Marciana: Looking Back

Upon becoming emperor of the Roman Empire, Caesar Augustus sought to promote traditional Roman values and projected an image of austere frugality. He encouraged marriage and the starting of families and outlawed adultery and in his private life, was said to live in a modest house, sleep on a low bed, and eat common food such as coarse bread. Rome under Augustus had grown fat and rich from the profits of its empire. Those like Augustus believed that the Romans had become too soft and decadent and should return to the austere self-control and rigid morality which had made Rome great in the first place. Around this time, Publius Ovidius Naso, better known as Ovid, caused a sensation with his racy love poetry and pick-up advice which showed a different side of Augustan Rome.

Roman views on sexuality were complex and codified. Sexual preference was not categorized by which genders you performed sex acts with but rather if you were the active or passive participant in these sex acts. Male Roman citizens were encouraged to be sexually prolific as well as sexually dominant over women as well as both their male and their female slaves. Julius Caesar's affair with the King of Bithynia was only considered shameful because he was believed to have been the passive partner, earning him the embarrassing nickname of Queen of Bithynia. Respectable married women, on the other hand, were expected to be chaste, faithful, obedient, and submissive. The Roman views on gender relationship are summed up in the story of the Sabine Women. Lacking women to increase their population, Rome's early settlers raped the young women from a nearby tribe, the Sabines. The Sabine women then submitted to their Roman rapists and agreed to become their wives. A Roman male was entitled to aggressively seek the sexual favors of women and slaves. Some of the advice Ovid gives in his Ars Amatoria (The Art of Love) is more than a little uncomfortable by today's standards:

"And if, after you've kissed her, you fail to take the rest, you don't deserve what you've won. What more did you want to come to the fulfillment of your desires? Oh, shame on you. It was not your modesty, it was your stupid clownishness. You would have hurt her in the struggle, you say? But women like being hurt. What they like to give, they love to be robbed of. Every woman taken by force in a hurricane of passion is transported with delight; nothing you could give her pleases her like that. But when she comes forth scathless from a combat in which she might have been taken by assault, however pleased she may try to look, she is sorry in her heart."

(Ars Amatoria 1:673-78)

The Romans viewed sex as a matter of domination and submission: there were those who penetrated and those who were penetrated (Sayenga.)

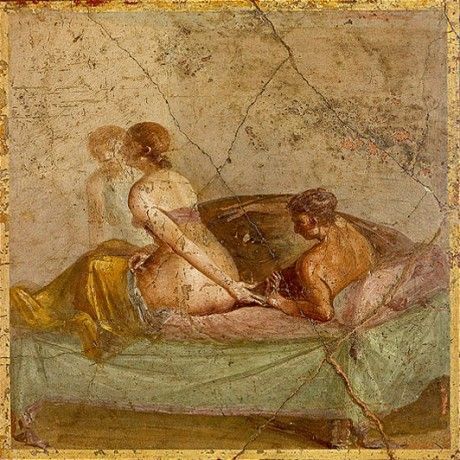

Following its discovery in 1592 and subsequent excavations, the town of Pompeii on the Bay of Naples, a popular vacation spot for Rome's elite, gained a reputation for being a place of decadence and licentiousness due to the graphic depictions of sexual intercourse and phallic imagery, considered a lucky symbol of Rome's masculine power, which can be found throughout its ruins. At least one building, the Lupinar Grande, has been identified as a brothel and thirteen "cellae" or "cribs", small rooms off of street corners where prostitutes plied their trade, have been located ( Sayenga.) Throughout the Roman world, sexually explicit imagery was found even in the most public places, from dining rooms to the changing room at the baths. Sexual imagery had a particular association with baths and dining. Food, sex, and bathing are pleasurable experiences that the Romans liked to link together. The bath attendants, the household servants who waited at table during dinner parties, and the barmaids and waitresses at taverns were usually slaves and therefore available for sexual services. A promiscuous Roman risked catching an STD or STI during their escapades. The bodies found in the cellar at Oplontis, an estate two miles outside of Pompeii which once belonged to Poppaea Sabina, the second wife of Emperor Nero, provide the earliest example of congenital syphilis in Europe (Elston). "Baths, wine, and sex," a Roman saying went, "ruin your body but they're what make life worth living."

Prostitution, which frequently overlapped with slavery, was legal and common. Sex workers plied their trade out in the open at the forum and other public spaces and were subject to taxation. Instead of cracking down on prostitution, Augustus's anti-adultery legislature encouraged it since it diverted men's sexual needs away from respectable women who were not their wives. Roman law defined adultery as sex between two married people who were not married to each other. Sex with a slave or prostitute would not be considered adultery. Even if she enjoyed a close and loving marriage, a Roman wife like Marciana could expect that her husband would pick up a prostitute or take a slave into his bed from time to time. She probably would have been taught to accept it as a fact of married life. If not, divorce was a viable option for a Roman woman stuck in a bad marriage.

The Roman family was centered around the pater familias, the eldest male who had patria potestas, the power of life and death over the people under his power. A woman like Marciana would spend her entire life under the thumb of a husband or father and having an affair of her own was potentially dangerous. Wealthy Roman women often took gladiators (the ultimate Roman heartthrobs) as lovers and some even moonlighted as prostitutes. In his Ars Amatoria, Ovid provides advice for women on how to hide their affairs from their husbands and guardians:

"What's a good guard, with so many theaters in the city, when she's free to gaze at horses paired together, when she sits occupied with the Egyptian heifer's sistrum, and goes where male companions cannot go, when male eyes are banned from Bona Dea's temple, except those she orders to enter? When, with the girls' clothes guarded by a servant at the door,

The baths conceal so many secret joys,

When, however many times she's needed, a friend feigns illness, and however ill she is can leave her bed,

When the false key tells by its name what we should do,

And the door alone doesn't grant the exits you seek?

And the jailor's attention's fuddled with much wine,

Even though the grapes were picked on Spanish hills:

Then there are drugs that bring deep sleep,

And close eyes overcome by Lethe's night:

Or your maid can rightly detain the wretch with lengthy games,

And be associated herself with long delays.

But why use these tortuous ways and minor rules,

When the least gift will buy a guardian?"

(Ars Amatoria 3:634-53)

Extravagant Roman dinner parties were hotbeds of flirtation and seduction with those in attendance casting meaningful glances and subtle signals to their lovers behind the backs of their spouses. A poem from Ovid's Amores describes the awkward situation of being at a dinner party with both his lover and her husband.

"So your husband is coming to this dinner party? I hope he gags on his food. Listen - and learn what you must do. When he settles on his couch to eat, go to him with a straight face. Look modest and lie back beside him. But secretly touch me with your foot. Don't let him drape his arms around your neck, don't rest your gentle head against his chest - don't welcome his fingers to your lap or to your eager nipples. Most of all, no kissing. When dinner is done, your husband will close the bedroom door. But whatever the night shall bring, tell me tomorrow - you refused."

(Amores 1:4)

If her husband was particularly jealous and vindictive, or if she had connections in high places, Ovid's lover would have to be careful not to get caught, lest the consequences be dire.

Julia the Elder, daughter of Caesar Augustus, chafed against her father's restrictions. She was a beautiful, well-educated, and easy going woman who was famous for her wit and free-spirited nature. Though she dutifully married three times to suit Augustus's ambition and bore five children, she took many lovers, so many that people were surprised that her children resembled her second husband, Marcus Vipsanius Marcellus. Julia the Elder retorted that: "I never take on a passenger unless I already have a full cargo." In 1 BCE, when she was thirty-eight, Julia the Elder's scandalous behavior caught up with her. Augustus was fed up with the gossip surrounding Julia the Elder and even considered having her executed. When the crowd plead for Julia the Elder's life, Augustus cursed them that they should have "such daughters and such wives." Julia the Elder was banished to the island of Pandateria (now called Ventotene) in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Ovid wrote Ars Amatoria in 2 CE, the year following the exile of Julia the Elder. The poem was a smash hit but because it promoted adultery and promiscuity, it was seen as subversive to Augustus's moral crusades and a symbol of the louche behavior he sought to discourage. The Ars Amatoria is often cited as a reason why Ovid was exiled to Tomis, a backwater of the Roman Empire on the Black Sea in what is now Romania, in 8 CE. Around the same time that Ovid was sent to Tomis, Julia the Younger, daughter of Julia the Elder, was banished to Tremirus, an archipelago of islands in the Adriatic Sea, under similar circumstances to that of her mother. One of the men she was accused of committing adultery with was Ovid himself. Her husband, Lucius Aemilius Paullus, was put to death following an attempted revolt, a plot which Ovid may have known about. Ovid cryptically described the reasons for his disgrace as "a poem and a mistake." The poem was Ars Amatoria but we can only speculate as to the mistake.

Timeline

27 BCE- Augustus comes to power.

18 BCE- The Julian Marriage Laws forbidding adultery are passed.

1 BCE- Julia the Elder is confined to the island of Pandateria.

2 CE- Ars Amatoria is written.

8 CE- Ovid is banished to Tomis on Black Sea and Julia the Younger is exiled to Tremirus.

40 CE- Caligula imposes a tax on prostitution.

79 CE- the eruption of Mount Vesuvius destroys the city of Pompeii; Pompeii's ruins provide the most revealing look into Roman sexuality.

Works Cited

"Episode One: Order from Chaos." Rome in the First Century. Writ. Margaret Koval. Dir. Lyn Goldfarb. Pro. Patricia Asté. Perf. Sigourney Weaver. PBS, 2001. Web.

Kline, A.S. Ovid: The Art of Love. 2001.

"Pompeii: New Secrets Revealed." Writ & Dir. Paul Elston. Perf. Mary Beard. BBC, 2016. Web.

"Prostitution in Pompeii" Sex in the Ancient World. Writ. & Dir. Kurt Sayenga. Perf. Bill Graves. History Channel, 2009. Web.

"Roman Vice." History Channel. Writ. & Dir. Peter Swain. Pro. Richard Sattin. Perf. Michael Brandon. A&E, 2005. Web.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top