Mongolia and the Gobi

Destinations: Mongolia and the Gobi Desert

Trip Dates: 8/7/2015 - 28/7/2015

Tour Operator: Horseback Adventures

All photos taken by us except where stated otherwise.

Where is freedom?

"A traveller once asked me that question," said our Mongolian guide Batka with the usual grin he always had before revealing something to enlighten the tourists who have everything and yet know so little. I had, indeed, gone to Mongolia in search of freedom — the freedom to ride in open spaces, to live unconfined by the high rises and the unnatural rules of the city, to breathe clean, fresh air from the moment I open my eyes to the moment I close them at night, and to cross any boundaries I had, or may have unknowingly, placed upon myself over the years.

I needed that freedom, and I didn't find it in Ulanbataar.

UB, as the locals liked to refer to their capital city, was on its way to becoming just another metropolis. As small as it seemed, and although surrounded by the lush, majestic mountains on all sides, UB had it all — the horrendous traffic, the pollution, the high rises, the evidence of a society driven by profit, status, and selfishness. As impressed as I was at how modernized it had become in just a few decades after the country had regained its independence, I had wanted to leave Ulanbataar the moment I set foot in it, hoping — praying — that behind these concrete walls, would be the life-altering motherland of Chinggis Khan that I had come to see. Ulanbataar was a sad reminder — a strong evidence — that the majority of people anywhere, of any race, culture, or color, are willing to give up freedom, and perhaps also pride, for the sake of comfort. It wasn't wrong, especially for Mongolia whose lands and weather are considered among the most unforgiving our planet has to offer. It was simply sad to think that one day, there would truly be no place left on earth where people still know how to live in harmony with nature, where self-respect, honor, and kindness are still regarded higher than money and status, not even in Mongolia.

But I had always travelled to foreign lands to be proven wrong, most of the time by humanity or my own expectation, for better or worse. Traveling holds little meaning without its imperfections or when it simply meets your expectation. Just a little over an hour of flying from UB to Moron on our way to the famous Khovsgol lake, I knew from the grin on my husband's face when he returned from the car that I hadn't picked the wrong place to spend the next twenty days of my life. "We have a classic car," he said.

And there it was, surrounded by a fleet of state-of-the-art SUVs, the strange-looking minivan so serious and grey I could imagine my great grandfather behind the wheel. "It's a Russian military vehicle," Batka told us with an overly proud grin, and I knew then, that we had the right guide who knew exactly how to show off his country the way we wished we would be shown. I was ready for the ride, and I only hoped that the young couple we would be traveling with for the next three weeks would feel the same. "They wouldn't have picked Mongolia if they didn't want this," was my wishful thinking, having placed my finger on it as my next self-torture expedition just to see if I had what it took to survive the most rugged trip of my life, armed with no modern comforts save for a headlamp and a bottle of bug spray. What I hadn't found out until much later, was that this sweet, adorable couple had picked Mongolia for their hard-earned, long-awaited honeymoon. I would have skinned my husband alive for the Mongolian toilet alone, but that is another story for another time.

One of the real shame about Mongolia has to be the fact that 99% of the country screams at you to get behind your own wheel and simply find your own track to explore, and at the same time it would be an act of suicide in every sense of the word for the same percentage of the tourist population on earth to attempt such thing unless you have an experienced Mongolian driver in the car with you. It's pleasantly unfortunate, like most things here, that Highways exist in Mongolia in the same rarity as western toilets. To put it in perspective, of the 1.5 million square kilometer area, Mongolia has just 1,500 kilometers of paved roads. What this means is that the rest of the roads you see on any map of Mongolia are what can only be described as semi-permanent tire tracks, which are not to be confused with the tire tracks your fellow Mongolian driver left behind last night when he went off-road to visit his cousin's ger along the way, or the one your own driver made when you ask him to stop for a toilet-less toilet break this morning. The only way you can identify which tire tracks to follow if you don't already know by experience is to stop for direction, given that you can find one living soul of your own specie within a 10km radius, and that you speak Mongolian pretty well. That said, you will still need to ask for direction when the tire track happens to split three ways again about every few kilometers or so. The closest thing to a landmark here are the herds of goat or yak and a few gers along the way, both of which move throughout the year so google maps wouldn't work either, I'm sorry to say.

Apart from the high probability of being lost in the country that came 6th place in the world's lowest population density ranking, one also needs to account for the possibilities of running out of gas, into rocks or engine problems, of being stuck in the mud when it rains, or in the flood when that same rain refuses to shut off for the fifth day. Add to this the feeling of being thrown into a jar and shaken vigorously for three to eight hours at a time and you will come close to understanding what a road trip in Mongolia feels like. Mongolia is a huge country, and the first lesson you will have to swallow when you begin your journey here is how very small, insignificant, and powerless you are against nature, and it makes little difference whether you're in an expensive or an old car. There is no pain-free, modern way to travel Mongolia and trying to do so is missing the point of why you may want to come here in the first place. This is a country born on horseback, and the only reliable, comfortable, and convenient way to see Mongolia that makes the most sense is, I'm most delighted to say, on a horse.

For riders, the landscape of Mongolia is like Disneyland to a six-year old, a triple beef burger to a meat lover, a full-fat cheesecake with whipped cream on top for girls on a diet. This is it, the Mecca of horseback riding you thought you could only dream of, and in your dreams the flat plains you wished you could gallop upon forever will still be dwarfed by the epic steppes of Mongolia. Everywhere you look is a perfect place to ride, and it didn't help that there were horses roaming free along the road, in the wild, everywhere for every few kilometers you travel. This is the land where horse population outnumbers human's, where it's not uncommon to spot horses in three-digit numbers within half an hour. If you love and breathehorses, you will have to see Mongolia at least once before you die. Horses here are the most essential means of transportation and the center of the universe for the nomads. The saying that "A Mongolian without a horse is a bird without wings" is an understatement of the century.

"Horseback riding here is different," our guide told us on the first day of briefing, "For one thing, the horses are half wild." I looked around at my three companions who were all beginners, wondering if they were all perceiving this to be as much of a joke as I did. "Someone will catch your horses from the mountain and bring them down in the morning." It surely wasn't the answer I was expecting when I asked him to explain 'half wild.'

Mongolians won't just make you feel incompetent on a horse, they will also tell you that your riding style doesn't work whether you ride Western or English. The nomads ride with painfully short stirrups, with heels up, and on cushion-less wooden saddle. The word for go is "Chu" and, alas, there are no words for stop. They sit on an angle, alternating from left to right periodically to keep themselves comfortable. It broke every rule of horseback riding I had ever been taught, and yet there are few things that could beat the beauty of watching a Mongolian on horseback. I don't think they would ever understand why we need to go to such lengths to ride correctly. Horsemanship here is being able to control your horse in any situation and virtually live on it for days at a time.

Which was probably why our guides were making bets on how long I could possibly continue to ride in such ridiculous positions during my first canter on the steppe. Try the proper English rising trot here and Mongolians would beg you to stop for the reason that it makes them feel exhausted just watching you. "You'll be tired before your horse riding, like that," Batka laughed. For one thing, I didn't know I was supposed to be able to ride until my horse quits on me, for another, after having close to a hundred lessons in two continents, two riding styles, and under three different trainers, I had never been taught otherwise. But do you want to mess with people who can pick flowers and sticks from the ground, run down a wild horse hands-free, and take selfies to update Facebook status while galloping on a horse? You do not. You learn from them.

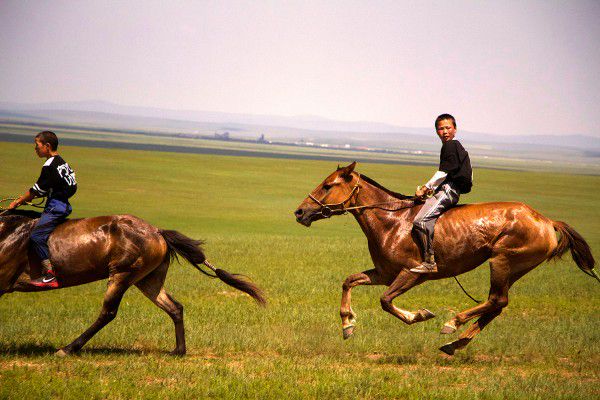

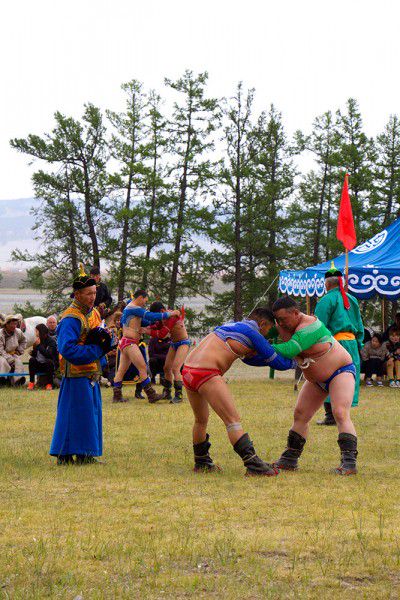

But Mongolians won't teach you how to ride, for the reason that they have no idea how. "My brother put me on a horse without a saddle and told me come back on it or I'd shame the entire family," Batka said, "That was how I learned to ride as a kid." It was the traditional Nomad horseback riding lesson — throw you on a horse and see what happens. There are no rules here, no riding style you have to conform to and watching the horse races at Nadaam where every rider rides differently will confirm the statement. This is nomad country where freedom is found in everything you do. You're free to ride the way you want, as long as you want, wherever you want given that you're aware that you can die from it. The freedom to abuse yourself is also yours. So don't count on anyone stopping you if you insist.

Surprisingly, the throw-you-on-a-horse-and-see-what-happens technique works. The couple we were traveling with had gone from zero experience to galloping at 50 km/h in three days when it would have taken an average beginner at least a year elsewhere. The only instructions Batka had given us were to stand, squeeze, and hold on to your life. Yes, stand, as in creating an A-shape figure over your horse where your bottom rarely touches the saddle while you trot, canter, or gallop. The technique was so simple (even though it requires that you possess thighs of steel), and yet so practical it left me wondering why we ever endured bumping on the saddle in the first place. I learned all I could the lessons that would change how I want to ride for the rest of my life. No joy had ever come close to standing on the stirrups to canter or gallop on horseback. No saddle I'd ever been on, English or Western, was as comfortable as the home-made-looking Russian military saddle we used. I was on and off six horses for two weeks, and hundreds of kilometers later, I returned with a whole new level of confidence on horseback, and memories of the best rides of my life far beyond what I had expected to come home with.

It was during Nadaam festival week and the longest and busiest national holiday of the year, when every Mongolian seems to be taking a road trip somewhere. Three days after we'd arrived, it began to rain, and for almost two weeks it didn't stop. Small rivers and lakes formed everywhere on the steppes, cutting through roads and damaging parts of the highway. I don't know anyone at home without a proper SUV that would even try to drive in that condition, but here, people just keep on going for their holiday despite the road condition and the weather. By the third day of rain I had seen too many cars in trouble than I'd ever seen in a lifetime, from being stuck in the mud, running out of gas, breaking the engine driving over rocks, to being half-submerged in under 10 degrees water on the way that leads to the most touristic place in the country no less. It was only because of our Russian Military vehicle and our award-winning driver, Boogi, that we'd survived the road. This, after all, was Mongolia, one of the hardest, coldest, and cruelest country in the world to travel, and we had already picked the easiest season to do so.

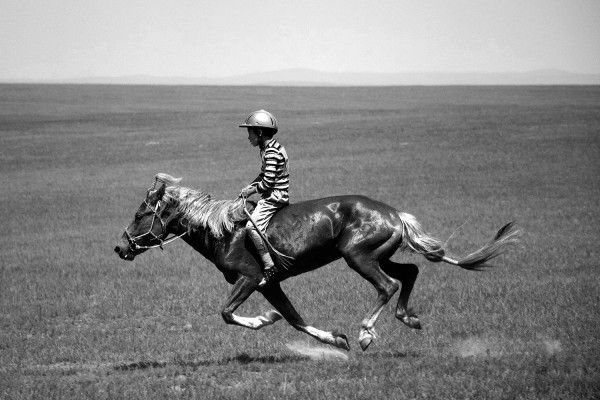

Nadaam horse race. No helmets, no saddle. This is the highlight of all the races: the children.

By the end of three weeks I had gotten used to living among nomad families, and gained a new level of self-respect no amount of money or social status had ever come close to providing. I finally understood why, with no permanent home, no land, and only the most basic personal belongings, the nomads stand a lot taller and lived a lot prouder than most people I see in the city. Mongolian hospitality is spotless, and yet you will never have to be reminded that these are the people of Chinggis Khan. They are extremely proud of their heritage, their tradition, and their land. They do not beg, no matter how little they have, and merchants will not go out of their ways (or even their seat) to get you to buy something. It was a rare privilege to have been among people who lack even the most basic necessities in life, but never find their life lacking in any way. Coming from a society where people feel ashamed for losing jobs or not getting into a reputable college, it was a much needed revelation of what life should be, and how depressingly wrong our modern society is today. Success is being able to say that you don't need anything else, and do we really need anything else but food, shelter, and a loving family? Happiness is a choice. Life in the steppes have taught me that very important lesson. Sitting by the fire that would burn out in an hour, knowing that it would soon be too cold for me to sleep through the night, that I'd wake up hungry when the only food available is the one I'd have to force myself to swallow to stay alive, I looked at our host who lived like this everyday and came to the realization that it is always a waste of time and energy to think of how much you're suffering and feel sorry for yourself. Mongolians take pride in being able to survive with what they have, not in getting what they don't. To always find happiness, you simply have to Mongolize yourself in every situation. You do what you can, and take pride in finding courage to not give up when life gets hard. There are many great things to see in Mongolia, but if you skip the chance to live among the nomads for the comfort of ger camps, you will only see Mongolia, but never truly experience Mongolia.

We covered over 2,000 kilometers by land in 21 days, starting from the lush, green forest of the north and its impossibly clear blue lake, through the majestic steppes of central Mongolia, and ending our journey in the stony desolation of Gobi. I will say, that Mongolia doesn't quite possess the most beautiful landscape I have seen, and if you come seeking for paradise outside of horseback riding, you may be disappointed. The true beauty of Mongolia that sets it apart from everywhere else in the world is the unparalleled experience of being here. It's the picnic by an empty lake watching the herds of yak and goat passing by. It's standing in the middle of an endless grassland feeling dwarfed by the epic size of the steppes, surrounded 360 degrees by choices of where to go. It's the wind on your face as you gallop on the plain full of wild flowers in rainbow colors that stretched to the horizon. Most of all, it's knowing your own limits and breaking them as you step out of your comfort zone and embrace whatever life throws at you. When you're no longer confined by your own fear of suffering, you will find what you've been looking for all your life.

Where indeed is freedom? Ask any Mongolian and they'll tell you.

Freedom is in Mongolia.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: AzTruyen.Top