end and note the position of the card with the bent corner. If it is not visible, turn the deck end for end. If the bent card is close to the top or bottom of tthe deck, cut the deck to bring it nearer the center.

Place the flat side of the blade of a table knife against the spectator's forehead for a moment, and ask him to think of his card. "This," you explain, "charges the knife with thought waves." Rub the knife briskly against your coat sleeve. "This adds a charge of static electricity. That should do the trick."

Push the knife into the deck diagonally, inserting it just below the telltale bent corner. Push the knife all the way in, and place your forefinger on the top of the deck. Then dramatically turn the upper portion of the deck over, showing that you have found the selected card. The knife covers and hides the bent corner.

If you are working in a good light, you can add further mystification. After inserting the knife, press it downward against the corner of the deck. This opens the deck slightly, and you can see a reflection of the corner index of the card in the knife blade (fig. 38B). Ask the spectator if his card was the of (naming it), and then add, "I thought so," as you turn the upper portion of the deck over, showing the card. The fact that you named the card in addition to finding it with the knife doubles the mystery.

15. world's record

A spectator chooses a card and shuffles it into the deck himself. The magician places the deck out of sight in his own pocket, and then finds the card in less than three seconds —and with one hand!

This is another use of the bent corner described above.

You use the same method but the plot is changed so that, from the audience point of view, it is a quite different trick.

Have a card chosen as in the preceding trick. As the spectators look at its face, bend its corner slightly behind the fan of cards, and let someone shuffle the deck.

Take the deck again and say, "It's a strange thing which I

figure 38

can't explain myself, but when I feel lucky I can cut a deck of cards just once and cut directly to any card that is being thought of. Let's try it."

Carefully cut off all the cards that lie above the card with the bent corner. Turn this packet over, exposing the bottom card, scowl at it and say, "Either this is not my lucky day or you people just aren't concentrating." Replace the packet underneath the cards in your left hand.

Lift the next card from the deck, turn it so that only you can see it, and take this opportunity to straighten the corner. Scowl again and put it back on the deck, saying, "No, I missed it completely."

This is, of course, the chosen card, so remember it.

Again cut off some cards, show the face card, and say,

"Wrong again!" Since you now know the name of the chosen card you can, if the exposed card is the same color, add, "It's the right color but everything else is wrong." If it is not the same color you can say disgustedly, "It's not even the same solor. This is bad."

Give the cards a riffle shuffle, keeping the top card on top. "Since I am so unlucky today, there's only one thing I can do to save my reputation as the world's second greatest magician. I'll pass a miracle."

Put the deck in your jacket pocket. "I shall now attempt to beat the world's record and find your card while the deck is out of sight using only one hand and —in less than three seconds!"

Ask the spectators to count to three at the word "Go!" Then go into your pocket quickly and bring out the top card, face down. Ask that the chosen card be named, and then turn up the card you hold very slowly as if you were afraid of more bad luck. Then grin and show that you have finally succeeded.

16. The magic transformation

Card tricks for younger children should be simple and direct. Their favorite is the sudden, magical transformation of one card into another.

Secretly bend the right inner corner of the bottom card of tthe deck slightly downward.

Begin the trick by cutting the deck into three piles. Then ask someone to look at the top card of any pile, and replace it on any pile. If the card is replaced on the pile which has the bent card at its bottom, pick that pile up and cut it, then sandwich it between the other two piles. (This puts the bent key card directly above the chosen card. )

If the card is placed on either of the other two piles, simply pick up the pile containing the bent card, drop it on the chosen card, and put both piles on the remaining one. (This gives the same result. )

Square the deck, cut just below the bent card, and then put it and all the cards above it on the bottom of the deck. (This brings the chosen card to the top.)

Give the deck a riffle shuffle, letting the top card fall last so that it stays on top.

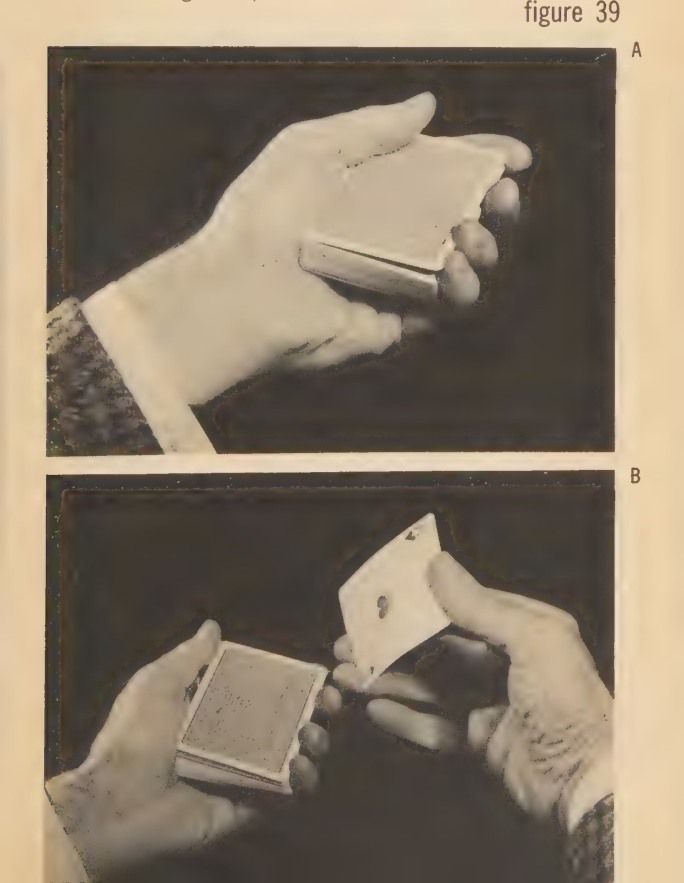

Take this top card off the deck with your right hand, turn it to face yourself, and say, "Your card was not the ——— of ———, was itP" Don't name the card that faces you; call it anything else. As you do this, push the next card on the deck to the right so that it projects slightly.

When the spectator agrees that the card you named is not his, put it back on the deck. Since the second card projects a bit at the side, it is a simple matter to square the deck and retain the tip of the little finger under the second card at the inner right corner (fig. 39A).

Announce that you will make the chosen card jump to the top of the deck simply by snapping your fingers. Snap your fingers, then grasp the top two cards from above, thumb at the inner edge, fingers at the outer edge — and lift both cards off the deck as one (fig. 39B). Press against the ends of the cards, bending them slightly. (This insures that they will remain together. )

figure 39

Show the face of the card to the audience. "There, you see how easy it is." Immediately replace the card(s) on the deck.

When the spectators tell you that the card shown is not the correct one, look surprised, lift off the top card (one only this time), glance at it yourself, and lay it aside, face down.

"That's odd, first time I ever missed. I'll try again." ;

Cut off a group of cards, turn them face up, and show the card on the bottom. "Then this must be your card." They deny this, too.

Replace these cards, cut at another spot, and show another wrong card. By now the small fry, all little sadists at heart, are enjoying your failure. "I think you're pulling my leg. Just what card are you thinking of?"

When they name it, point at the face-down card you laid aside and object, "But that was the first card I showed you!"

Don't turn it up yourself; wait and let them grab for it.

Children always want to see this again so get set for it before they ask. Just as someone turns the face-down card over and everyone's attention is concentrated there, bring your hands together, push the top card of the deck over to one side, and flip it over, face up, on the deck. Square it with the rest of the cards and again insert the flesh at the tip of your little finger under the corner of the card. Keep the deck turned inward so that the reversed card can't be seen.

Retrieve the chosen card, put it face up on the reversed card, square the deck and turn it so that the top card can be seen. "What card did you think this was?" As they answer, grasp both cards along the right side edge between forefinger and thumb and turn them face down as one card. Then, immediately take off the top card with your right hand. Ask a child to blow on it, then turn it over slowly, showing that it has mysteriously changed back again!

17. Mathematical discovery

Another card is chosen and then discovered in a nonsensical manner.

The bent-corner key card is on the bottom at the start. A card is chosen, and returned so that it is below the locator as in the preceding trick. It's the same method, but the story and the climax are quite different.

"Sometimes you don't need magic to find a card; you can do it by mathematics. Like this. You cut the deck three times." Do this as you talk, the last time cutting just below the bent card so that the chosen card is brought to the top.

"Then take the card on top .. ." Lift this off, look at it yourself but don't show it. ".. . multiply it by forty-two, add sixteen, take the square root, and subtract the age of the person who chose the card. How old are you?"

When the spectator gives his age, scratch your head and say slowly, "When I subtract that — my answer is the ——— of ———." (Name the card you hold. )

Pause a moment, then add, "Of course it takes an awful lot of practice to be able to do all those mathematics in your head." On the last word, lay down the card you hold, face up. When they see that this is the chosen card, you get a laugh because it completely exposes your boast that you are a lightning calculator.

18. The power of thought

A chosen card appears at a number selected by the spectator.

Your bent-corner key card is on the bottom at the start.

Any card is chosen and returned to the deck, the locator going on top of it. Cut at the locator, bringing the chosen card to the top, and then riffle shuffle, retaining it there.

Tell the spectator to call out any number between one and twenty, and add, "If you think of that number hard enough your card will appear there."

Suppose he calls "eight." Deal eight cards onto the table, one at a time. Turn up the last card dealt. "Is this your card? No? Then you aren't thinking hard enough."

Put the dealt cards back on the deck. (Because the order of the cards was reversed during the deal, the chosen card is now the eighth card from the top.) Before you count again, cut the deck once, then again, this time at the locator card.

Say, "Try again. Think harder this time." Deal the same number of cards as before. Before you turn up the last card, ask that the chosen card be named. Then show it.

19. Double trouble

The magician tries to outdo himself by finding two chosen cards simultaneously in world-record time. He succeeds in finding one card only, but extricates himself from this predicament by causing the first card to change magically into the second one.

Use two spectators who are not sitting near each other.

We'll call the first one John. Give him the deck to be shuffled, then ask him to call out any number between one and twenty. (You limit him to this so that the necessary dealing is not too protracted. )

Tell him to deal that many cards off the deck, one at a time. When he has done this, take the remainder of the deck and turn your back. Ask John to look at the last card he dealt without letting anyone else see it. While he is doing this, bend the lower right-hand corner of the bottom card downward slightly.

Face John again, drop the deck on his pile of cards. Square the deck and cut it. Then cut a second time just below the locator card which brings it to the bottom and John's card to the top.

Go to a second spectator, Mary, let us say. Ask her also to call a number. This time deal that many cards yourself rather fast. Then tell her, "Just to make sure I did that right, you count them too." See that she counts them in the same way, dealing them one at a time. "Now look at the top card." She sees the same card that John chose.

Replace the rest of the deck on top of her pile, and again cut below the locator, bringing the chosen card to the top. Riffle shuffle, retaining it there.

Now build up the feat you are about to do. "I am going to find both cards simultaneously in less than two seconds — a new world's record! And I'll do it with one hand, with both eyes closed, and while the deck is in my pocket!"

Put the cards in your pocket, roll up your sleeve, and close your eyes. "Ready! Get set! Go!" Plunge your hand into your pocket, grab the top card, and bring it out as fast as you can. Keep the card face down, scow] at it, and say, "That's funny! I only got one card. It's the first time that ever happened."

Go to John and show him the card, but hold it so that Mary can't see it. "Is this your card?" He says it is. "Well, at least the one I did get was right."

Go to Mary. "I'm sorry I didn't get your card. Let's try something else. It might work. Think of your card just as hard as you can and make a magic pass over this one." Then look at the face of the card and shake your head. "No. You didn't think hard enough. Try it again!" Glance at the card again. "That's better! Is this it?" Show it to her without letting John see it. She agrees that that card is hers. Thank her for her expert assistance, return the card to the deck, and proceed with something else.

Most of the spectators will believe the card really did change because it seems so unlikely that both people could have chosen the same card. Even if John or Mary compare notes out loud and everyone realizes that the card didn't actually change, they are still left with the mystery of how two people both happened to choose the same card.

20. Detective story

A card chosen by a spectator plays the part of a criminal.

It escapes into the underworld (the rest of the deck) and is lost by shuffling. The four Kings, playing the parts of lawenforcement officers, are placed in the center of the deck and mysteriously manage to find the wanted man.

Run the cards across from your left to right hand and ask a spectator to touch one. Lift the card he touches, together with all the cards above it, into a vertical position so that he can see the face of the card he chose. "That card is Public Enemy Number One, a notorious bank robber. Remember his name. You are a witness."

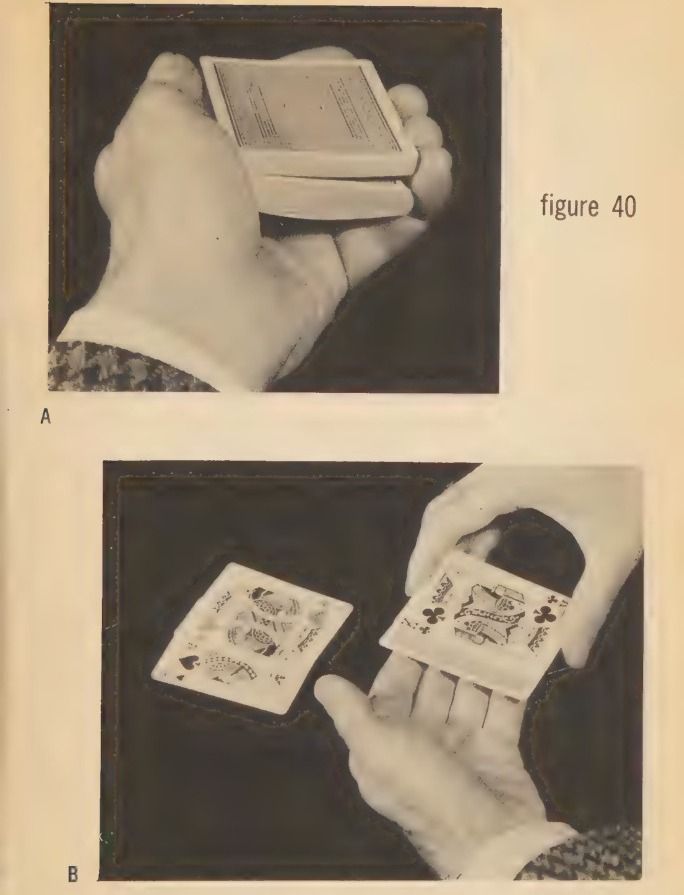

The fingers of your left hand square up the cards they hold and the little finger presses tightly against the inner right corner of the packet. Replace the cards in your right hand on those in your left. Square the deck, but continue to press inward with your left little finger, so that a small opening is maintained in the corner of the deck (fig. 40A, page 125).

Cut off all the cards above the opening and put them on the table. Cut off about half the remaining cards, and place them on the first heap. Then, drop the rest of the deck on top. This triple cut looks fair enough, but it has brought the chosen card to the bottom of the deck.

Pick up the deck with your right hand, and, as you place it in your left, tilt it just enough to get a quick glimpse of the chosen card on the bottom. Then cut the deck again immediately.

"The criminal has made his escape into the underworld and keeps moving around so the police can't find him. You shuffle the underworld so he's completely lost." Give the deck to a spectator to shuffle.

Take the deck again, hold it with the faces toward yourself, and run through the cards until you come to a King.

Take all the cards above the King and cut them to the back of the deck, leaving the King on the face.

Meanwhile, you are saying, "Four of these cards — the Kings — are detectives." Continue running through the cards and as you come to each King pull it out and put it on the face of the deck. Also watch for the chosen criminal card.

When you see it, take it out, just as though it were a King.

Since they are not aware that you cut one King to the face of tthe deck before you started hunting for the Kings, the spectators will assume that the four cards you removed are all Kings.

Spread the top five cards slightly, note the position of the chosen card, then remove the five cards in a bunch. Keep these cards well squared from here on so that no one can see that you have more than four.

Lay the rest of the deck aside. Transfer any Kings that lie behind the chosen card to the face of the packet, so that the chosen card is on the back of the packet.

Now deal off each card singly, showing that you have only four Kings. Like this. Turn your hand so the spectators can see the face card. Your thumb should lie along one edge of the cards, the tips of the other fingers along the opposite edge.

"This King is the Chief of Police." Place your second finger on the King, draw it back toward you, then lift it off, and put it on the table or floor.

Deal the next two Kings off in the same manner, saying,

"This second King is the District Attorney, the third is an FBI man."

Deal the fourth King and the chosen card, which is under it as one card. Simply take them with your first finger at their outer end and your thumb at their inner end, and place them on the cards already dealt. "This last King is the world's bestknown private eye — Sherlock Holmes."

And now, so that everyone is thoroughly convinced that the situation is as you say, you show each King singly once more, but in a slightly different fashion.

Pick up the cards and hold them face down. Push the top card forward, lift it at the outer end, and turn it end-for-end. Square it with the others and name it again. "The Chief of Police." Push it slightly to the right with your thumb and lift it off, taking it at the ends between thumb and second finger. Place it on the table.

Turn the next card over. "The District Attorney." Deal it off in the same way.

Turn the third card face up. "The FBI man." This time you deal two cards as one. This way. Place your right second finger at the outer right-hand corner, your thumb at the inner right corner. As you begin to move the three cards toward the right, the tips of the left fingers underneath press against the bottom card and hold it back (fig. 40B). Your right hand continues moving to the right and carries the top two cards away as one. Place them on the previously dealt Kings.

Turn the last card face up. "Sherlock Holmes." Then place it on the others.

The rest is easy. Ask a spectator to cut off about half of the face-down deck. Put the squared-up Kings face up on the lower half of the deck. The spectator drops his half on top.

"The four detectives go into the underworld and start their manhunt." Riffle the end of the deck. "All the underworld characters are nervous. But it doesn't take four great detectives long to round up a suspect. Look!"

figure 40

Spread the deck out, showing the four face-up Kings with one face-down card between them. "They've arrested somebody. Will our witness now please testify as to the wanted criminals identity?"

He names the chosen card. Turn up the face-down card.

"The case is solved. They got him!"

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top