Chapter 3 | Lust for Glory

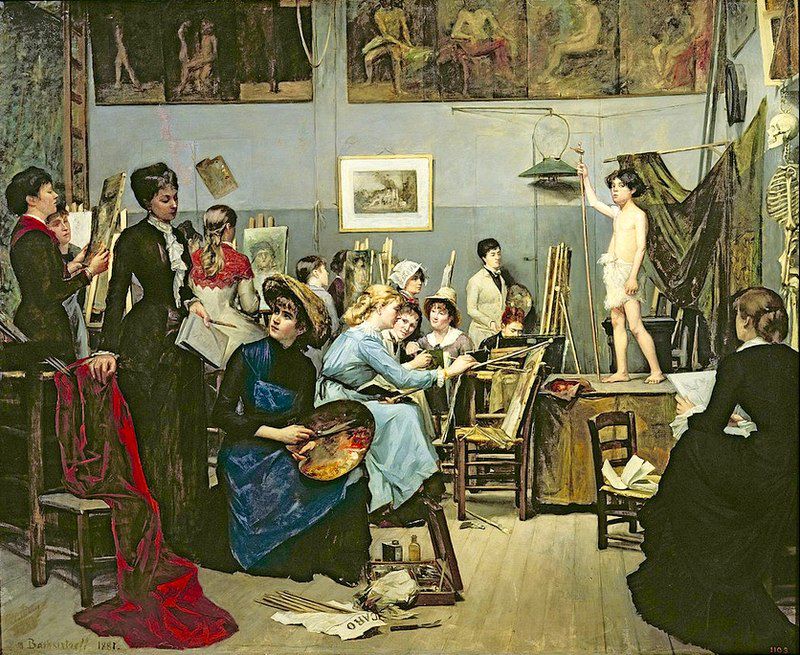

"In the Studio" by Maria Bashkirtseva (1881)

Tuesday, March 11, 1884.

Its raining. But that's not it. I feel ill. Heaven is crushing me. No one loves everything as much as I. Art, music, painting, books, people, dresses, luxury, noise, calm, laughter, sadness, melancholy, jokes, love, cold, sun, all seasons and weathers, the plains of Russia, the mountains around Naples, the snow in winter, the rain of autumn, spring and its follies, tranquil days of summer, and nights brilliant with stars.

I read over the highlighted quotes from my favorite book, Lust for Glory a.k.a. the Journal of Maria Bashkirtseva—a young, ambitious Russian artist who died from tuberculosis at age twenty-five and in addition to her paintings, left her diary as a legacy.

The first time I read it—I'd originally found a copy of it in French at a used bookstore in Munich where we used to live—I cried. To feel the raw ambition of a girl aching to make her name in the world, to print her name into the stars, for her art to transcend her mortality.

I was once what you would call a child prodigy. I'm sure there's still a few of my interviews on the Internet, a spread in a big art magazine with my prepubescent work—paintings that sold for ten times more than what they do now despite being a tenth as good. But my art wasn't enough to hold people's short attention spans. And now here I am, unable to conquer a competition at a measly California Youth Painters fair.

At least my anguish makes for decent material for my diary. One day it will be a valuable chronicle of my artistic process. Historians will publish it for all to read, just like Maria Bashkirtseva's. If my art doesn't speak to people's hearts, my words will. Someday.

Saturday, December 4, 1875.

I was born to be a remarkable woman; it matters little in what way or how. I shall be famous or I will die. Is it possible that God has given me this gloriae cupiditate for nothing? My time will come!

For now, I'm invisible. I'm eighteen and still haven't eclipsed my child prodigy days. Still haven't escaped from the whispers and rumors regarding my father's mistakes. I've fallen off my own pedestal. I'm no one in the picky eyes of history. And any time I dare express myself in a way that's not through a paintbrush? You're too dramatic, Persephone. You're too angry. You're too much.

So I shut up. I realize no one actually cares to know me. And it doesn't matter... because I know what I want. On the outside, I'll put on the mask everyone—teachers, family, art world snobs—want me to wear. I'll be palatable. Reasonable. Polite. I'll be sufficiently nice for people to tolerate me enough to support my work.

Even with my dad. He's always telling me: Calm down, Persephone. And Fitz: Chill out, Persephone. Only my mother understood, her cold exterior a mask for the passion and ambition within her.

And now she's dead.

She's dead and I'm here. In a desert state loaded with superficial people. In a country I don't belong in. Though after moving around so much, I don't belong anywhere, exactly. I belong to nothing but my dreams and my visions. The abstract worlds I paint.

Sunday, February 24, 1878.

I'll go to the studio and I'll prove that one can succeed when one wants to, even when one is desperate, wounded, and furious like me.

▴ ▴ ▴

"Come in," Ms. Montoya says.

I push the door open. The smell of scented candles and the bright colors of the abstract paintings on the walls invade my senses. In front of her cluttered office desk are two chairs, one of which is occupied by none other than Eris Lugo. I stare at the back of her head, the unevenly cut strands of black hair. Her previously relaxed posture stiffens as I walk in, and the room seems to suddenly shrink in size.

I told myself Eris Lugo would not take up more than five minutes of my time. But here I am with her in principal Montoya's office of all places. Have we fought? Have we attempted to stab each other with our paintbrushes? Not this time.

What is she doing here?

With her usual fake excitement, Ms. Montoya says, "Persephone, hello! Take a seat."

I do as I'm told. Eris traces her index finger along the armrest of her chair. "Are you gonna tell me why I'm here now?"

Ignoring her, Montoya asks us how the art fair went, even though she surely already knows.

"I won," Eris says, then jerks her head in my direction. "Pendeja here got second place. Why are we here?"

Montoya clears her throat, ignoring the fact Eris just called me an asshole in Spanish. I suppose since she does it so often, it doesn't even register as a curse word anymore.

"That's... wonderful," Montoya says. "You two, out of everyone there..."

What does she even want me to say? Oh, I had an amazing time staring Eris Lugo in the face again and watching her win with her cheap, overused, unoriginal work?

"Isn't it amazing that you two were also the finalists of the last international Olympiad?" she continues. "For two bright young minds to be here now, in my school—it's such a blessing."

"Oh, it's definitely God's work," Eris says, letting out an obnoxious little laugh. Her gold, diamond-encrusted cross pendant gleams from her neck. As if that weren't enough, she's also wearing little diamond cross earrings as well as multiple golden chains.

Even though I try not to, I still think about it every day—the International Arts Olympiad a.k.a. the Olympics for all things visual art, from sculpting to painting to photography and open to over 150 countries and people of all ages. Four years ago, they hosted it in Moscow. Four years ago, I was supposed to honor Maria Bashkirtseva's memory by showcasing one of my personal classics—an abstract self-portrait comprised of pure geometric shapes. But fourteen-year-old me would never forget the day the $50,000 grand prize went to Eris Lugo instead, a rich brat from San Diego.

I'd never lost anything in my life until that point, and it'd been the rudest awakening yet. The first time I had the misfortune of staring down Eris Lugo's raccoon-like face.

I was in the land of Maria Bashkirtseva and still didn't win. But she would understand what it's like to be looked over while someone else receives the spotlight. I mean, I did win second place and the silver medal, which most would consider the accomplishment of a lifetime, and maybe I would be able to if Eris Lugo hadn't continued her winning streak.

Maybe I would be able to if only a few months later my family and I hadn't moved to the same exact city as her.

Our fathers already knew each other. Iker Lugo, Eris' father, was serving as my father's fine art agent at the time, getting his paintings into galleries and the hands of exclusive, upscale buyers. And my father Marcus, determined to support our family after my mother's death, wanted to move close to him to cash in on as many of those opportunities as possible.

Little did I know, there was more dealing going on than simply art.

"It's been about four years," Montoya says. "The time is coming up again for the next Olympiad."

Another chance at that $50,000 prize. It should be enough to cover most of my father's debt. My father's debt to none other than Iker Lugo. We could finally, finally be free from that family. Money paid off, Eris' winning streak broken—I'm sensing an opportunity here.

"For this year's theme, their idea is to focus on differences and how they can complement each other," Montoya says. "Contrasts." Her eyes trail from me to Eris—who's biting her fingernails now—and back to me. "And what could be more contrasting than the work of two distinct artists?" She pauses to adjust her pink, pointy glasses. "This year, they're asking all participants to work in pairs."

I pause. The balloon of hope within me fizzles out in a sad squeak.

"So that's what this is about?" Erin blurts out. "You want us to work together?" She laughs loudly and motions to me. "Me and her?"

"I know how it sounds, but listen," Montoya begins. "It's extremely important for our school to do well in this competition. Imagine how good it'll make us look." Her eyes shine with the possibility. "And you two are the best chance I—the school has to win. They're doubling the prize money as well. Both winners will get $50,000. $10,000 each for second place, and $5,000 for third."

Everyone at school knows who I am, Persephone Baines the artistic genius whose had her work in galleries before—yes, over six years ago, but it still counts. I'm probably the only thing that gives this lame art magnet school its good reputation. And if anyone knows anything about me, they know about Eris. More importantly, they know how much I would love to send every one of her paintings to some dusty basement in the middle of nowhere for her name to languish in obscurity. Us working together? Please.

"I'm not doing it," Eris says.

"You don't want to win the competition?" Montoya asks.

"Oh, I'm definitely going for gold again. I'm just not working with her. She's crazy."

I narrow my eyes at her, willing my gaze to somehow burn holes through her skin.

Montoya raises an eyebrow. "How so? She's the most talented artist of our times. I hope you know that, Eris."

At least someone appreciates me.

Eris looks me up and down, her poop brown eyes stopping when they meet mine. Not that my eyes aren't also brown, but mine are dark, nearly black in color, similar to the gaping abyss of the underworld, populated only by the screams of its countless damned souls. It suits me. Eris' eye color also suits her, considering that her personality is the literal equivalent of shit.

"Let's see," Eris says, her tone drawn-out and mocking, "she's a control freak. She's got anger issues though she doesn't show it. And what else? She's a narcissistic bitch, but I think that one's obvious. She also has a triangle fetish, since she's so obsessed with using them in her paintings. I don't think we could work together for five minutes before she'd end up sticking her paintbrush in my—"

"I do not have a triangle fetish," I snap, my fists now curled around the edge of my chair.

Eris leans back and crosses her hairy arms over her flat chest. "I'm only worried for my own safety, miss Montoya."

"Your own safety?" I challenge. "You're the one who literally pulled a knife on me two years ago, have you forgotten that?"

Just the fact she carried a knife around in school was enough cause for concern. I remember how paranoid she was acting at that time, her eyes flickering everywhere, constantly looking over her shoulder as if she expected someone to be following.

"Yeah, I already did my time in suspension for that," Eris says.

"It would've been expulsion if it weren't for your dad's bribes," I say. "Isn't that right, miss Montoya?"

Montoya's wide eyes blink at me from behind her glasses. She's guilty. Very, very guilty. She's been receiving bribes from Iker Lugo since Eris got to this school. How else would she get away with selling weed and pills to half our student population?

"Everyone knows she's only still here because of that," I huff.

"Please," Eris says with a yawn. "The real reason I'm still here is because my art is fucking amazing. Even my worst painting is better than all your dumb triangle paintings combined. I've seen your sad tries at realism in AP Art. Haven't you heard about learning the rules before you break them? That's Picasso for you. And you don't even come close."

That's it. I've never physically hurt her before, but there's a first time for everything. If the principal wasn't here I swear...

"She tried to stab me!" I exclaim. "She literally almost stabbed me that time! I would get a restraining order, but my family can't afford the legal fees because her dad—"

Eris shoots me a threatening glare. I know far more about her family's dirty dealings than she's comfortable with. I could ruin her life if I spilled to the right people. But the last thing I want is for them to come for me. So I simply smirk and shut up, happy to dangle her secrets over her.

"I was having a bad day," Eris says lowly. "And you were pissing me off."

"Girls," Montoya says, folding her arms over her desk. "You don't have to work together if you don't want, but consider it. Regardless of all your fighting, I'd like our school to have a place in this competition." She glances at Eris. "The final round is in Mexico City. You'll get the chance to go to a showcase with all the other finalists."

Mexico City? I can't say I'm in the mood to visit Eris' home country anytime soon. It would be far more satisfactory to beat her in her homeland instead of showing up with hands held and pretending to tolerate one another for the sake of the prize.

"As for you, Eris," Montoya says, "I have a special prize. If you and Persephone agree to work together, I will try my best to make sure that you pass all your classes at the end of the year. Now how does that sound?"

Eris picks at a scab on her arm. "Pretty good," she mumbles. I'm thrown off by the sudden change in her voice.

Montoya smiles. "Great. Now, will you two work together?"

I'm not stupid. Her art is derivative trash and makes me want to rinse my eyes with bleach, but she is the second best artist in the school— even if it's only because everyone else is an amateur. It's simple math. You put the best of the best together, and we may both have a chance at gold. Montoya does have a point. And I need that $50,000. Far more than Eris. She has her dad's money as insurance, and we have nothing.

What if this is my path to glory? I can use Eris' technical and realism skills to win, then leave her in the dust. It's clear that all these judges over the years have a bias toward her because of who her father is in the art world, and what if I could use her status to my advantage and come out on top? Could it be that hard?

"Yes," I say after a long silence. "I'll work with her."

Call me a sinner, but here I am making a deal with the devil herself. Not even all of Eris' crosses and Catholic paraphernalia could protect us from how disastrous this could turn out.

"I'll think about it," Eris says after an even longer silence.

"Excellent," Montoya says. "You two can go back to class now."

Eris gets up before I do. She walks out of the office, and I follow her out into the hallway. Once I'm sure no one's watching, I grab her arm.

"Don't touch me," she snaps, prying my hand off. She walks away, but I move in front of her, blocking her movement.

"So what about that competition you told me about yesterday?" I ask.

She looks me up and down as if sizing me up, seeing how much it would take to bring me down in a fight. "I double-checked. It's from ages 8-12 only."

"How tragic."

"Yeah, and you can leave me alone now."

I take a step closer to her. "You use me. You use me when you need someone to mess with and then go back to normal as if nothing's happened. Just like the time you pulled a knife on me."

"Can you, like, stop trying to psychoanalyze me?"

"Tell me I'm wrong."

She puts her hand over her face and groans. "Fucking hell, Ef. No puedo contigo. En serio ya no puedo."

"Don't try to avoid me. What's wrong, Eris? Can't handle the idea of us working together?"

"I have a lot of shit going on right now, and you're pissing me off."

"Oh, are you going to pull a knife on me so you can feel okay for two seconds?"

Now it's she who takes a step closer, pointing her finger at my chest. "You listen up," she threatens. "I know what you were trying to do back there, almost telling miss Montoya about my dad. You know more than you should. And you better keep your mouth shut."

I roll my eyes. "Are you really telling me that she doesn't know your dad launders money for the Mexican mafia? Please."

Eris' jaw juts out in a snarl. "Talking like that will get you killed in some places, pendeja."

"I'm sure you'd love to be my executioner."

I'm not sure what's up with me, but today, I'm the one getting a kick out of messing with her. If I taunt her enough, maybe she'll agree to work with me.

She pulls away, leans against the wall, and runs her hand through her hair, sighing.

"So, are you in?" I ask. "Do you think we could actually do this?"

"Are you giving me a choice?" she mutters.

"Not really. I need that money. That about covers the debt my dad has to pay to yours, right?"

"Why would you wanna use the prize money for that? It's not your responsibility."

Isn't it, though? Because who else will? He's the one who's too depressed to paint or get a job.

"Listen up," Eris says, her posture straightening. "If we're working together, I'm not letting you use the prize money for that shit. Leave it in the past. Whatever happened is over."

"Yeah, tell that to your dad who still expects money just because he saved my dad from prison."

"You should be grateful. You should know that you need me a lot more than I need you in this competition."

"I know," I say, as bitter as the words taste in my mouth. "I don't have daddy's money to bribe the judges for first place every time."

Her face hardens again. "Envy doesn't look cute on you, Ef."

I laugh. "There's very little about you I envy, Eris."

"Yeah, yeah, and you're always hating on me but now you won't get off my ass about this competition."

"If we can agree to keep this strictly business, it may work out."

"Fine," she finally says. "Fine. Because listen up. I want to win this too. This isn't no California Youth Painters shit. The competition's gonna be fierce. No promises, but I'm down to try this out." She motions for me to follow her. "If it doesn't work, it doesn't work. But first, we're going to my house."

▴ ▴ ▴

A/N: Highly recommend reading Maria Bashkirtseva's journal--it inspired a generation of female artists and writers in the 20th century. Reading her words, her testament of her ambition and her longing for something more, was almost as comforting to me as it is to Persephone.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top