18. Experimentation

1916

"I went over the top of our trench with my unit, with them shooting flares up from behind our line." The lad who had introduced himself as James Davis was staring at his teacup, moving it slowly from side-to-side on the saucer as he spoke. The rest of us seated around the table waited patiently in silence for him to continue.

The soft glow of the lamps and the cosy furnishings in the small parlour would have led me to believe what I was hearing was nothing more than some horror tale, if it hadn't been for the bandages the men were wearing, and the occasion sigh or choked sob. Outside, the freezing drizzle of February kept man and beast indoors and huddled close to their own kind. Large patches of snow dotted the back lawn like a white archipelago in a choppy black sea.

"We overran the enemy trench like we were ordered to. I killed two, maybe three, Germans. I don't remember exactly. They. . . we were the same age, I remember thinking. There was a lot of yelling and, and chaos, and of course, it was dark. That made everything rather unreal. Dreamlike. I didn't think much about what I was doing, I was too..." His voice trailed off.

"Every man here was frightened. There's no shame in saying it aloud when it's true for all," I said, quietly.

James nodded. "I was bloody terrified," he half-laughed.

The other men nodded, and murmured their agreement and encouragement. They all knew exactly what he was talking about, although they, too, shied away from admitting it when it was their turn to speak.

James had been one of four men brave enough to try an experimental idea I'd read about in one of Father's journals. It was the opinion of some doctors at military hospitals around the country that shell-shocked men were not lazy malingerers or cowards attempting to shirk their duty, as was commonly thought, but were suffering from a type of mental-emotional problem brought on by intensive trauma the average Briton could not imagine.

These doctors put forward the idea that the way to treat this new condition was a combination of activity and talking. "The Talking Cure" it was called. British men were too conditioned to keep everything inside, went the line of thinking, and that was what was making them ill. They needed to speak, bring their experiences and feelings out of the darkness of their minds and hearts. That would help them recover from their trauma faster and more effectively. The movement of their bodies would encourage this process of release.

That sounded perfectly sensible to me.

With Cloud Hill, I had the perfect setting for just such an experiment as we were in the country with extensive grounds. I also had fifty injured men at my disposal, none of them with terrible shell-shock, granted, but that didn't matter terribly. What worked well with extreme cases might work fantastically well with mild cases. Or so my theory went.

Could ailing men be cured -- or at least helped -- through such simple, non-chemical means? That was what I wanted to discover.

The military doctor who had been assigned to Cloud Hill, Dr Corriton, had simply shaken his head. "If you want to try it, I can't stop you. But it's nothing more than ridiculous, effeminate mumbo-jumbo, not medicine."

"Many of these ideas are based on the recent theories of Dr. Freud. Do Freud's theories not interest you?"

That had only earned me a scoffing laugh.

"Jews, and especially Jews with with lewd imaginations, don't interest me in the slightest and I'd recommended that they not interest you in the slightest, either. Indulge your silly fantasies if you must, Miss Altringham, but I'll thank you not to ask me to approve of it, or waste my time with it." And off he'd gone, medical coat aflutter.

My four volunteers had spent fifteen minutes in the grand salon gently tossing an inflated, exercise ball to each other as well as they were able.

"Mind the windows, butterfingers!"

"I'm over here, man, not dancing on that table!"

After they'd moved and laughed as much as they could given their injuries, I sat them down in the parlour and asked them to relate in detail how they had been injured. Not any of the "oh, got into a spot of bother " summary, but the full details. If they did not want to speak, they should simply listen to the others.

I also stressed they could express themselves as they pleased; they were not to censor their language simply because a woman was present. That wasn't realistic -- they would certainly have been much more relaxed with a man -- but at least one of them, the tall, lanky lad from Staffordshire, took me at my word.

He had gone second. When he got to the part where he'd been wounded, he stopped speaking for a while. All the joviality had gone out of the group and a few of them fought with tears.

". . . Here in the side. It hurt like fucking hell, sorry Miss, and my tunic was all blood-soaked and I could feel it running all down me, but I had to keep fighting until the retreat signal. Then, when it finally came and we could make a run for it, I slipped in the mud and went right in the barbed wire. I thought I was a goner. Napoo, you know? I didn't think...I didn't think I'd make it back to the trench. I thought I was going to bleed out right there, in no man's land. Started saying my prayers and all. Thought of me mum and little sister. Mates from school. Wondering where they'd put my photograph with the black ribbon on the edge, on the mantlepiece or on the wall."

He stopped talking, but his fingers continued to move the tea cup around.

After each man had had a turn to tell his story, we all got up again and the men tossed the ball around for another fifteen minutes. The second round of exercise wasn't nearly as jovial as the first, and the men filed out of the salon more solemn and pensive than when they had entered.

Three days later, all four of them appeared in the parlour again for another session. I'd been biting my thumbs and wondering if I'd asked them to reveal too much, too soon. The second time, and indeed the rest of the sessions, were similar. Exercise, talking about experiences, exercise.

James was by far the most open and trusting of the group. He was an eager lad who, after an initial reluctance, seemed to blossom into the idea of being able to talk openly about his experiences. He spoke of the weather, the noises, the food, the boredom, the lack of sleep and the fear of constant attack, the fear of writing the wrong thing in a letter home and being admonished as a complainer or coward. The other men would nod, or reference something James had said during their own turns.

"It was just like Davis said. Exactly like."

"Davis said it better than I can and I agree with him. That really is the feeling you get. That's just how I felt, as well."

There were plenty of small physical tasks the men could do, as far as their injuries allowed. I encouraged them to take short walks in the wooded areas and assist Brooks with small repairs around the house and in the Infirmary.

They were also encouraged to write. Small stories, or a poem or simply their thoughts. About anything they felt they wanted to address. Most of it was wretched, of course. Full of misspellings and childlike in approach -- but it was genuine. They were expressing themselves. Bringing out what was locked away in the darkness, and that was the point.

That was as close as I could manage to the conditions Hurst had recommended. All four men seemed to be in better spirits and gain courage from the therapy. None of them was eager to get stuck back in, but they all admitted that they felt they could handle the front better after having participated.

Every so often, I caught a glimpse of Dr. Corriton out of the corner of my eye, standing watching as the men left the house and made their way back through the patches of snow to the Infirmary.

Let him look, I thought. It's working and he knows it.

---------------

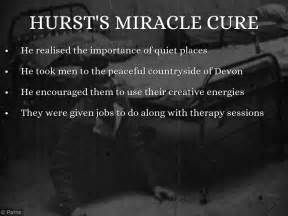

A/N The image at the top shows the four points of Hurst's ideas about treating shell-shock. They are somewhat contested today, but still ground-breaking for the time.

Napoo is a WW1 term. It's the Anglicised version of il n'y en a plus or il n'y a plus , French for 'there is no more'. The British army used it as meaning finished, ruined or dead.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top