China Mieville And Plot Structure

To KaranSeraph who may enjoy this.

There is a lot I owe to China Mieville.

Perdido Street Station was perhaps a sort of literary singularity in my life. I read it when I was fourteen-ish, during I phase in my life when I was growing increasingly bored with what modern spec-fic had to offer. This could partially be because I was reading a lot of YA fiction and a lot of fantasy and neither genres are especially noted for diversity (by which I mean diversity in ideas and plot) and original works.

I discovered Mieville, ironically enough from the blog of that venerable ultra-right-wing Voldemort, Vox Day. Apparently, Vox Day's favorite Sci-Fi writer of this generation was a leftist. Not only leftist, he was an all-out socialist. I WTFd pretty hard. Because if a socialist could become Vox Day's favourite write, he had to be one talented socialist.

He bloody well was.

China Mieville is the kind of writer who makes EVERYONE jealous.

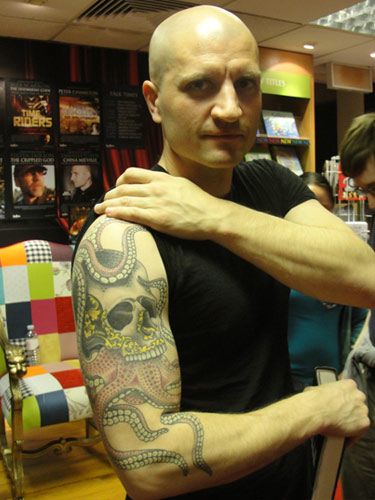

He looks like this:

He writes like this:

"Its substance was known to me. The crawling infinity of colours, the chaos of textures that went into each strand of that eternally complex tapestry...each one resonated under the step of the dancing mad god, vibrating and sending little echoes of bravery, or hunger, or architecture, or argument, or cabbage or murder or concrete across the aether. The weft of starlings' motivations connected to the thick, sticky strand of a young thief's laugh. The fibres stretched taut and glued themselves solidly to a third line, its silk made from the angles of seven flying buttresses to a cathedral roof. The plait disappeared into the enormity of possible spaces.

Every intention, interaction, motivation, every colour, every body, every action and reaction, every piece of physical reality and the thoughts that it engendered, every connection made, every nuanced moment of history and potentiality, every toothache and flagstone, every emotion and birth and banknote, every possible thing ever is woven into that limitless, sprawling web.

It is without beginning or end. It is complex to a degree that humbles the mind. It is a work of such beauty that my soul wept...

..I have danced with the spider. I have cut a caper with the dancing mad god."

And he is the only writer to have one three Arthur C. Clarke awards and he managed it within the span of a decade. And, he's a P.h.D in International Relations.

Yes. 'What the fuck have I done with my life?' is an appropriate question to ask.

Now that I've gotten the obsessive fangirling out of the way, let's get down to what this essay is really about. It's about something very important that I learned from Mieville about how to tell stories. And it isn't what you think. The big lesson China Mieville taught me doesn't relate to prose, themes or ideas. It's all about structure.

He was asked for advice regarding plot structure. This is what he said.

"You're talking about writing a novel, right? I think it's kind of like...do you know , the artist? He was an experimental artist in the 1940s who made these very strange cut up collages and so on and very strange abstract paintings. And I was just seeing an exhibition of his, and one of the things that is really noticeable is he is known for these wild collages, and then interspersing these are these really beautiful, very formally traditional oil paintings, portraits, and landscapes and so on.

And this is that old—I mean it's a bit of a cliché--but the old thing about knowing the rules and being able to obey them before you can break them. Now I think that that is quite useful in terms of structure for novels because one of the things that stops people writing is kind of this panic at the scale of the thing, you know? So I would say, I would encourage anyone that's writing a novel to be as out there as they possibly can. But as a way of getting yourself kick-started, why not go completely traditional?

Think three-act structure, you know. Think rising action at the beginning of the journey and then some sort of cliff-hanger at the end of act one. Continuing up to the end of act two, followed by a big crisis at the end of act three, followed by a little dénouement. Think 30,000 words, 40,000 words, 30,000 words, so what's that, around 100,000 words. Divide that up into 5,000 word chapters so you're going 6/8/6. I realise this sounds incredibly sort of drab, and kind of mechanical. But my feeling is that the more you can kind of formalise and bureaucratise those aspects of things. It actually paradoxically liberates you creatively because you don't need to worry about that stuff.

If you front load that stuff, plant all that out in advance and you know the rough outline of each chapter in advance, then when you come to each day's writing, you're able to go off in all kinds of directions because you know what you have to do in that day. You have to walk this character from this point to this point and you can do that in the strangest way possible. Whereas if you're looking at a blank piece of paper and saying where do you go from here you get kind of frozen. The unwritten novel has a basilisk's stare, and so I would say do it behind your own back by just formally structuring it in that traditional way. And then when you have confidence and you've gained confidence in that, you can play more odder games with it. But it's really not a bad way to get started."

For Bloodistan, the latest project I've embarked on, I decided to try this out. This style of structuring is oddly liberating because it gives you enough content to fill out the ideal word count, it works on a plot basis, leaving very established beats for your audience to follow and it's very easy to get done.

And once that's all done, it is honestly like a huge weight off your back. You can get down to the serious business of writing and ignore all the other shit that gets in the way like your constant fear of getting so much writer's block you run the risk of actually impaling yourself with your laptop. It really simplifies things.

But this whole thing is all about subversions and interesting games writers play with what they have. So what games does Mieville play with structure?

The short answer is, not that many. He plays around a lot with his prose. Embassytown concerns itself with a race of aliens who speak with two mouths at the same time and their speech is printed the way we write fractions. Two words above and below a horizontal line. There's a whole segment in the middle of Railsea about the philosophy of the ampersand. He plays around a lot with ideas and themes. The City & The City is all about borders and cities and the socio-economics of divisions between people. Embassytown is about the philosophy of language and linguistics.

But in all that creativity and playfulness, if you look at the structure behind the stories, you'll notice that they are invariably always the same. And they all tend to follow his own formula he gave above. But there are some things about that formula that strike me as being different from what we usually follow.

For one, 6//8//6 is not really typical for divisions of chapters between the three acts. It usually works a lot more like 3//14//3. The first act is something we have to get over with as quickly as we possibly can. The last act should wrap up quickly enough after the climax. The middle is where the money is.

Mieville rarely works like that. In almost all his books, you'll find very solid, detailed first acts explaining the characters' backstories, motivations and characteristics in great detail before actually putting them in any perilous situations. It is not uncommon to find entire blocks of chapters disrupting the narrative to explore backstories in greater detail (see Iron Council and Embassytown). Even when he doesn't go that far, it takes him very long to get down to the inciting incident for most of his stories.

Where does this come from? Possibly Bronte, who is one of his influences. You can see similar structuring in Jane Eyre where it takes her a terribly long time to get to the house and actually kick the plot into gear.

Why do it? Because characters are the engines that fuel the plot. Readers don't stick around to see just what happens next. They stick around to see what happens next to the individuals who populate your story. Taking time to explain the way they work goes a long way to writing a more entertaining, more impactful story.

So think about that the next time you're plotting your novel. Your characters matter.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top